The Rochester Review, University of Rochester, Rochester, New York, USA

Tylenda on the job as a student managerory Tylenda '99 looks just a bit like the elected politician he hopes one day to be as he approaches the boisterous group of young people seated at a table in "the Pit" at Wilson Commons. Dressed in a neatly pressed striped shirt and tie, the political science major from North Rose, New York, stands out like Mr. Rogers in an episode of South Park.

The noisy group at the table quiets, as if to listen.

But Tylenda is not there to get their votes or to lecture them on civic duty. He's there to tell them to get back to work.

Break's over.

Tylenda, a student manager, is the boss. The young people are a team of off-campus temps hired to fill evening shifts for dining services, making sandwiches at Blimpie's, tossing burgers at the Grill Works, washing dishes, and cleaning up the kitchens.

While happy to have the help, Tylenda longs for a day when all his workers might be students.

"Students are the best employees for University Dining Services," he says after the table is cleared. "They have the most interest in their peers, and they have a stake in the quality of the food and service they're providing."

But Tylenda, who has worked for four years in dining services, routinely has at least three student positions open on any evening shift.

As for his wish that more students would work in dining services, or at least that the ones who do work there would put in more hours, he's wishing in vain, say University employment officials and experts across the country. The nature of student employment at colleges and universities is changing: Students are more active in seeking out the jobs that they think will look good to future employers and more careful about maintaining a balance between academics, work, and social life.

Campus employment has been a mainstay of college life for nearly as long as there have been colleges. Schools rely on students to fill part-time jobs as cooks, dishwashers, book-shelvers, couriers, data entry clerks, receptionists, and clerical assistants--any task that requires a willing worker and a commitment of some 10 to 20 hours a week.

Traditionally, the relationship is two-way: Universities need a steady supply of employees, and students need supplemental income for tuition, books, weekend money, or other expenses.

In recent years, undergraduates at Rochester and on campuses elsewhere have begun migrating away from the time-honored occupations for student employees--the "just for the

money" jobs, as some career counselors call them--to more technological, sophisticated jobs. Jobs working with computers are particularly hot right now.

While that generally is good for post-graduation career prospects, the trend, along with other factors, is putting a crimp in the labor pool for some of the more traditional campus jobs, employers say. Many jobs go begging or are filled by non-student temporary employees, which, in turn, affects the "student-oriented" service that they try to provide.

Take dining services, home of the quintessential "just for the money" job: On any given day, as many as 30 temps are working at Danforth, the Meliora (née Faculty Club), Douglass Food Court, the Pit, the Coffeehouse in Wilson Commons, and Eastman Dining Center, as well as the various food carts operated by dining services.

In the past, those jobs would have been filled by students.

On a busy day at the close of the fall semester, Diane Dimitroff, senior administrator of the department that oversees dining services for the River and Eastman campuses, talks about how that trend has affected her department. In 1995, for instance, the unit hired 500 student employees, each working an average of 10 hours a week, for a labor pool of about 5,000 hours a week.

The more modest 1998-99 goal was to hire 300 employees for 3,000 hours a week.

"And we're probably still short 800 student hours every week," Dimitroff says. "If students are working, they're not working for us. It's been scaling down for the past three or four years."

One factor that probably affects employment on campus is the size of the labor pool.

To enhance the undergraduate experience, the College has been enrolling smaller entering classes--moving from an undergraduate student population of some 4,500 in the 1980s and early '90s to a projected 3,600 this fall.

Beyond that, however, is a changing attitude toward work.

Philip Gardner, director of research for the Collegiate Employment Institute at Michigan State University, says most studies show that people under the age of 32 are less likely than their elders to emphasize work as the most important aspect of their lives. Researchers aren't sure why, but many speculate that the current group of young people grew up watching their parents' 40-hour-plus workweek erode their family life.

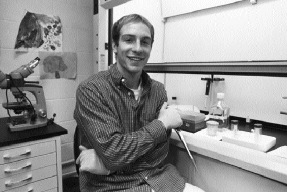

Ames on the job as a lab assistant"Students today will work hard, but they want to work fewer hours a week," Gardner says. "It's not that they don't have a work ethic, but, on the whole, they are looking for balance in their lives."

Rochester's Burton Nadler, assistant dean and director of the Career Center in the College, says the opportunity for students to move out of the "just for the money" jobs to fairly sophisticated, technology-based jobs is one of the features that make the University appealing to undergraduates and their parents. It also allows students to be more particular about the work that they do.

Nadler says it's a natural progression for students to move on to more challenging jobs as they become familiar with other opportunities available on campus. (Nadler's department has made that super-easy, through an online jobs listing available through the Career Center website: www.rochester.edu/careercenter/seo.html.)

"Do they all move into more specialized work? No. Some choose to stay in the 'just for money' jobs. Maybe they like the hours or they like to be with their friends or to be done with their work when they're off the clock," he says. "Do we encourage students to actively look for opportunities in their own fields? Yes. It's a natural trend, although it's not ideal for everyone."

"Employers today are looking for graduates who have, if possible, risen above the less-skilled jobs," Nadler says. "They're looking for people who have done research. They want the people who have shown the ambition, the drive, the ability to work with our high-caliber faculty scholars."

ome high-tech experience was exactly what Gretchen Ames, a senior chemical engineering major from Hudson, New Hampshire, was looking for in 1997. She had arrived as a freshman who didn't intend to work while at school, but by her sophomore year she decided she would need some experience to better stand out for prospective employers when she graduated. She also decided she could use some extra money.

She applied for a job as a laboratory assistant in the Center for Optics Manufacturing and--having as yet taken only one course in her major--showed up for work at the facility, part of the University's Center for Optoelectronics and Imaging.

"It was pretty overwhelming to start with, but I settled in quickly," she says. Now, she helps design and conduct experiments to develop better methods for polishing the glass and other materials used in making commercial and scientific equipment.

As a bank of experimental polishers--canisters set on their sides in a constant roll, much like old-fashioned rock polishers--rumbles in the background, Ames uses her computer to track the viscosity of different compounds for a "magnetorheological finishing slurry." The goal is to design compounds that polish well but don't deform too quickly--or too much --while accomplishing the task.

Surrounded by inch-thick glass disks attached to metal axles, Ames waits for an ultrasonic tank to finish "counting" particles of different compounds by using a laser to analyze the material. A printout shows a sharp, curving graph, skewed to the left.

"This should be more of a bell curve," she pronounces, setting the printout on the lab bench with other, similarly sinuous graphs.

"The work I do here is going to help me in the future," notes Ames, who is deciding whether she wants to work as an engineer immediately after graduation or go on for an advanced degree. "Either way I go, I will have to do a lot of this sort of thing on my own."

lan Solomon '02, a freshman biomedical engineering student, knows computers will be part of his own future, no matter what career he eventually ends up choosing. That's why at the University Job Fair during freshman orientation he applied to work at the Computing Library and Resources Center. (Familiarly known as CLARC, it's where students can drop in 24 hours a day to use its banks of Macs and PCs and their eye-popping array of software.)

Solomon had worked part time at an Internet service provider in high school and knew he liked the work and knew he enjoyed helping people understand their computers better. At the beehive of activity that is CLARC, he gets plenty of opportunities to do the latter.

As he talks about his job, a student approaches and tells him she is having trouble getting the computer to print her document dark enough. Solomon directs her to switch from the printer named Athos to the one named Porthos (next to Aramis, of course).

"I can do that myself?" she asks.

"Yup," Solomon says and gives her a brief overview of the process. He watches as she returns to the rows of computers.

When she approaches again, Solomon jumps off his chair with an "All right," and hops over to her computer. After a second printing still proves unsatisfactory, Solomon returns to the three printers and pulls the toner cartridge out of Porthos.

"I could maybe make more money if I worked at dining services, but the atmosphere here is much better and much easier," he says, twisting

the cartridge back and forth in his hands. "I'd much rather work here shaking printer cartridges and helping people than spend my time swiping cards at Danforth."

CLARC is one area that is not having trouble finding undergraduate employees, affirms Jason Wagner, supervisor of student staff at CLARC. He processes roughly 150 applications for the 30 openings each year.

"This is the place to be right now, apparently," says Wagner, a '98 graduate who not too long ago was himself a freshman applicant at CLARC. "We have more trouble turning people away than we do getting people to fill the jobs."

But, he says, echoing Michigan State's Philip Gardner, his students want to work fewer hours than did students of the past few years.

"They are more interested in the technical experience than they are in the paycheck," he says. "The paycheck is a nice side benefit."

Providing experience and helping students to benefit from it are important aspects of the relationship between student employees and their faculty employers, says David Wu, associate professor of chemical engineering.

Wu typically employs four or five undergraduates each semester in his River Campus lab, where they help conduct research, carry out lab routines, and keep the office organized.

Wu enjoys the enthusiasm and curiosity that students bring to their work, but he says guiding students to fulfill their potential is what sets the relationship apart from most work settings.

"While I am their employer, I continue to be an educator for them," he says.

teve Stromski '00, a biomedical engineering major, was looking for experience related to his studies when he gave up a "just for the money" job in 1997 to take a post as a lab assistant in the cytology unit of the pathology department. He started with simple tasks, like washing glassware and sterilizing equipment, but soon moved on to helping the lab do sophisticated analyses of DNA.

"I really wasn't going anywhere in my other job," Stromski says. "This is experience that I can apply to the future."

anak Gada '99 also was looking to the future when he moved to CLARC in 1995 after a stint working at the Pit in Wilson Commons. He was hired as a desk consultant, answering questions about computers and helping insomniac users during the midnight to 8 a.m. night-owl shift.

Three years later, Gada is one of 10 lead consultants at CLARC, overseeing training for the 125 student employees of the bustling hub of campus computing.

"I have a marketable good now after working here for three years: a psychology degree and computer skills," Gada says, taking time out between giving directions to some of the staff. "I wouldn't be nearly as well off with a psychology degree and three years of tossing burgers."

And he has a job. Moving seamlessly from undergraduate to professional, Gada joined CLARC's full-time staff this spring.

Scott Hauser, the new associate editor of Rochester Review, says he worked his way through the University of Iowa newspapering, doing construction work, and "de-tassling corn."

A small sampling of the College's 2,500-plus student-employees On the Job

Douglas Clouden '99

Major: Health and society

Hometown: Brooklyn

Campus job: Visitor booth attendantThe first person many visitors to the River Campus are likely to meet is Douglas Clouden. He works up to 25 hours a week in the visitor information booth on Wilson Boulevard, where he dispenses directions, parking passes, and a big friendly smile.

"One of the perks of the job is getting to meet people," he says. "When you open the door of your booth, you have to have a big smile on your face because you never know who is going to be out there--a prospective student, a parent, or whoever."

He hopes, too, that the interaction with a variety of people with differing needs is helping him polish his customer service skills, something he will need for his goal of eventually working for an international health agency such as the World Health Organization.

"It always helps to work on your people skills because you're always going have to deal with frustrating situations and figure out how to make them go better."

Elizabeth Laprade '00

Major: Cell and developmental biology

Hometown: Seekonk, Massachusetts

Campus job: Electronic-billboard programmerEvery few seconds the monitors in Hutchison Hall, Wilson Commons, CLARC, and the River Campus dining areas flash a new announcement. Perhaps it's a campus event. Or maybe the new CD from the Yellowjackets. Silently, the closed circuit system of UR Vision keeps students, staff, and faculty informed.

The woman behind the UR Vision screen is Elizabeth Laprade, who keeps the system updated from a computer terminal in Wilson Commons.

She took over the job from a friend in October and also works a few hours each week in the Common Market store.

For UR Vision, Laprade makes sure submissions for the free announcements get on the system in a timely way. She does some minor editing, but many ads are simply scanned in and uploaded to the network.

"It gives me a few hours where I can do something for money without interfering with my school work," she says.

Marcus Jenkyn '00

Major: Economics

Hometown: Lyme, New Hampshire

Campus job: LocksmithMarcus Jenkyn once locked himself out of his dorm room, a slightly embarrassing incident that he admits is ironic for someone in his line of work. Jenkyn has worked at this job since 1996, helping to ensure that all the locks in the College residence-hall system work properly.

He's on the job 10 to 20 hours a week, making keys and replacing locks in dormitory rooms.

"It was a little hard to pick up on at first, but once I got the hang of it, it was pretty easy," he says, standing in a basement room filled with keys, lock cylinders, metal punches, and other tools of the trade.

Jenkyn plans to work in hospital administration in the future and to attend business school in a few years. As for being a professional locksmith, that's not exactly a key to his goals.

"It's a part-time job," he says with a smile. "It's an income." (And maybe a plus the next time he locks himself out.)

Molly Holmes '00

Major: Ecology and evolutionary biology

Hometown: Potsdam, New York

Campus job: Student manager, Wilson CommonsWhen the full-time staff of the student activities office goes home, Molly Holmes is in charge of the University-managed parts of Wilson Commons.

"It's kind of exciting when I pull the keys out of my pocket to know I have the keys to the whole student union," she says.

Working 10 to 15 hours a week, Holmes is responsible for the work of eight student managers, who in turn oversee 45 other student workers throughout the Commons. The students staff the recreation room, the information desk, and the Common Market store. They also make sure that meeting room reservations go smoothly.

"I wouldn't take another job even if I were offered a lot more money," she says. "I like working in a place that is so central to campus."

"And I feel like I make a difference here," she adds. "Working in the student activities office, I get a lot of exposure to what's going on on campus. It's not like I'm just a manager. I get involved as a student, too."

Amie Carr '00

Major: Double major in political science and economics

Hometown: Fairport, New York

Campus job: Student building manager, River Campus sports complexAmie Carr's job as a building manager in the sports complex may not relate directly to her future goal of teaching, but the job combines other important aspects of her college life.

A member of the varsity volleyball and softball teams, Carr has first-hand knowledge about what's needed in a top-notch sports and recreation facility.

Carr's brother, Chris '98, told her about job opportunities in sports and rec when she was a freshman. She started behind the information desk, checking IDs, answering phones, and handing out sports equipment and keys. Now, she works about nine hours a week as a building manager, helping oversee the 22-student staff in the department.

Carr relied on her experience both as an employee and as an athlete when she served as the volleyball representative to the planning committee for the upcoming $15 million renovation of the sports complex (see Alumni Review, Recreation center wins support from alumni).

"It really helped that I work here," she says, "because I could give input on the way things work, the problems we experience, and the equipment we need."

Matt Heckman '00

Major: Biomedical engineering

Hometown: Woodhull, New York

Campus job: Laboratory assistantMatt Heckman '00 finds new things to like about his job every time he steps into the laboratory. A junior, Heckman helps analyze sequences of DNA in the research lab of David Wu, associate professor of chemical engineering.

"Amazingly enough, we find genes all the time that no one's ever found before," Heckman says. "You get lost in it, but when you take a step back from it, you go, 'Wow, this is amazing stuff.' "

After working for two years at dining services, Heckman started his lab job last October. He had asked Wu if he could join the lab as a freshman, but was told he wasn't ready. Then after completing an independent research project with Wu in his sophomore year, Heckman was hired.

In the lab, he's helping conduct research on bone marrow cancer. He analyzes snippets of genetic code (a research technique he learned from the graduate students) and, using computer servers hooked up to the Human Genome Project, he tries to match the series of proteins to those already mapped.

Heckman had planned to go to medical school, but working in the lab is giving him new ideas about his future.

"Treating patients is really important, but doctors also need the tools to treat them well, and that comes out of research," he says. "I really like the research part of it and am thinking I'd like to be involved in the tool-making process."

Student Employee of the Year

For Steve Stromski '00, the chance to put on hospital scrubs and walk into an operating room while surgeons removed a cancerous bladder was definitely a highlight of his part-time job at the University.

Steve Stromski '00 at his part-time job in the Medical Center's pathology department, where, along with his more mundane duties, he gets to do sophisticated lab workMaybe even a bigger deal than being named Rochester's Student Employee of the Year for 1998--singled out for the honor from among some 3,000 undergraduates in the College and the Eastman School of Music holding part-time jobs on campus.

A junior biomedical engineering major from Byfield, Massachusetts, Stromski has worked in the Medical Center's pathology department since early in his sophomore year, helping researchers who are trying to find better ways to predict the recurrence of bladder cancer.

The work became a little more immediate when a urology resident escorted him into the operating room.

"I got a little dizzy," Stromski says. "But it was pretty cool."

While the excitement of witnessing surgery is enough to make any science-minded sophomore show up for work, Stromski wins high marks from his supervisors for the way he carries out his more mundane duties, like disinfecting the lab, washing glassware, making reagents, and retrieving specimens from the clinical areas of Strong Memorial Hospital.

"Students are always excited about doing the really cool, high-tech things," says Mary O'Connell, lab supervisor. "But Steve's very happy, very pleasant to work with even when he's doing the yucky jobs that no one else in the lab wants to do."

The job has plenty of high-tech opportunities, too, Stromski says. Since joining the lab, he has learned how to conduct and read tests for genetic markers, called polymerase chain reactions (PCRs), to make photographic images of cell surfaces, and to do other sophisticated laboratory work. In his spare time, he helped write a computer program to streamline an otherwise tedious statistical procedure.

"We were able to leave him alone and let him do projects on his own," O'Connell says. "That's pretty rare for a first-time student."

The Student Employee of the Year program is organized by the National Association of Student Employment Administrators. Each spring, colleges and universities across the country invite campus employers to nominate their best worker. The winner on each campus is then entered in the national competition.

Stromski admits he was surprised to learn he was Rochester's choice and is self-effacing about why he won, preferring to talk instead about what he considers his good fortune in getting the job.

He entered college unsure of his career goals, he says, eventually choosing biomedical engineering because he had an interest both in biology and in scientific equipment like lasers and other optical devices.

He worked in dining services his freshman year because he needed some spending money, but left when he found out about other possibilities on campus.

"But I never thought I'd get into a lab as an undergraduate. I thought it was something only graduate students did."

Copyright 1999, University of Rochester