This is the second summer that University students – led by professors Renato Perucchio, Michael Jarvis, and Chris Muir – are studying the engineering, historical, and cultural aspects of the coastal forts of Ghana. They will be sharing their experiences from the field here on this blog.

By Ewan Shannon ’20

My book of choice for my time here in Ghana has been West with the Night, a memoir by Beryl Markham recalling her days in East Africa as a freelance pilot and racehorse trainer in the 1930’s. Although the book doesn’t take place in Ghana, I thought it would be appropriate because of the continent it takes place in.

One recurring theme of her book is the idea of unfamiliar territories. I find myself right now in very unfamiliar territory, both academically and geographically. The group of students I am with are largely mechanical engineering majors, and a good amount of the professors are cut from the same cloth. So, a lot of the questions we set out to answer about digital archaeology here along the coast of Ghana are taken from that angle. It would be very easy for me to give a dismissive “why should I care?” when I measure the dimensions of my third vaulted room of the day, or listen to my professor describe a collapsing wall as a “moment of rotation,” but instead I am enjoying the challenge of genuinely trying to answer that question. What does the engineering behind these historic structures mean to me? I believe that is a question more worth answering, since I am already somewhat familiar with what these structures mean to me historically, anthropologically, and emotionally.

The goal of this entry isn’t to try and definitively answer these questions, but rather to discuss how I got my feet planted. The first step was to acknowledge that I am not here to be comfortable. I am not here to learn things I already know, just like I am not here to eat food I already like and see things I can see back home. If I stick to what I am comfortable with, I cannot grow. My hopeful future as an archaeologist will be better served by a more holistic schooling in which I can answer all sorts of “why’s” and “how’s” and “when’s” about the people and their places.

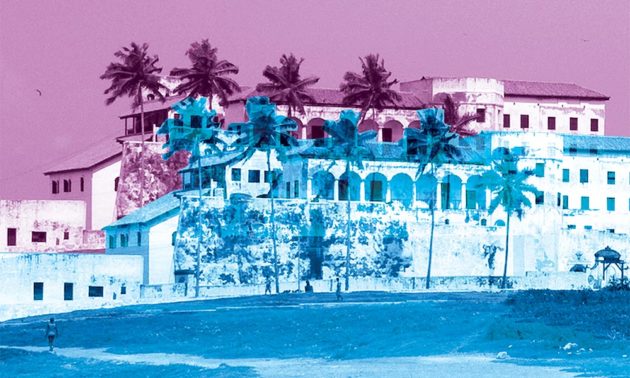

The second step was to find common ground. One of my favorite similarities so far between the “conventional” archaeology I am familiar with and what we are doing at Elmina Castle and Fort Amsterdam is the importance of chronology in understanding what we observe. In both cases, distinct periods of occupation and a terminus post quem (earliest time an event may have occurred) or two help us get a fuller picture of what we observe in the current day.

The difference lies in how the chronology presents itself to us. Ideally, when you’re excavating in the ground, the rule of superposition is king; the features and artifacts are like a neat stack of newspapers in an attic. The oldest ones are at the bottom and the newest ones are at the top. When establishing the chronology for the construction of, say Elmina Castle, it’s like someone took those newspapers, slathered them in glue, and made a nice piñata out of them; a piece from one era is partially covered by another of a different time, and one section can be entirely made from one time period and then abruptly stop and be taken over by another.

This also happens to be one of my favorite challenges, going around Elmina Castle and trying to figure out what is Portuguese or Dutch in construction before one of my professors points it out.

So, in trying to answer the “why should I care?” I have learned not just what different types of bricks look like, but also how the forces in an arch work and play out in the real world, and why engineering is far more relevant to historical study than I initially gave it credit for. I have learned how to make all sorts of models on the computer (photogrammetry is quickly becoming a favorite of mine) and how to use a Total Station. I have learned about the Elmina fishermen and boat builders, and also have received an introduction to the town’s economics, history, social stratification, and even cuisine as a result. I have also learned, thanks to Kakum National Park, that maybe heights aren’t as scary as I thought. And I have only realized just how much I’ve learned in these two weeks as I write this.

In her closing chapter, Markham starts by saying that “past places seem safe ones, vanquished ones, while future places live in a cloud, formidable from a distance. The cloud clears as you enter it.” For me, the cloud has been lifted much more than I thought possible in these past weeks. This is all unfamiliar territory, but that’s exactly why I should care.

Ewan is a rising junior from Staten Island, New York. He is a Renaissance and Global Scholar majoring in ATHS (Archaeology, Technology and Historical Structures) and anthropology. He is particularly interested in conducting ethnographic work in the community surrounding Elmina castle and making photogrammetry models of the forts. Ewan is also an actor in the university’s International Theatre Program, and enjoys gardening, Civil War history, and Buster Keaton films.