Features

Abso-LUTE-ly Fabulous

|

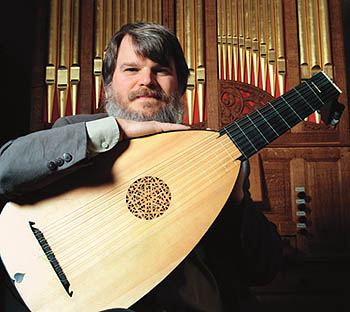

The music of 400 years ago has a lot to teach about contemporary classical music, says master lutenist Paul O'Dette, who will direct a new graduate program in early music at the Eastman School. By Scott Hauser. Photography by Elizabeth Torgerson-Lamark.

As with many teenagers growing up in the late 1960s, Paul O’Dette played out his mild notions of rebellion by picking up a guitar and joining a rock ’n’ roll band.

But when it came time to make a musical statement, the young man from Columbus, Ohio, chose an instrument that electrified not the gap between a generation of music fans, but one that has enchanted music lovers for centuries—the lute.

“It was love at first chord,” says O’Dette, who has directed early music at the Eastman School since 1976. “The first time I heard the sound, I was instantly transported to another time and place. I was completely captivated.”

And while some might argue that the lute’s “time and place” ended about the same time as the reign of Queen Elizabeth I, O’Dette has, for the past 30 years, been making sure that the music of what was once the most popular instrument in Europe continues to resonate into the future.

“When most people think of virtuosi on the Renaissance lute, they think of O’Dette,” says Douglas Alton Smith, the author of A History of the Lute From Antiquity to the Renaissance.

And beginning this fall, O’Dette adds to his roles as teacher, scholar, and performer when he oversees the Eastman School’s new master’s and doctor of musical arts degree programs in early music. Students in the program will study the performance, music, methodology, and the history of the lute as well as other instruments from the Middle Ages, Renaissance, and Baroque periods of European music.

Eastman is joining only a handful of music schools across the country to offer a graduate-level program in early music, says Marie Rolf, professor of music theory and associate dean of graduate studies, but she says interest among students, faculty, performers, and audiences has been on the rise since the late 1980s.

The new program—officially known as the program in Early Music with an Emphasis in Lute and Historical Plucked Instruments—fits well with Eastman’s recent initiatives in organ and complements the interests of many faculty in performance and musicology, she says.

“It’s a very rich environment for early music,” Rolf says. “We have unparalleled resources in the Sibley Music Library and among our faculty.”

And while the program is expected to remain small—O’Dette expects no more than six lute students and up to a dozen total, including other instruments—the ideas behind the study of early music have had a large influence on contemporary classical music and performance, he says.

Guided by the principle that music sounds best when performed in ways that mirror how composers meant it to be performed, the study of early music is helping re-invigorate interest in classical music, O’Dette says, because it requires scholars and performers to think about music—even the most familiar repertoire pieces—in new ways.

“By going back to the original sources and really appreciating what composers and performers were trying to accomplish—this can’t help but breathe new life and new blood into the concert hall,” says O’Dette, who also directs the biennial Boston Early Music Festival and directs Eastman’s baroque ensemble Collegium Musicum.

Rebecca Harris-Warrick, professor of musicology at Cornell University, who collaborated with O’Dette last fall in a production of Jean-Baptiste Lully’s Le Carnavale Mascarade, says O’Dette is the rare combination of top-flight performer and first-class academician.

“When he sleeps—I don’t know,” she says. “He’s a fantastic technical player, but he also is a researcher who does the kind of work I do as a musicologist.”

When he is not performing a schedule that includes as many as 80 dates a year, O’Dette can often be found scouring European libraries and archives for long-lost masterpieces of lute music, deciphering archaic notation schemes, and recording the transcriptions. He estimates there are as many as 150,000 pieces of lute music, much of which hasn’t been performed in 400 years.

His recording of the complete works of Renaissance composer John Dowland was named one of the top-five all-time best recordings in a survey by the Lute Society of America and won France’s Diapason d’Or de l'Année, also known as the French Grammy.

“One has to be part archeologist, part organologist, part musicologist, part linguist, part performer, part entertainer,” says O’Dette. “It’s a lot of things.”

Scott Hauser is editor of Rochester Review.