![[NEWS AND FACTS BANNER]](/URClipArt/news/titleNewsFactswide.jpg) |

||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||

The Doctorate Is CallingRochester has long been known as a place that develops future generations of academic leaders. Here's a look at a small sample of the next generation. By Scott Hauser

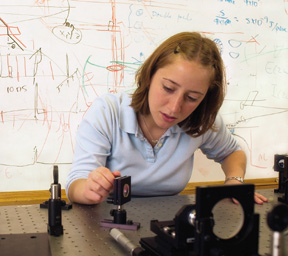

Amy Ruschak '02 moves around the two-room, glass-filled laboratory in the basement of Hutchison Hall with the alacrity and confidence of the fully tenured professor she plans to one day become. The chemistry major has spent a lot of time in the lab-"If I'm not in class, I'm here," she says, taking her position at the low bench-where she works under the supervision of chemistry professor Douglas Turner and the graduate and postdoctoral students in his group. Surrounded by test tubes, pipettes, and sequencing gels, Ruschak already has received a well-rounded education in the life of a faculty member at a research university. Sure, there are the mundane tasks and routine assays, but she's also conducted some technically accomplished biochemical experiments that have spurred an interest to continue searching for the keys to the molecular biology of RNA and other cellular structures. An admitted math-and-physics-phile from way back, Ruschak, has found her true calling in biophysical chemistry. "When I started in this lab, I never thought that I'd want to do this," she says. "But I have discovered that I want to do this for the rest of my life.

"This research has put everything into perspective." That perspective, sharpened by the opportunity to work for four years with a prominent researcher, is so crystalline that Ruschak has her future mapped out as sequentially as one of the RNA strands she studies: Get a Ph.D. and embark on her own research and teaching career at a university. If all goes according to plan, she, too, will set up her own lab, where, in turn, she will likely instill another generation of students with the thrill of scholarship. Ruschak, who was selected as one of 75 Howard Hughes Fellows from across the nation to continue her studies in science, begins the first phase of that career this fall when she enrolls in graduate school at Yale University. While the process of developing future generations of scholars lies at the heart of all research universities, Rochester seems to have an uncommonly deft touch in awakening that inspiration. According to the most recent edition of a regularly updated report by Franklin and Marshall College that keeps track of where Ph.D.'s in 233 universities and colleges across the country received their undergraduate education, Rochester ranks ninth in the percentage of undergraduates who go on to receive doctorates. Across disciplines-the humanities, the sciences, and in all fields-Rochester ranks among the top 10 in the percentage of students who receive their Ph.D.'s, a crossdisciplinary sweep shared only by Chicago, Harvard, Princeton, and Yale.

All told, more than 30 percent of Rochester undergraduates go on to receive the graduate degree that is considered the final one in their field. In addition to the 10 percent who receive doctorates, another 10 percent earn law degrees, and about 12 percent go on to get medical degrees. In a related study, Bruce Jacobs, dean of graduate studies at the University,

has identified more than 1,000 graduates who have earned academic degrees from

Rochester and who are now on the faculty at all of the nation's top 25 colleges

and universities, as measured by the National Research Council and U.S. News

Provost Charles E. Phelps says Rochester has long had a record of inspiring future academic leaders because the University has long emphasized close collaboration between faculty and students, the kind of culture of curiosity that thrives at small, liberal arts colleges (which, historically, also have had a relatively large percentage of students go on to get Ph.D.'s). But Rochester adds the extra ingredient of plenty of opportunities for undergraduates to conduct research with faculty members who are at the top of their fields, says Phelps. "At Rochester, it's easy to spot the bright students in your classes and then call them in to talk about their future plans," he says. "But there also are more opportunities for you to get those really bright students involved in the projects that you are doing." Phelps says such a moment was life changing for him. "I had a professor call me aside and ask, 'Have you ever thought about getting a Ph.D.?'" the noted health care economist says. "Until then, it had not occurred to me to go on to get a doctorate. It's like a good deed: I promised myself that I would do that when I was a faculty member."

"I couldn't do that very easily if I had 150 or 200 students in every class," he says. "In many ways, we use our smallness as our strength." Turner, who supervises Ruschak, agrees, noting that an unofficial motto of the chemistry department is, "We develop people from freshmen to faculty." "Amy is special, no doubt about it," says Turner. "But she has been able to draw on all the things that Rochester has to offer, such as working in collaboration with Tom Eickbush in the Department of Biology. It's easy to have that kind of collaboration here." Turner says he usually has at least one undergraduate working in his lab, and he says it's gratifying when such students later tell him that the experience has inspired them to get a Ph.D. "I've had some outstanding students," Turner says. "I have enjoyed

watching them develop over the course of their time in my lab, and as they've

gone on Emil Homerin, chair of the Department of Religion and Classics, says he's looking

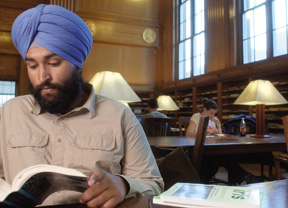

forward to watching the professional career of Rahuldeep Singh Gill '02, a religion

major and Take Five Scholar who is headed to the University of California at

Santa Barbara this fall to pursue Ph.D. studies focused on India's Punjab region. "Rahuldeep is among the very best students to graduate from this department," Homerin says. Gill says he arrived on campus planning to become a different kind of doctor-a medical doctor.

Although he took the science courses that he would need to get into medical school, he was so intrigued by his courses in the humanities that he eventually altered his goal about what kind of terminal degree to pursue. Religion is the "most interesting" field to study, Gill says, because it touches on all aspects of the human condition-human nature, society, literature, science, and art. "Studying religion gives you access to so many different realms," Gill says. He crafted a Take Five project that allowed him to spend a fifth year at Rochester to study some of the same questions from a different perspective. His project, "Politics, Power, and the People," focused on political science. "The cool thing about combining religion and political science is that the social sciences have a very different way of approaching questions and coming up with answers than the humanities do," Gill says. "Having those different sets of skills-religion, political science, and even the pre-med-has helped me fulfill the goal of a liberal arts education that the College takes so seriously." Gill says he sees teaching as his ideal career and credits his own teachers as role models. "If I could be half as good as some of the professors in the Department of Religion and Classics, I'll be doing very well," Gill says. Loren Cerami '02, an optics major, also hopes to make a difference as a teacher and a scholar, particularly by encouraging more women and minorities to take an interest in engineering and science. One of only 10 students chosen in the United States to receive a prestigious Churchill Scholarship this year, she plans to complete a one-year master's program at Churchill College at Cambridge, and then return to pursue a Ph.D. in optics, physics, or engineering. It's a goal that has evolved for Cerami, who also was a captain of the women's soccer team and was president of the engineering honor society Tau Beta Pi. "You take one class, and you know that's only scratching the surface," Cerami says. "You know there is more that you want to learn." Embarking on that commitment to learn ever more is not a career decision to be taken lightly. At a minimum, receiving a Ph.D. requires at least four more years-and perhaps more-of advanced, often arduous, coursework, a substantial piece of new scholarship, and admittance to the field by colleagues. And, while recent national reports indicate that the number of students pursuing doctorates is slowly climbing after a slumping year in 1999-2000, there are few indications that the job market for Ph.D.'s-especially in the humanities-will be anything but tight for the next several years. Camber Warren '02, political science major from Davis, California, who plans to pursue his doctorate in political science at Duke University this fall, is not deterred. He's wanted to become a professor ever since he arrived on the River Campus as a neuroscience major. It's only the subject that has changed. "One of my professors says it takes a lot of ego to go into a field like this because nothing is guaranteed," Warren says. "You have to have a certain amount of confidence that this is something you will be good at. And I am fairly confident that I will be good at it." Warren, who also earned All American honors as a member of Rochester's debate team, is used to researching ideas, developing them, and putting them to the test among colleagues. No matter how he looks at it, he can't shake the appeal of doing that for a living. "This is the only field I'm aware of that will pay me to read about interesting things, and then to write about them," he says. Richard Niemi, director of undergraduate studies in the Department of Political Science, says interest among the department's students in pursuing doctorates seems to be increasing. "It's gratifying to see students do well -in whatever they want to do," Niemi says. Given the job market for Ph.D.'s in the social sciences, the department is cautious about sending too many students to Ph.D. programs, Niemi says. Warren understands that. "If money were my central concern, this would not be something that I would be pursuing," Warren says. "It matters more to me that I will be doing something I really love." Karl Wright '02, a history major and Take Five Scholar who begins his Ph.D. work at the University of Illinois this fall, also is intrigued by the challenge. "Getting a Ph.D. is one of the highest intellectual accomplishments you can achieve," Wright says. "If you're going to undertake something like graduate school, it doesn't make any sense to do it half way." Wright, who emphasized African-American history as an undergraduate, plans to study Chinese politics at the Urbana-Champaign campus. He credits faculty in the history department and the staff of Rochester's chapter of the Ronald E. McNair program, a national program designed to encourage underrepresented and first-generation students to pursue graduate education, with inspiring him to study for a doctorate. "My professors have always encouraged me to have ambitious goals," Wright says. He hopes to repay the inspiration with his own students. Scott Hauser is editor of Rochester Review. Maintained by University Public Relations |

||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||

| ©Copyright 1999 — 2004 University of Rochester | ||||||||||||||||