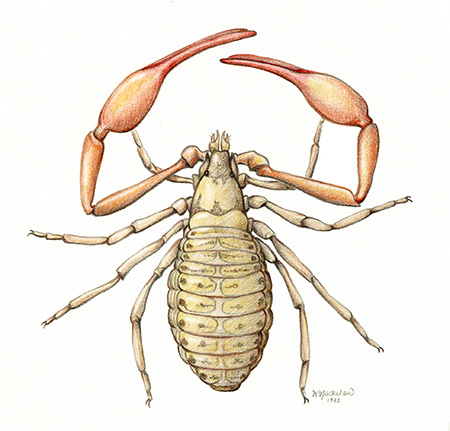

At the height of his career, only a half dozen other researchers in North America shared William Muchmore’s interest in pseudoscorpions – small arachnids with pear-shaped bodies and pincers similar to scorpions, but without the tails. After all, they were not known to have any economic or medical importance. They were also small and “tedious to study,” said the former University of Rochester biology professor, who died in May at the age of 96.

But that did not deter him from becoming a leading authority on the “fake scorpions,” discovering and naming more than 290 new species during a research career than spanned nearly four decades.

“These interesting and very tiny creatures are related to true scorpions but live quite secretive lives,” says Jerome Kaye, a professor emeritus who served in the department with Muchmore. “Only a dedicated expert is likely to find and recognize one. Bill became known internationally as one such an expert.”

Muchmore’s research continues to be highly regarded and cited, according to Mark Harvey, senior curator of arachnology at Western Australian Museum and a leading expert in the field. “His insights into pseudoscorpion taxonomy have led to many new discoveries, such as new genera and species,” Harvey says. “While many people are amazed that we are still discovering new species, Professor Muchmore was able to describe more than 290 new pseudoscorpion species during his career, providing valuable information on how to identify each species.”

In honor of his outstanding research, Muchmore’s peers named seven species and a new genus after him.

An expert in the diversification of living forms

Muchmore said that he enjoyed the opportunity to “uncover knowledge about things in the world that are not known.”

He was a specialist in systematic zoology—the study of the diversification of living forms, both past and present, to understand the evolutionary history of life on Earth. He studied the relationships of pseudoscorpion species to each other and to their geographic distributions, and what this might reveal about their evolutionary adaptations.

In 1970, his collection of 1,900 samples of North American pseudoscorpions, some saved in small vials and some mounted on microscope slides, was considered one of the largest in the world. He published nearly 150 papers and book chapters on pseudoscorpions, and was supported in his research with several National Science Foundation grants.

He also studied embryonic development. “Bill was an experimental embryologist who asked how the fates of different tissues in the embryo were determined by their locations in the developing embryo,” Kaye says. “He used salamander embryos in this work and did exquisitely delicate surgical techniques to transplant parts of embryos from one site to another.” Kaye recalls collecting salamander eggs with Muchmore one spring, “wading in a pond at night with the sounds of spring around us, frogs and toads and spring peepers all calling for mates. Quite a treat for a biologist.”

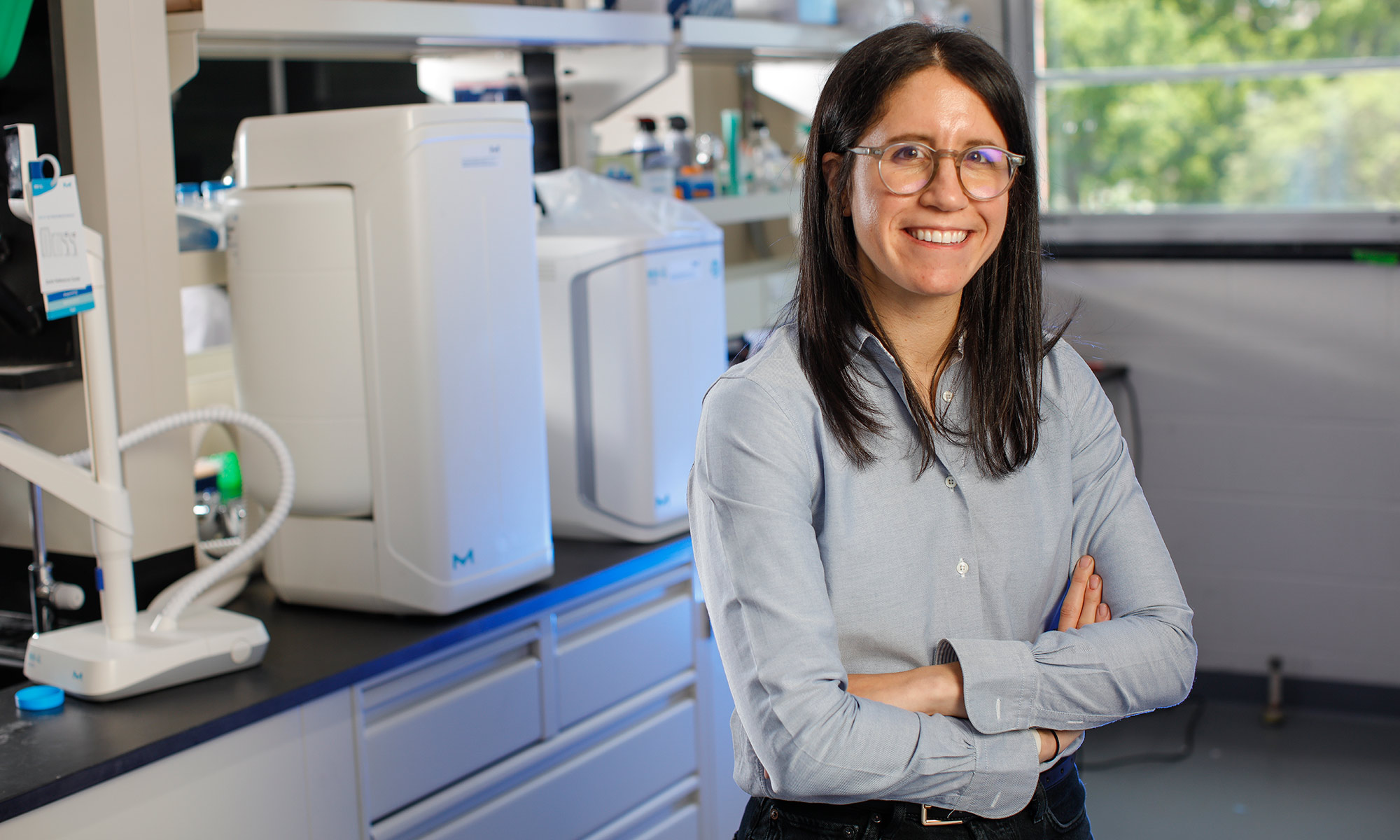

A valued colleague and teacher

Born in 1920 in Cincinnati, Ohio, Muchmore received an AB degree in zoology from Oberlin College in 1942. He served as a US Army medical laboratory technician in the Pacific during World War II, then attended Washington University in St. Louis where he received his PhD in 1950, the same year he joined the Rochester faculty.

Kaye, who joined the department in 1959, says his first impression “was that Bill would be both a good colleague in academic affairs and someone with a positive, likable personality who would be an excellent teacher. My subsequent experience bore out and amplified this initial impression. In fact, Bill was simply an all-round valuable member of our department.”

Professor emeritus Stan Hattman, another colleague, says he was “always impressed with [Muchmore’s] insights on education and departmental political issues, which he always presented in a clear and calm voice. I’m sure that demeanor endeared him to his students as well.”

In 1966, Muchmore was one of 14 inaugural recipients of a newly established University award to recognize faculty members for outstanding teaching, as voted by juniors and seniors.

Brenna Rybak, administrator of the biology department, says she has met several of Muchmore’s former students at Meliora Weekend Open Houses over the years, and received emails “out of the blue” from others – all interested in contacting the professor. “They have all spoken very highly and passionately about what a great teacher he was and how he affected their lives.”

Count Wendy Beth Jackelow ’83 among them. Jackelow took Muchmore’s vertebrate zoology class her junior year. But she enjoyed art classes as much as biology, and would illustrate her notebooks with detailed drawings of specimens. “He said to me, ‘Do you know there is a career in medical and scientific illustration?’,” she says. “I had no idea such a thing existed; but I knew, the minute he said it, that this was what I was meant to do.”

After she enrolled in the medical illustration program at nearby Rochester Institute of Technology, Jackelow contacted Muchmore to brainstorm ideas for her master’s thesis. He suggested that she illustrate a checklist he was preparing on the terrestrial invertebrates of the Virgin Islands. “I knew I had hit the jackpot,” she says. “It was exactly what I wanted to do and [he was] exactly the kind of person I wanted to work with.”

After completing her master’s degree, Jackelow worked as a medical and scientific illustrator for hospitals and a publishing company, before going into business on her own.

She says she thinks about Muchmore every day. After all, “he set the course of my life.”