SURGEON GENERAL'S WARNING:

A Year at Rochester is Beneficial to Your Prescription for Public

Health

In his role as U.S. Surgeon General, David Satcher '72M (Res) was one of

the headliners at Sesquicentennial Weekend. Here are some of the things he has

to say:

By Scott Hauser

In a crisp dress uniform that emphasizes his own physical fitness,

David Satcher '72M (Res) could probably have gotten even the most diehard couch

potato in his Sesquicentennial audience to ask, "How high?" if he had said,

"Jump."

Satcher, the nation's 16th U.S. Surgeon General and a lifelong

public health campaigner, would like everybody to jump more often.

Or jog. Or bike. Or walk.

And he'd like us to drop the smokes, avoid drugs and alcohol,

and pay more attention to what we eat and how much.

When it comes to issuing such stern prescriptions, the founders

of the U.S. Public Health Service may have been on to something in 1870 when

they modeled the cadre of health professionals on military lines, complete with

uniforms.

But Satcher, who honed many of his bedrock ideas about his profession

while completing a residency at Rochester, is not the "drop and give me 20"

type.

"If I have contributed anything, it's that I have been able to

articulate the problems our health system faces in a way that emphasizes the

opportunities that we have and the progress that we can make if we work together,"

he says.

Not exactly spoken like a drill sergeant. Regardless of the uniform,

that's the way Satcher prefers to communicate with his "patients"-whether presidents

or John and Jane Public.

"I would most like to be remembered as the Surgeon General who

listened to the American people and responded with effective programs," is how

he puts it in the literature that he distributes at public speaking engagements.

Sworn in on February 13, 1998, as the nation's highest ranking

doctor, Satcher took command of a job that combines the public health-minded

zeal of a committed physician and the organizational skill of a general, at

least administratively.

The Surgeon General oversees more than 6,000 members of the commissioned

corps of the U.S. Public Health Service, a uniformed cadre of physicians, nurses,

pharmacists, and technicians who are available around the clock to respond to

health crises, and who are, in effect, the troops that the doctor-in-chief directs

in public health battles.

The job also requires setting a health care chart for America.

In his public health roles, Satcher often recalls his experience

at Rochester, which he ranked as his top choice for a residency in 1972 as a

recent M.D. and Ph.D. graduate of Case Western Reserve University.

He was intrigued that Rochester would allow him to combine a pediatrics

rotation within a mixed medicine residency.

But he was sold on Rochester after discovering the Medical Center's

commitment to fostering interaction between Strong Memorial Hospital and neighborhood

clinics designed to work with underserved populations.

"Rochester provided some excellent models in the form of bringing

the community and the hospital together," Satcher says. "It was always a program

that I was interested in, but it became Number One after I visited and really

learned more about what faculty and staff were doing there."

While at Rochester, Satcher worked in a migrant health clinic

and saw patients in newly established community health centers and at Monroe

Community Hospital.

"Rochester is with me everywhere I go," he says, giving special

credit to Medical Center professors T. Franklin Williams, Robert Haggerty, the

late George Engel, William Morgan, and Naomi Chamberlain.

"They had a way of making the house staff feel important," Satcher

says. "And that's not easy to do with residents and interns."

Williams says he remembers Satcher as a knowledgeable young doctor

who had a particularly good rapport with patients.

"I was very much impressed with him at the time," Williams says.

"He was a bright, attentive physician who took a real interest in his patients."

Satcher also was the only black doctor on the staff, says Williams,

who as a former director of the National Institute on Aging is a commissioned

officer (retired) in the public health service-and technically under the Surgeon

General's command.

"I think being a minority may have helped him be sensitive to

the concerns of the outsiders in society, whether they are members of minority

groups, the sick, or the elderly," Williams says. "He saw these important issues

with a broader perspective than most interns or residents at the time."

For his part, Satcher says he was used to being the only African-American

in his class, a distinction that he often had during medical school.

But he says he is grateful that Rochester allowed him to hone

his ideas about race in medicine. While at Rochester, he was encouraged to write

a paper on how race affects the doctor-patient relationship.

Just as racial tension influences the criminal justice system

or other bureaucratic systems involving personal interaction, race is a factor

in how doctors relate to patients, the young resident argued.

His paper and presentation received an award from the Medical

Center, and the paper was later published in the Journal of the American

Medical Association.

"That's the kind of environment that I found at Rochester," Satcher

says.

From Rochester, Satcher went on to the University of California

at Los Angeles, where he received a fellowship to open a community health clinic

in Watts, a predominantly black section of Los Angeles, and eventually became

a faculty member of the UCLA School of Medicine and Public Health and the King-Drew

Medical Center in Los Angeles. He also developed and chaired the King-Drew Department

of Family Medicine.

In 1979, he was named professor and chairman of the department

of community medicine and family practice at Morehouse School of Medicine, based

at the university where Satcher had been an undergraduate.

In 1982, he was appointed president of Meharry Medical College

in Nashville, Tennessee, a post he held until 1993, when he was named director

of the Centers for Disease Control in Atlanta.

He was heading the CDC when President Clinton appointed him Surgeon

General.

As the nation's top doctor, Satcher quickly made use of a highly

visible bully pulpit to wade into the public health issues of the day.

One of his top priorities-eliminating racial and ethnic disparities

in health and the health care system-has roots in Rochester.

While untying the political, technical, social, and cultural knots

that influence how health care is allocated to members of the nation's minorities

may seem intractable, Satcher remains sanguine about the long-term prognosis.

Many of the issues that he wrote about as a medical resident have

been backed up by research during the past quarter century, Satcher says, pointing

to studies that show black males are less likely to be referred to specialists

than white males when they complain of identical cardiac symptoms, or that black

females have the highest rate of breast cancer among American women.

We're looking at this from the standpoint of research now," he

says. "Twenty-six, twenty-seven years ago, I was talking about what I had observed."

He hopes that all sides of the issue can work to improve the situation.

"My interest is in making progress," he says. "I'm not one to

point fingers. If you really want to make progress, then you talk about a problem

that we share -racism, racialism, whatever you want to call it-and we work together

to come up with solutions."

During his three-year tenure, Satcher has emphasized creating

balance in the community health system to tip the scales more in the direction

of preventive medicine and health education.

That includes spending more time and money promoting healthy lifestyles

and ensuring earlier access to the system.

He cites surveys by the World Health Organization that rank the

United States 15th globally in terms of the outcomes of our medical system and

37th in terms of efficiency.

Despite being a world leader in medical technology and research,

the American system is skewed toward treatment rather than prevention, he says.

"As long as we're chasing diseases in their late stages, health

care will never be affordable," he notes.

He also hopes that mental health care is included in the balance,

requiring society to overcome the enduring stigma associated with mental illness.

"We must make it very clear that just as things go wrong with

the heart, the lungs, and the liver, they also go wrong with the brain," he

says.

Satcher's other top priority has been emphasizing the global nature

of most health-care policy directions.

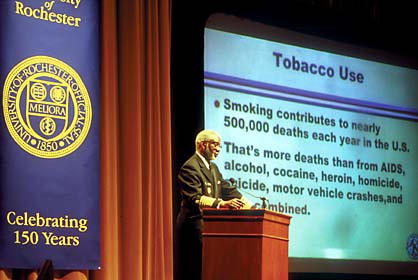

Smoking is a good example of that, he says. Since the first Surgeon

General's warning in 1964, the percentage of Americans who smoke has declined

steadily from 43 percent of the population (including 50 percent of doctors)

to about 23 percent today (and less than 5 percent of doctors).

"We've had a pretty good record of progress," Satcher says.

The Surgeon General's goal has been to reduce the rate another

50 percent by 2010, with particular emphasis on educating children on the dangers

of smoking.

But while the rate goes down in the United States, the percentage

of smokers in developing countries is unchanged and, in many instances, is increasing,

as tobacco companies shift their activities to less regulated economies.

An estimated 4 million people worldwide, including 430,000 in

the United States, were expected to die in 2000 from smoking and its complications,

Satcher says. By 2030, that number is expected to rise to 10 million.

"This has become a global issue and I'm proud that the Surgeon

General's office is taking a major part in addressing it," Satcher says.

The future remains at the heart of Satcher's work, and he is upbeat

and engaging when he outlines his vision of how everyone can have a more healthy

one.

During his visit to Rochester in October as a guest speaker for

the University's Sesquicentennial and the Medical Center's 75th anniversary,

Satcher peppered his talk with jokes about health care and health care policymakers.

After his presentation, he told a story that reiterated his approach

to the importance of preventive health education.

At a ceremony celebrating the 97th birthday of South Carolina

Senator Strom Thurmond, the senator was asked if he thought the guests would

be gathered again for his 98th birthday.

Said the senator: "If you eat right, exercise regularly, and take

care of yourselves, I'll see you then."

Not a trace of the drill sergeant in that prescription.

Scott Hauser's most recent alumni profile for the magazine

was on Edward '66 and Cheryl Neel Mendelson '73 (PhD) in the Fall 2000 issue.

Maintained by University Public Relations

Please send your comments and suggestions to:

Rochester Review.

[an error occurred while processing this directive]

|

![[NEWS AND FACTS BANNER]](/URClipArt/misc/newsfacts.jpg)

![[NEWS AND FACTS BANNER]](/URClipArt/misc/newsfacts.jpg)