The Rochester Review, University of Rochester, Rochester, New York, USA

By Kathy Quinn Thomas

Sunny day, sweeping the clouds away. . . ." As familiar to most college students as Twinkies and chocolate milk, the recorded sounds of the "Sesame Street" theme song bounce along the lower level of the University's Interfaith Chapel.

The mumbled conversations of 80 still-sleepy undergraduates can barely be heard over the playful music, their voices a little slurry through bites of bagel and cream cheese.

The room's panoramic window wall offers a view of a near-perfect morning: Three days of rain have washed the mid-August air clean and now it is warmed by a vivid sun. Late-summer weeds along the Genesee River glow bright green, ready to drop their pollen.

At a time when most students are still working summer jobs and savoring that last precious bite of non-academia, these jeans-clad, tee-shirted, backwards-capped undergraduates are taking two precious summer weeks to polish the skills they'll need as this year's crop of River Campus resident advisors.

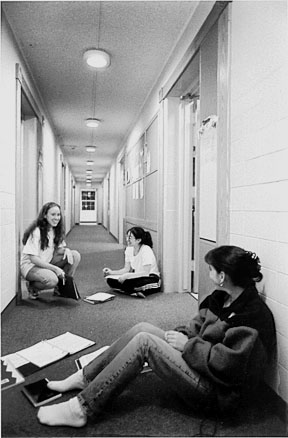

As most alumni remember, RAs play a pivotal role in a smoothly running residential campus like Rochester's--a compact neighborhood of some 2,700 undergraduate residents. Assigned one to a floor in most campus residences, RAs function as sort of professional big brother/big sister to their charges, combining the roles of, among others, cheerleader, counselor, town crier, social director, conflict manager, and first-line emergency response team.

Since most undergraduates live in University housing (sophomores as well as freshmen are now required to do so), RAs are among Rochester students' earliest and most important personal contacts.

Rigorously selected and as rigorously trained, undergraduate advisors counsel their residents on how to adjust to living and studying on campus, including advice on how to get along with roommates and next-door neighbors; pass along tips on where to go for further assistance on almost anything; and serve as the first stop for help in emergencies. (An emergency can be anything from the loan of a curling iron or replacement of a lost door key to dealing with a disruptive resident or helping a hallmate cope with the sudden loss of a loved one.)

The students trade these time-consuming responsibilities for the cost of their rooms. "If you ask an RA why he or she is doing it, the answer is usually, 'for the money,'" says Logan Hazen, director of residential life. "But there's a lot more to it than that. These kids could make more money per hour washing dishes in the dining hall or putting books away in the library. Instead, they choose advising. It is definitely not something they do just for the money."

On this August day in the chapel's lower level, Hazen is the only person in the room wearing a tie. That power symbol, and the sound of his voice coming from the podium, gathers the bagel-chewing bunch to their chairs.

Hazen makes several announcements, then introduces the day's speaker.

Educational consultant Maura Cullen arrives a little late, after being stranded at the airport in the storm that brought the day's Sesame Street weather. Her subject is building community in a diverse environment, one of the primary charges to residential advisors. (Other topics for the two-week training session include team-building, counseling skills, Internet training, health services, academic support, community service, and social-event programming, along with knottier topics like how to deal with eating disorders and substance abuse.)

The essence of community building lies in forging coalitions, Cullen says. When individualism and survival of the fittest rule in a group, she warns, there can be no sense of community.

To make the point, Cullen sets the students a project: Find a way for one of them to take a bright blue-and-yellow football and, within a set number of minutes, have everyone else touch it--no small feat with 80-odd players involved. The result? Students, scattered across the room, haphazardly throw the ball from one to the other.

Cullen cuts the time limit in half, and asks them to do it again--this time in a different fashion, while making sure that the same people touch the ball in the same order they did before. After much ado, the players decide to stand in a circle approximating the original order of contact while the first student circulates with the ball, touching it to each of the players.

Cutting the time yet again--to a bare two minutes--Cullen has her charges try once more. Several brave souls take the lead in coming up with a workable solution: The students form two parallel lines, hands out ready to make the touch as the ball-carrier sprints between the rows.

The touch-football workout is the last in the morning's series of exercises designed to illustrate aspects of team-building. "Which of those projects made you feel the greatest sense of community?" Cullen asks the group after they settle back in their chairs. The answers vary, with some saying they enjoyed the informal moments and some preferring the formal.

"Community means different things to different people," Cullen summarizes. "As an RA, you are supposed to build community on your floor, but that doesn't mean that you should expect everyone to do everything the same way. We want to create a climate where everyone feels welcome, but where they can come in and out as they wish."

This roomful of RAs, charged with community building, exemplifies the diversity of the student body as a whole, Hazen says later. RAs come from all backgrounds, and from all parts of the globe, with interests in everything from semiconductor chips to the poetry of Yeats. They have, however, one common attribute, he declares. "They are all exceptional."

In order to be accepted as an RA, students must have a minimum 2.5 cumulative grade-point average. Slip under that and the RA faces, first probation, then eventual loss of the RA position.

But Hazen doesn't worry much about bumping RAs, he says. The average GPA for last year's crop was a whopping 3.57, with 18 percent of them attaining a perfect 4.0.

They're just amazing," he says. "In about 99 percent of the cases, even with the added responsibilities, these students either maintain their GPA at the same level it was before, or it actually goes up. And this is true no matter what their outside activities."

And the outside activities can be formidable. Hadijatou Jarra '99, a biology major headed for medical school, is president of the Charles Drew Premed Society, a member of several other clubs, and a volunteer with a local mental health services agency. She is back for her second year as an RA.

Her post last year in Burton Hall was, she admits, challenging. "I come from Baptist North Carolina, where everyone seems just like me," she says. "I've grown a lot here, meeting all kinds of people, learning how to tolerate differences, working things out."

First-year resident advisor Nihar Mehta '00 is another who is juggling serious academic goals (a major in economics and minors in both psychology and English) with a hefty dose of extracurricular activities (student government President's Cabinet, Campus Times reporter, crew).

"It's a heavy load, sure, but I really want to do it all," this Bombay native says. "When I first came here, it was a serious culture shock for me until I got used to

things. But my RA last year made my life livable--really--and now I would like to do the same thing for other people."

Jennifer Mauskapf '00, a Pennsylvania native and sociology/Spanish major, says it was the opportunity to work with other students that helped her decide to become an RA. "I've always wanted to be a counselor," she says. "And the RA class last spring helped us explore that, taught us how to be paraprofessional counselors." (In addition to the two-week summer program, RAs also take a semester-long, credit-bearing course in the spring.)

Mauskapf has plenty of plans for the residents on her floor this year. "We'll

have a mixer, go to see Miss Saigon and Annie, do some kind of community service. I have more ideas for events than I'll be able to use."

But, as these students well know, an RA's year is filled with more than social events. As Hazen points out, "They learn pretty quickly that it can definitely have its drawbacks.

"You live in a fish bowl," he enumerates. "You lose your identity, getting introduced to everybody solely as 'my RA.' You can't leave early for vacations. You get swallowed up in paperwork. You are the main point person for emergencies, often enough in the middle of the night."

Jarra concurs. She had to deal with what she euphemistically refers to as "a lot of situations" last year, and she had to learn just how much she could do about them. She cites the case of one of her residents, a young woman with a serious eating disorder. Her friends, concerned, went to Jarra for help. After much counseling and referrals for professional assistance--culminating in a scary trip to the emergency room--Jarra finally realized that she could go only so far in working with the student. "I just couldn't fix the problem. There was nothing more I could do. Continuing to live with the disorder was her choice. I had to learn to just back off."

Another second-year RA, Ross Liebman '99 (math major, Campus Times photographer, soccer player), like Jarra describes his last year's experience as a challenge, but also as one that was ultimately satisfying. "I had to deal with a disruptive student who smoked (on a non-smoking floor), drank, and generally had a negative impact on the freshmen around him," the Long Island native says. After talking with his supervisor about the problem, Liebman confronted the rowdy resident about his bad behavior, and eventually, Liebman is relieved to report, it abated.

The "situations" haven't kept either Liebman or Jarra from coming back for another RA year. The down moments are more than balanced by the up, Jarra says. "One of my residents last year came up to me and told me that she had serious respect for me--that I was the one who did the most for her in her freshman year.

"Even with all the paperwork and the emergencies, it just made me proud to know that I could really do that for someone."

Kathy Quinn Thomas reported on "Depression and the Golden Years" in the last issue of Rochester Review.

Copyright 1997, University of Rochester

Maintained by University Public Relations