Lucy Rorke-Adams, MD: Trailblazer, Pediatric Neuropathologist, and Would-Be Opera Singer

Lucy Rorke-Adams, MD: Trailblazer, Pediatric Neuropathologist, and Would-Be Opera Singer

Friend of the University of Rochester’s Flaum Eye Institute delves into her legendary career, philanthropic interests, and passion for advancing the human condition.

As a young girl, Lucy Rorke-Adams, MD, a child of Armenian immigrants, thought that someday she’d become an opera singer. But, a missed audition with a Metropolitan Opera singer as a teenager set her on a different course, leading her instead to an illustrious 58-year medical career as a pediatric neuropathologist.

Her career highlights include becoming the first woman president of the medical staff at the Philadelphia General Hospital and later at The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, where she spent most of her career. She was also chair of the Department of Pathology at both institutions and acting CEO of Children’s for 18 months. She held long associations with the Philadelphia Medical Examiner’s Office, the Wistar Institute, and Wyeth Research Laboratories. She was also a professor of pathology, neurology, and pediatrics at the University of Pennsylvania’s Perelman School of Medicine.

Later in life, Rorke-Adams even became one of the trusted keepers of Albert Einstein’s brain.

Family life

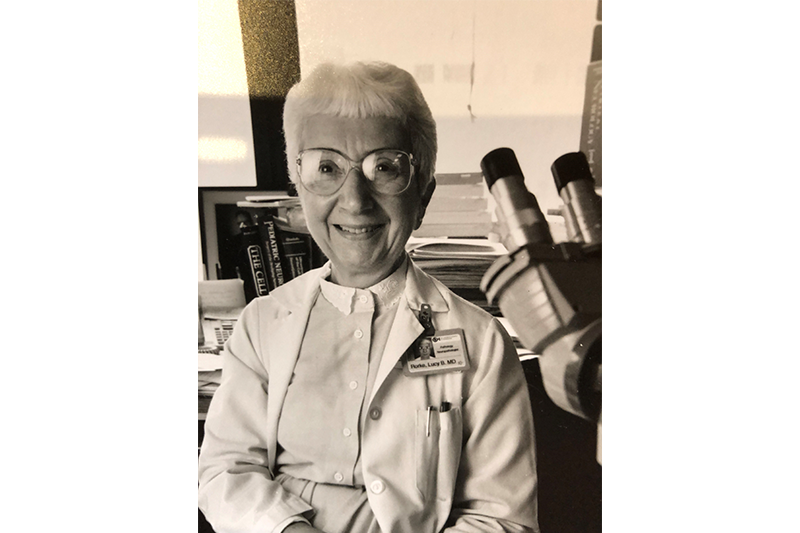

Dr. Lucy Rorke-Adams

“I grew up in St. Paul, Minnesota. My parents were immigrants. My mother was a survivor of the Turkish massacre of the Armenians during the First World War. My father had emigrated to the U.S. in 1913 as he had been warned of the impending massacre. As a child, I often heard the story of how, when the Turks came to my grandparent’s home, they shot and killed my grandfather and disposed of his body by casting it into the Black Sea. My grandmother, my mother, and her four siblings were separated from each other. The Turkish plan was to deport them to a desert, a long distance away. Those who did not die en route would perish in the desert.

Before leaving home the following day, my mother decided to take with her scissors, a tape measure, and a thimble. She wasn’t sure why—something compelled her to do so. While the group of deportees were resting in a marketplace in the last town before the desert, she noticed two Turkish women moving among the group. They were asking whether anyone knew how to sew. The daughter of one lady was getting married and needed a trousseau. When my mother told them she was a seamstress and knew the art of French dressmaking, they demanded proof—the scissors, tape measure and thimble provided it and, thus, saved her life.

Following the war, my mother settled in Constantinople and, while there, found two of her three sisters and her brother. In the meantime, my father, who was living in Minneapolis, wanted to establish a family. He wrote to a friend in Constantinople to see whether she might know a suitable bride. My mother was asked whether she would be interested in going to America. She agreed to correspond with my father, they exchanged photographs, and he proposed. She accepted the proposal with the proviso that her two sisters and brother must accompany her. They arrived at Ellis Island in March 1921, were married the following week, and had a wonderful marriage for 54 years. I was the youngest of their five daughters. Our household was filled with love, books, and music.”

A passion for music

“While I was a young child, my parents realized I had a beautiful voice and they always asked me to sing for guests. When I was a teenager, my oldest sister had a friend who was close with Gladys Swarthout, a Metropolitan Opera diva. That friend helped schedule an audition for me with Miss Swarthout, who was thinking of taking on a protégé and would be in nearby Chicago soon for some performances. The day before the audition though, Miss Swarthout became ill and cancelled her performances and my audition. I was devastated but further reflection suggested that God had other plans for my life.”

Career catalysts

“Starting at about age 4, I loved to collect earthworms, especially after a good rain. I’d take them apart to see what I could find. I think that was the beginning of my career as a pathologist. Then, when I was a teenager—right around the time of the canceled audition—I read The Magnificent Obsession by Lloyd Douglass. It’s the story of a feckless playboy who inadvertently causes the death of a famous neurosurgeon. He tries to make amends by studying medicine. I was inspired by the man’s drive to right his wrongs and to become a neurosurgeon.”

Advice from a trailblazer

“I tell everyone to pursue what they love. If they do, they won’t be looking at the clock all day. My parents gave me two pieces of important advice: 1) study and learn as much as you can as you never know when you will need that knowledge and 2) when someone gives you a job, do it as well as you can and with a smile on your face.

People often ask me if I experienced issues in my career because of my gender. I never felt any serious problems. I was always treated well. Women certainly had a difficult time getting into medical school back then, but when I was accepted I worked hard and loved it.”

Proudest moment

“Although I have many, here’s one. In my 1981 Presidential Address to the American Association of Neuropathologists, I challenged a world authority on his long-held theory about embryonal pediatric brain tumors. That gentleman was not pleased. But by challenging him, other colleagues realized that this was fertile ground for study. In consequence, there have been many advances in our understanding of this group of childhood tumors.”

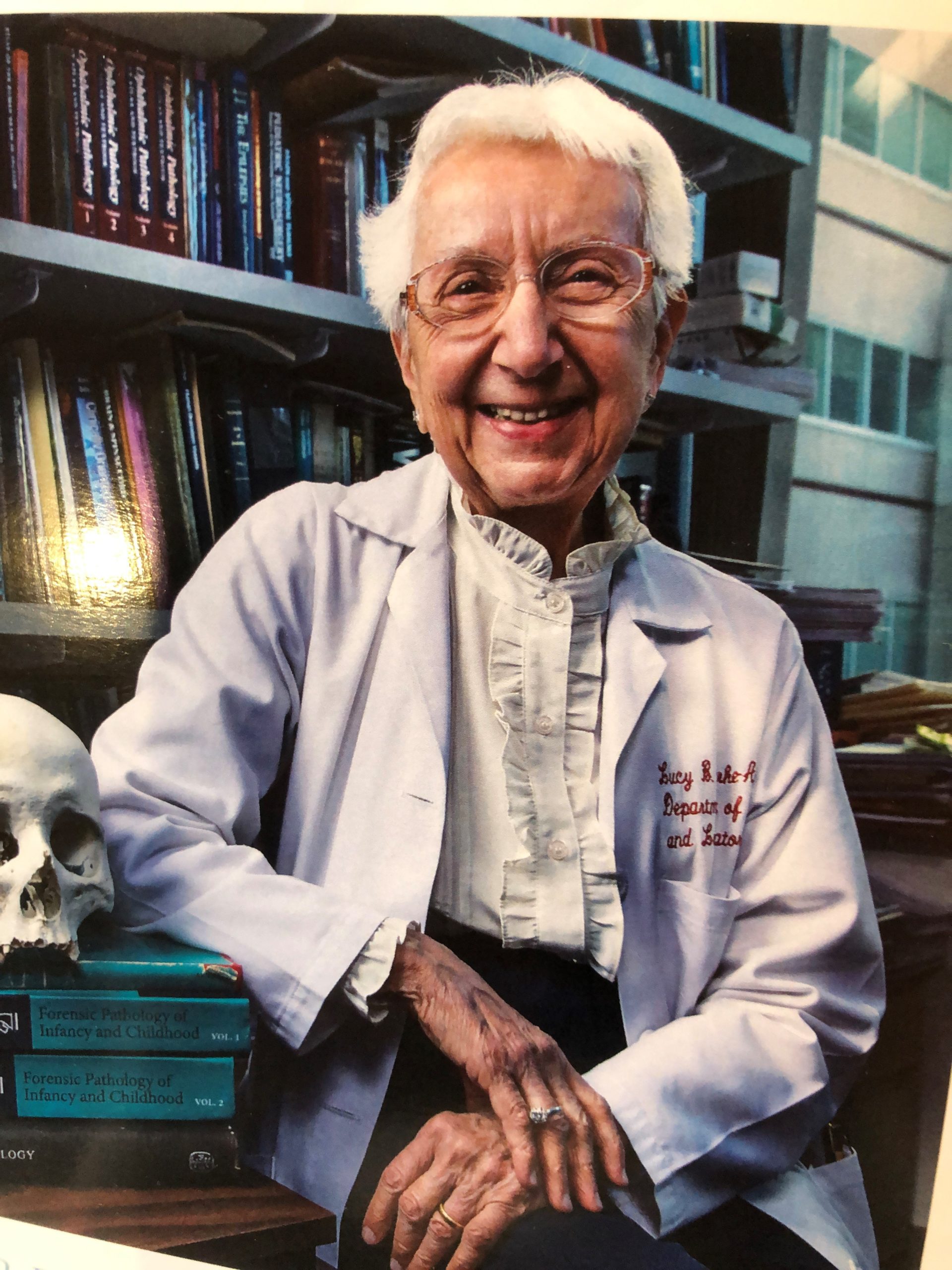

A beautiful brain

“In 1955, Dr. Thomas Harvey, the pathologist at Princeton Hospital, performed an autopsy on Albert Einstein. Five sets of microscopic slides were then made at the pathology laboratory of Dr. William Ehrich at the University of Pennsylvania. Dr. Harvey and I were students of Dr. Ehrich, though he preceded me by some years. Dr. Harvey gave one set of slides to Dr. Ehrich and some years after his death, they were given to me. Dr. Einstein died when he was 76 years old, but his brain was that of a young person. After guarding them for many years, I decided that they belonged in a museum and gifted them to the Mutter Museum of The College of Physicians of Philadelphia where they are on display.”

Reasons to give

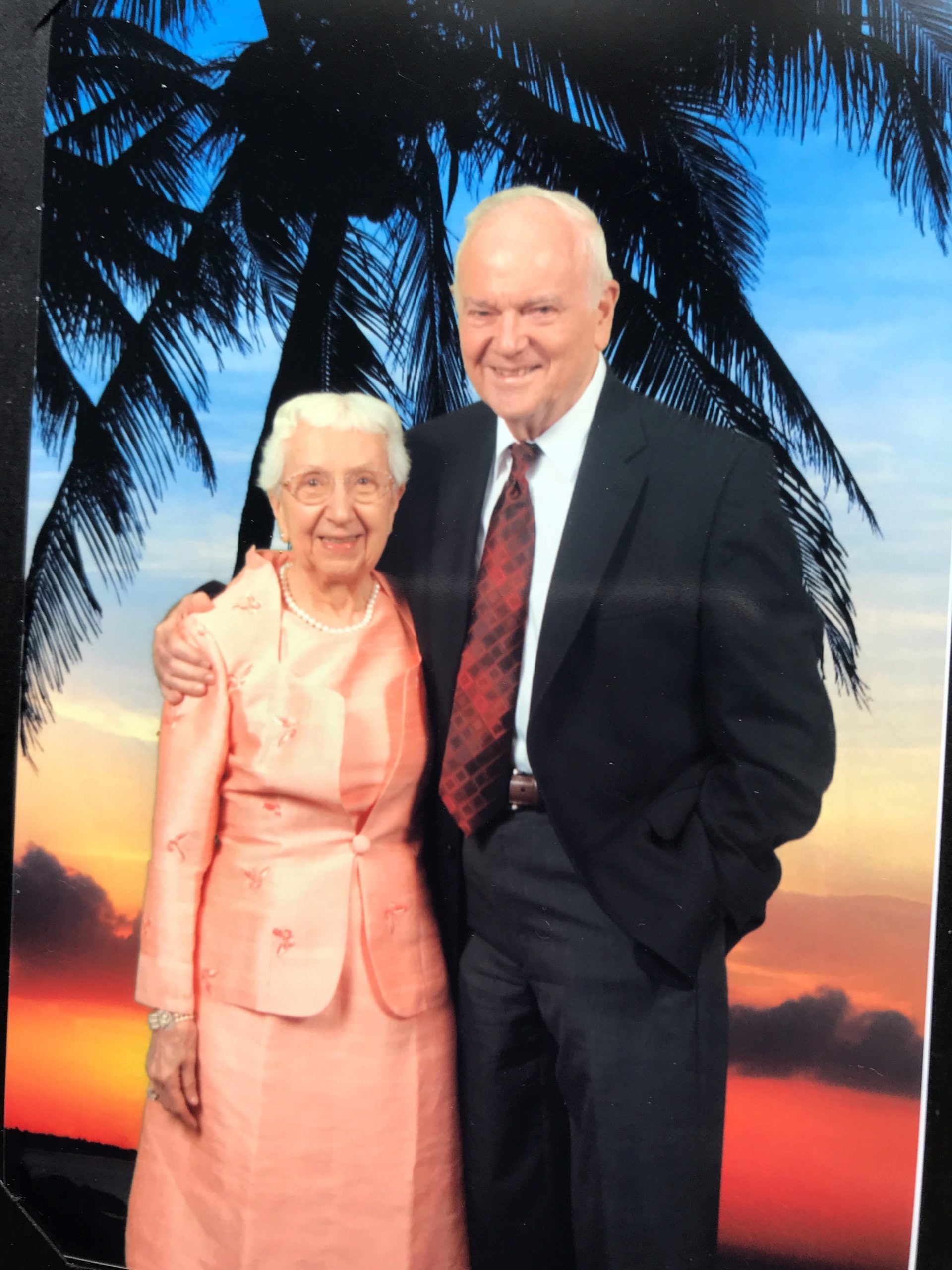

Dr. Rorke-Adams with her husband, C. Harry Knowles

“My parents instilled in me the importance of making my life count for something by sharing whatever talents I possessed with society at large. I tried to do that by focusing on advancing science in the hope of improving the lives of children. My late husband, C. Harry Knowles, was a brilliant scientist and physicist who held more than 400 patents and succeeded exceptionally in the company that he established. He shared a desire to invest in the next generation and chose to do this by establishing the Knowles Teacher Initiative. This initiative supports teachers by advancing their skills in teaching math and science to high school youths.”

A shared commitment

“Harry and I developed a deep friendship with Dr. Alex Levin and his wife, Faith. When we first learned of his pioneering work identifying and treating genetically-induced diseases of the eyes, we decided to support him. At that time Dr. Levin was working at Wills Eye Hospital in Philadelphia. When he became chief of pediatric ophthalmology at the University of Rochester Medical Center’s Flaum Eye Institute, we redirected our support. My husband was a modest man with a profound altruistic outlook who pledged to continue supporting Dr. Levin’s important work. It now gives me great pleasure to carry out his wishes by formalizing a bequest at Flaum that will do just that.”

Life today

“I still live in New Jersey, and I just completed my third autobiography for a medical journal, this time for the Annals of Pathology. I am embarking on a major effort to write the history of my parents and ancestors primarily for their great grandchildren who will never know what a distinguished lineage they have. Otherwise, I enjoy reading biography and history and derive great pleasure in classical music especially Bach, Mozart, the other greats, and, of course, opera. For 35 years, my husband and I reveled in attending Saturday matinee productions at the Metropolitan Opera House and I look forward to attending a performance of Eugene Onega in April as the Levins’ guest.”

Make a difference

Contact Michael Fahy, assistant vice president of University of Rochester Medical Center Advancement, to learn how you can support our medical faculty, research, and programs.

*Alex Levin is also the Adeline Lutz – Steven S.T. Ching, M.D. Distinguished Professor in Ophthalmology at the University of Rochester Medical Center.

Interview by Kristine Kappel Thompson, March 2022