Eva Hansen ’18, a biomedical engineering student at the University of Rochester, has traveled to the Dominican Republic two times with an Engineers Without Borders student chapter to help provide an elementary school with access to clean water.

Eva Hansen ’18, a biomedical engineering student at the University of Rochester, has traveled to the Dominican Republic two times with an Engineers Without Borders student chapter to help provide an elementary school with access to clean water.

And because of the unique design of Rochester’s undergraduate curriculum, Hansen has been able to augment her major and EWB experience with a “cluster” of courses in public health.

Those courses have allowed her to see the problem of water access in a much broader light than she might have without them.

“Lack of access to clean potable water is, at its root, a public health disparity,” she says. “Public health can provide an academic lens with which to view the impacts of a lack of clean water, as well as provide a framework to implement effective community-based change.”

Hansen’s public health courses are a reflection of the remarkable degree of autonomy Rochester allows its undergraduates as they choose the subjects they want to pursue—and in a meaningful way.

The Rochester Curriculum, approved in 1995, opened the curriculum by removing specific sets of general education requirements. However, this by no means a “free elective model,” such as curricula adopted by a number of institutions following the turbulent ’60s, which make no prescriptions at all.

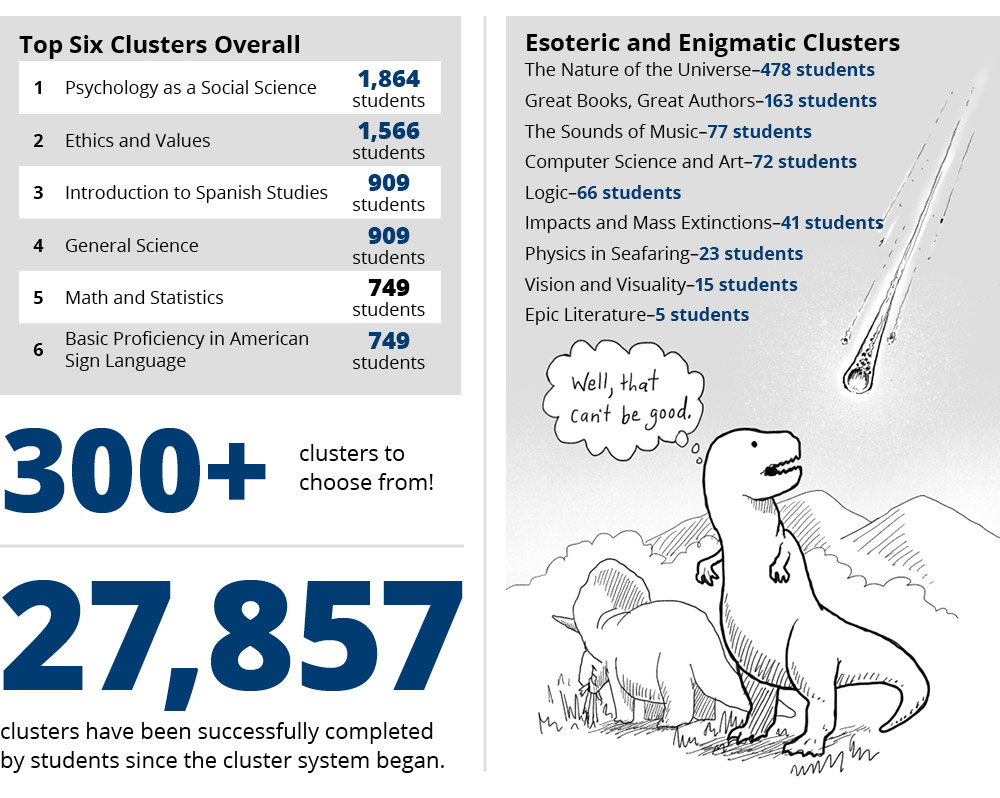

All students take a required primary writing course – usually Reasoning and Writing in the College (WRT 105 or 105E) – and fulfill a program of study in each of three areas of learning – humanities, social sciences, and natural sciences/engineering. Students select a major in one of these areas, which they can combine with an additional major, a minor, or a cluster in the two remaining areas (engineering students, whose major programs are guided by the Accreditation Board for Engineering and Technology, or ABET, are allowed to choose one). In meeting this requirement, students can choose from among some 300 so-called clusters—sets of three related courses—designed to provide an in-depth exposure to a discipline. The clusters are also spread across these three areas of learning: arts and humanities; social sciences; and math, natural sciences, and engineering.

Within this framework, the Rochester Curriculum is premised, first and foremost, on the idea that “students should have the autonomy to decide for themselves what subjects they will pursue,” a University committee noted in 2016.

The notion clearly resonates with prospective students, and has helped make the curriculum a defining aspect of the Rochester college experience.

“It allows students to see themselves in the driver’s seat,” says Scott Clyde, executive director of College Enrollment. According to Clyde, “more than 90 percent of incoming students surveyed last year indicated that Rochester’s unique curriculum had a positive to strongly positive effect on their decision to enroll.”

Jeffrey Runner, dean of the College, finds that the curriculum attracts self-starters, while helping to teach less confident students how to find their own path.

“The challenge is that students have to learn how to navigate,” he says. “You don’t just get handed a schedule. You have to take ownership of your program, your career, and your life.”

People like Laura Gavigan, associate director of the College Center for Advising Services, are there to help.

Gavigan notes that most students take 32 courses before graduation, including 12 (typically) for a major, six for two clusters, and the required primary writing course.

“That leaves 13 other classes you can take,” she says. “Perhaps yoga, anthropology, or another class not necessarily applying to a major, minor, or cluster. It’s really inspiring when students pursue their curiosities and move beyond their comfort zones.”

Muster the cluster

While the basic design of the Rochester Curriculum has remained the same since its creation, one of its key components—the clusters—are constantly being revised. This keeps the curriculum anything but static.

During the 2017–18 academic year, for example, new clusters were approved for the University’s Writing, Speaking and Argument Program, Modern Languages and Cultures, Art and Art History, Optics, Religion and Classics, and by the Hajim School of Engineering and Applied Sciences. Several of the Hajim School’s clusters were specifically proposed to provide an engineering perspective on questions of social change and technological advance for non-engineering students.

Alan Czaplicki, associate dean of the College, oversees the management of the cluster system and works with faculty on the College Curriculum Committee in approving new and revised clusters. He notes that this year the committee has taken a “deep dive” into examining the variety of ways that clusters can be used by students and departments to generate interest in a variety of different disciplines. This leads to interesting questions on the different purposes and structure of clusters across the curriculum.

“Clusters are the centerpiece of the Rochester Curriculum and as such generate always interesting discussions on how students delve into and use clusters to further their knowledge,” Czaplicki says.

Creating and exploring: Take Five, dual degrees, and self-designed majors

Clusters aren’t the only means by which Rochester students explore multiple disciplines in a meaningful way. They can also pursue the Take Five Scholars Program, which, unique to Rochester, offers selected students a fifth, tuition-free year to pursue an intellectual interest or theme outside the major; dual degree programs; or self-designed majors.

Meanwhile, both students and faculty note that the curriculum has had some unforeseen benefits.

For example, some students find that a cluster sparks their interest so much they decide to complete a minor or a second major in the subject. That’s been the case in the Department of Computer Science, where a number of female students in the department have developed an interest in the field through a first encounter via clusters.

“As an outcome of the cluster system, many students begin to take a cluster in Computer Science to fulfill their breadth requirement and enjoy it so much, it grows into a minor or even a major,” the department concluded in a report on its efforts to broaden the participation of female students. “This is one of the ways we draw women into Computer Science: they begin a cluster and then add a major as their studies and interests continue.”

The percentage of women in the department’s 2017 graduating class was nearly double the national average.

And for students like Eva Hansen, the latitude afforded her by the Rochester Curriculum helped her achieve some important goals. Because she can link her public health cluster to her major in biomedical engineering and to her experiences with Engineers Without Borders, it is helping her qualify as one of the University’s first National Academy of Engineering Grand Challenges Scholars.

“At several of the others schools I was considering, the approach to distribution courses was very prescribed,” she says.

“I appreciated that at Rochester I would be able to choose distribution courses that I felt genuinely interested in and desired to explore, given the limited courses I could take outside of my major.”