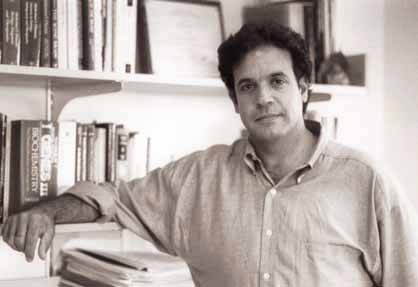

RUDOLPH TANZI '80

2001: Decoding Alzheimer's

The question sounds like the setup for an old Vaudeville joke: How does a 22-year-old

keyboardist fresh from college at Rochester in 1980 get to be one of the world's

top experts on the genetics of Alzheimer's disease?

Not practice, practice, practice exactly.

But for Rudolph Tanzi '80, professor of neurology at Harvard Medical School

and director of the Massachusetts General Hospital's Genetics and Aging Research

Unit, his 20-year trajectory from aspiring musician to groundbreaking researcher

illustrates some of the human drama-including humor-that lies behind most scientific

endeavors.

It's an aspect of the scientific calling that shines throughout his highly

regarded book, Decoding Darkness, documenting his efforts to pinpoint

some of the genetic machinery behind the debilitating neurological disease.

"One of the goals of the book was to give people the human side of science,"

Tanzi says. "Research doesn't always follow a nice, clear, sterile line

from inspiration to discovery."

Published in November 2000, the book, written with science journalist Ann Parson,

is part biography, part introduction to molecular genetics, and part initiation

into the sometimes cutthroat world of high-stakes medical research.

The book also has a strong tone of detective story, beginning with Tanzi's

first summer out of Rochester-when he was trying to support himself playing

music-and following him as he rekindles his interest in genetics research. He

soon begins tracking the elusive villain that many scientists have identified

as the culprit behind Alzheimer's, amyloid beta protein.

As a reviewer in the New England Journal of Medicine described the book:

"You do not have to be a geneticist or a neurologist to enjoy Decoding

Darkness. The story is invigorating, the progress is fantastic, and the

writing is lively."

Tanzi has contributed several milestones to recent progress on Alzheimer's.

His lab was the first to find the genetic link for the precursor to amyloid

beta protein on chromosome 21, and he created the first genetic map of the chromosome.

Of the six genes implicated in Alzheimer's, Tanzi and his lab have identified

or were closely involved in the discovery of five.

Not a bad career's worth of work, especially given that Tanzi walked into his

first Mass General lab in 1980 in response to a bulletin board ad. He had been

working as a musician in Boston and Providence and was looking for a steadier

paycheck.

"In the fall of 1980, I decided I needed a real job," he says.

As luck would have it, the scientist looking for help was a 26-year-old researcher

named Jim Gusella who had set himself the task of trying to find the genetic

markers for Huntington's disease.

"That sounds totally mundane now, but at the time people thought it was

totally crazy," Tanzi says.

With that goal accomplished, Tanzi set his sights on other targets, including

Down Syndrome and Alzheimer's. Along the way, he earned a Ph.D. in molecular

biology from Harvard and rose in the tanks of the lab.

A history and microbiology double major at Rochester, Tanzi was instrumental

in getting Gusella's lab up and running. As a microbiology major, he had spent

many hours in Medical Center labs.

"Coming out of Rochester, I knew how to do things that the majority of

undergraduates probably never learn how to do," Tanzi says. "I knew

enough from my training to set up (Gusella's) lab."

While at Rochester, too, he continued his interest in music, taking courses

at the Eastman School and playing in jazz and rock bands on the River Campus.

He continues to compose and perform music, and he maintains a Web site, called

the "Quiet Mind Project" (http://artists.mp3s.com/artists/34/rudy_tanzi.html)

that features his work. The site has recorded more than 40,000 hits and several

times that many downloads.

"It's a hobby," Tanzi notes.

As for his "real job," Tanzi, like many Alzheimer's researchers,

marvels at the progress scientists have made in unlocking the mystery of the

disease in the past two decades, especially in pursuing amyloid protein.

"I think we're going to see a dovetailing in the next five to 10 years

of reliable genetic testing along with an effective drug treatment," Tanzi

says. "We need to continue to attack the disease with a strategy of early

prediction, early prevention, and effective therapy."

He cautions that progress on the genetic front will require a corresponding

effort to protect the medical privacy of people who may be at greater risk for

the disease, but he's confident that the disease-which will afflict an estimated

14 million Americans by 2050 if no effective treatments are found-will eventually

yield to science.

"If we stay on this course of solving the genetic puzzle behind Alzheimer's

and if we keep trying to hit the amyloid protein target, we have a significant

chance of reducing the occurrence of Alzheimer's."

1980: Human Side of Science

Rudolph Tanzi was a student in some of the first classes taught at Rochester

by Theodore Brown, now chair of the Department of History and professor of community

and preventive medicine and of medical humanities.

One of those courses was a freshman preceptorial on the scientific revolution

wrought by evolutionary pioneer Charles Darwin. Brown says the goal of the course,

like nearly all of his courses dealing with the history of science, was to show

that science-like music or art-is a human endeavor.

It's a lesson that apparently sunk in for Tanzi, whose Decoding Darkness

recounts the human emotion behind efforts to understand Alzheimer's disease.

Says Brown: "If there was one message that I hoped students took away

from that course it was that even the greatest scientists have times in which

they are blocked and feel frustrated, but that the greatest discoveries may

come at times when they least expect them."

Scott Hauser

Maintained by University Public Relations

Please send your comments and suggestions to:

Rochester Review.

[an error occurred while processing this directive]

|

![[NEWS AND FACTS BANNER]](/URClipArt/misc/newsfacts.jpg)

![[NEWS AND FACTS BANNER]](/URClipArt/misc/newsfacts.jpg)