|

![[NEWS AND FACTS BANNER]](/URClipArt/misc/newsfacts.jpg) |

|||||||

'ACT'-ing to Ease the Pain of Divorce on ChildrenHelping both children and parents get through the emotional pain of divorce, psychologist JoAnne Pedro-Carroll carries on a Rochester-pioneered approach to mental health care that focuses on reducing the psychological trauma of children. by Christine L. Ridarsky

JoAnne waits impatiently for her ex-husband to bring their 7-year-old daughter, Jesse, home. He is 45 minutes late, and with each minute that passes JoAnne grows more anxious-and angry. She can't help but remember all the times Ernesto has let her down in the past. Finally, he pulls his car into the driveway. The sight of his girlfriend in the front seat adds to JoAnne's rage. She storms out the front door. "Where have you been? You're 45 minutes late!" she yells. "You could have at least called!" "I tried to call, but you must have been jabbering on the phone again," Ernesto retorts. Jesse fidgets and slouches, shrinking into the background. It's almost as if she were trying to make herself disappear. "You didn't send a check this month," JoAnne continues the attack. "You never pay on time. Jesse, don't plan on seeing your father next week because he hasn't bothered to pay his child support. Come on." JoAnne nudges her daughter toward the house. "Bye, Dad," Jesse mumbles over her shoulder. There's no chance for a hug or a kiss.

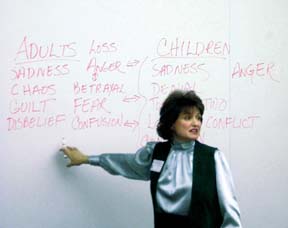

As the classroom of divorcing parents watch the role-playing exercise led by JoAnne Pedro-Carroll '84 (PhD), associate professor of clinical and social sciences in psychology at the University, some are riveted, some fidget, some sit quietly. But all recognize the charged exchange of anger, resentment, and betrayal staged by Pedro-Carroll ("JoAnne" in the scene) and Ernesto Michelucci, a Rochester clinical psychologist, during a late spring counseling session. Playing the role of "Jesse" was a young mother whose parents had divorced when she was young and who herself had recently divorced. Though fictional, the episode brought back stomach-churning emotions. "I felt like I just wanted to crawl under both of your shoes," she told Pedro-Carroll and Michelucci as tears welled up in her eyes. Such pointed-and sometimes painful -lessons on how a marital breakup affects children are the focus of an educational program for divorcing parents developed by Pedro-Carroll, director of Programs for Families in Transition at the University-affiliated Children's Institute (formerly the Primary Mental Health Project). Called ACT (Assisting Children through Transition)-For the Children, the program is a collaboration with the Seventh Judicial District of New York and is designed to help divorcing parents reduce the stress of a family breakup. The success of ACT, along with a program Pedro-Carroll has developed for elementary and junior high school students, has earned the psychologist a national reputation as one of the country's leading experts on the effects divorce has on children and families. "Our preliminary results indicate that parent education programs can be an important step toward achieving healthier family relationships," she says. "We have seen statistically significant decreases in conflict between parents, increases in effective parenting practices, decreases in the likelihood of litigation, and, more importantly, increases in children's healthy adjustment." Originally known as the Parent Education and Custody Effectiveness (PEACE) program, ACT began in 1998. Judges can order divorcing parents to attend, but many choose to participate even if they are not required to. The program is the lastest in a Rochester-pioneered approach to mental health care that emphasizes prevention and early intervention to help children and their families cope with difficult changes in their lives. It's an approach to community and preventive health care that Pedro-Carroll first became interested in more than 20 years ago while working with the Cincinnati Health Department. Part of a team that developed school-based intervention programs for children living in low-income neighborhoods, the Youngstown, Ohio, native read about the work of Rochester's renowned Emory Cowen. Cowen, a longtime professor of psychology and psychiatry, is credited with revolutionizing mental health care through his ground-breaking work in the field of prevention research and practice. (The founder of the Primary Mental Health Project at the University in 1957, Cowen, died last November.) The two began corresponding, and Cowen encouraged Pedro-Carroll to come to the University to pursue master's and doctoral work in clinical psychology. With the encouragement of her husband, Roger Carroll, who sold his Cincinnati dental practice to move to Rochester, Pedro-Carroll completed her master's degree in 1982 and received her doctorate in 1984. While studying with Cowen, Pedro-Carroll noticed that increasing numbers of children were being referred to counseling to help cope with their parents' breakup. Divorce rates had risen sharply in the United States in the 1960s and 1970s, and children appeared to be paying the price. "It seemed to me that what children really needed was a safe, supportive place, where they could share their experiences and learn skills to help them cope with all the changes in their lives," Pedro-Carroll says. In 1983, Pedro-Carroll developed the Children of Divorce Intervention Program as part of her doctoral dissertation. The school-based program is designed to provide social support for children while teaching them skills for dealing with stress. "Children tend to think they're alone," says Diane Wardlow, a social

worker and coordinator of the program at Jefferson Avenue School in the Rochester

suburb While adults may have trouble expressing their emotions, children may have an even more difficult time communicating their distress, Pedro-Carroll says. Younger children may become clingy, constantly demanding attention. Or they may regress to behavior they had given up, such as sucking their thumbs or speaking baby talk. Older children may try to hide their pain. Signs that they are troubled may include a drop in their school grades or, for teenagers, engaging in risky sexual behavior. Serving students in kindergarten through eighth grade, the Children of Divorce Intervention Program emphasizes communicating effectively, managing anger, and solving problems. One of the first lessons is helping children recognize which issues they have control over and which they do not. The fact of their parents' divorce, Pedro-Carroll notes, falls in the latter category. The goal is to get children to "focus on disengaging from problems they cannot solve and engaging in those they can," she says. Children meet during school about once a week in groups of between four and eight, depending on their age. Group leaders use puppet play and games to help younger children recognize and deal with their feelings. In charades, for example, children act out a feeling and have the others guess what it is. Older children may produce a mock talk show in which they pose questions about divorce to a panel of peers who serve as "experts." During the past 18 years, several studies have indicated that children who have participated in the program have smoother adjustments in their home and school life than students who have not taken part. Used by more than 50 Rochester area schools, the program has served as a model across the United States and in other countries. Such success has garnered Pedro-Carroll national recognition: Last summer she received the American Psychological Association's Distinguished Contributions to Public Service Award and the Association for Family and Conciliatory Courts' Stanley Cohen Distinguished Researcher Award. Robert Emery, director of the Center for Children, Families, and the Law at the University of Virginia, says Pedro-Carroll's sensitivity to her clients' needs, combined with her commitment to documenting results, sets her apart from most researchers in the field. "Many psychologists have one of these qualities, but, unfortunately, few have both," he says. "JoAnne's clinical skills lead her to develop creative and insightful treatments that families appreciate both for the program's effectiveness and for its sensitivity to their individual concerns." That kind of sensitivity and documentation has shaped Pedro-Carroll's most recent work with separating parents. Realizing that how children fare after a divorce is directly related to how their parents handle the situation, Pedro-Carroll hit upon the idea for ACT. New York State Supreme Court Justice Evelyn Frazee, who co-chairs ACT, says one of the first cases she presided over after joining the bench convinced her to team up with Pedro-Carroll. "The parents were in extremely high conflict, to the point that the 12-year-old tried to commit suicide," she says. "When you see that, you realize there has to be a better way to do this." Frazee says divorcing parents can "become very focused on what's happening to them and sometimes lose sight of the children. I think this program helps them refocus." Sheldon Boyce, a father of three who attended the program three years ago, agrees. "You have to do your utmost to remove your emotions from the decision-making process," he says. To do that, Pedro-Carroll recommends that ex-spouses redefine their relationships using a business model. "I think for all of us there are times when we have to work with someone we might not get along with. Yet, if we care about the outcome of a project we stay focused on the goals to succeed," Pedro-Carroll says. "It's a model that many parents report is helpful to them because it takes the emotion out and keeps them focused on the needs of their children." During last spring's session, she and Michelucci, who is a regular presenter in the program, demonstrated how the scenario with "Jesse" may have been different if one or both of the parents had followed the model. In an ideal situation, they pointed out, Jesse would have been allowed to say goodbye to her father and go into the house before her parents talked about issues involving their divorce. "The key point there is we want to prevent Jesse from getting caught in our conflict," Pedro-Carroll says. She and Michelucci also offered suggestions for parents to reduce conflict in their relationships with ex-spouses. "The 'golden rule' of communication is to take 'you never' and 'you always' out of your vocabulary," Michelucci told the group. "Instead, we want to use a technique called 'I messages.'" For example, in the role-playing exercise if JoAnne had said, "I get worried when you're late" instead of "You are always late," the conversation may have gone a little smoother. Another tactic parents can use to avoid angry confrontations in front of their children is to schedule meetings on neutral ground away from the children. Pedro-Carroll suggests setting an agenda for the meeting-and sticking to it. Bridget Fitzgerald, a 46-year-old mother of two who participated in the program last fall, says she finds such an approach helpful. She says she was very angry when her 23-year marriage ended. "It helped me realize, 'OK, you're mad, get over it,'" she says. Now, "I try to handle everything more like you would handle it in a business situation. You're not going to use inflammatory language or push buttons just because you know where those buttons are." It's a change she says her children appreciate: "Both my children have told me it's so much easier not hearing conflict in the house." Fitzgerald's positive reaction to the program is typical. Although Pedro-Carroll has yet to study the long-term effects of the program, a one-year follow- up survey of parents who participated indicates that 95 percent believe the information they learned helped them and their children. That's just the type of thing Pedro-Carroll likes to hear. "I am grateful everyday that I get to do work I love and work that is gratifying," she says. Christine L. Ridarsky is a Rochester-based freelance writer.

Maintained by University Public Relations | ||||||||