Features

Treasures Abound

As the Sibley Music Library celebrates its centennial, Review takes a peek

at some of the rare and one-of-a-kind jewels that make it special. By Scott

Hauser. Photography by Kurt Brownell.

Sibley Music Library Timeline

The Sibley Music Library was founded with a modest, but powerful, goal: Share the joy of music by lending scores to local residents who were interested in learning music in their homes or in playing public performances.

One hundred years later, the library at the Eastman School of Music is still open to the public, and the goal of sharing the joy of music remains just as powerful. But the library’s reach extends far beyond the parlors and parade grounds of Rochester.

Special Exhibits

Now one of the nation’s preeminent music repositories, the library also is home to one of the most highly regarded collections of rare and unique scores, manuscripts, books, and other pieces of music history.

Housed in a climate-controlled, secure room known as “the vault,” the musical treasures gathered in the Ruth T. Watanabe Special Collections draw scholars, students, and musicians from all over the world.

In recognition of the library’s centennial celebration in October, Review asked David Peter Coppen, special collections librarian and archivist at Sibley, to put together a “hit parade” of sorts, featuring a sample of some of the most significant pieces in the collection.

Some selections are one-of-a-kind, some are uncommon examples of the library’s breadth, and some represent Coppen’s appreciation for and familiarity with the collection as an archivist, pianist, and teacher. But all make you appreciate the joy of music.

Number One

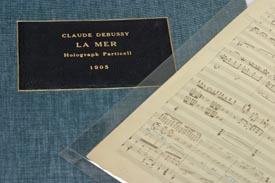

La Mer: Trois esquisses symphoniques pour orchestre

|

A 1905 autographed copy of the original “short score” of La Mer by composer Claude Debussy is the Special Collections department’s most celebrated holding, based on the high regard that researchers, performers, and students have for the manuscript, and on the cold facts of the number of requests to see it. No matter what topic originally brought researchers to Sibley, they often ask, “Do you mind if I look at La Mer?” Coppen says. The draft, acquired in 1929, is a detailed sketch for what would become the full orchestration of Debussy’s masterpiece.

Noteworthy detail: The manuscript is dated with extreme precision on the last page: “Dimanche 5 Mars/1905//Claude Debussy a 6h du soir (Translation: “Sunday, March 5, 1905, at 6 o’clock in the evening”), and a discerning viewer can see that an inscription near the date has been blotted out (presumably before the library acquired the manuscript). After visiting conductor Pierre Boulez asked about it in 1970, the page was analyzed at the Medical Center, and the inscription deciphered as a note to Emma Bardac, who would become Debussy’s second wife: “Pour la p.m. (petite mienne) dont les yeux rient dans l’ombre.” (“For my little one whose eyes sparkle (with happiness) in the shadows.”)

Number Two

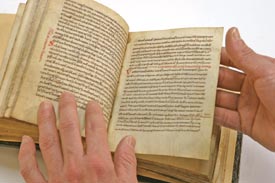

The Reichenau Codex, now known as the “Rochester Codex”

|

Written between 1073 and 1103 in southern Germany, the “Rochester Codex” is a compilation of Medieval European treatises on the arts, including one on music by Hermanus Contractus, one of the premier German theorists of the Middle Ages. The codex is considered one of the earliest complete manuscripts about the science of music available in the United States.

Noteworthy detail: The oldest item in the collection, the codex was purchased at an auction in Berlin in 1929, partly in response to library benefactor H. W. Sibley’s urging, “Buy something we can talk about.”

Number Three

Universal Edition/Kurt Weill Archive

|

Placed on deposit at the library by the European music publisher Universal in 1997, the Weill collection includes eight boxes of manuscripts and other materials chronicling the German composer’s work. “It’s a veritable magnet for researchers,” Coppen says. Highlights include a score of Dreigroschenoper, or The Threepenny Opera, composed by Weill with libretto by Bertolt Brecht. As with many of Weill’s works, the score, dated August 23, 1928, was emended so many times by the composer that historians are unsure what state the opera was in on opening night.

Noteworthy detail: Among those who have marked the score were American composer Marc Blitzstein and conductor Leonard Bernstein, who used the manuscript to mount an English language performance at Brandeis University in 1952. Blitzstein’s adaptation was premiered on Broadway in 1954, with Weill’s widow, the actress Lotte Lenya, reprising her role of Jenny from the original production.

Number Four

Regenlied, opus 59, no. 3 from Acht Lieder und Gesänge, opus 59, by Johannes Brahms

|

The six pages of “Rain Song,” a composition for piano and soprano, is the only known complete copy of the work by the 19th-century composer. “This is my personal favorite,” says Coppen, a pianist. The song’s main theme was later used by Brahms in the third movement of his Violin Sonata no. 1 in G major, opus 78, which he composed in 1878 and 1879.

Noteworthy detail: Brahms was reported to have given a second copy of the song to Clara Schumann, the widow of composer Robert Schumann, but that manuscript is now presumed lost.

Number Five

Die Kunst der Fuge, or The Art of Fugue, by Johann Sebastian Bach

|

One of five first editions of Bach compositions housed in the library, The Art of Fugue, acquired in 1928, is the most analyzed. “Scholars are always keen to study first editions for the secrets they might reveal,” Coppen says. The didactic work expounds on Bach’s ideas of fugue, a composition in which one or two themes are interwoven and played against each other throughout the work.

Noteworthy detail: The intricate line drawings of pastoral scenes and fleur de lis that fill out the pages are eye-catching but represent a misjudgment by the printer. Failing to plan accordingly for the space needed for the musical engravings, the printer filled up the remaining white space with other embellishments.

Number Six

Symphony no. 2, opus 30, ‘Romantic,’ by Howard Hanson

|

One of nearly two dozen autograph manuscripts deposited in 1949 on the 25th anniversary of Hanson’s appointment as director of the Eastman School, the symphony was commissioned by Serge Koussevitsky for the Boston Symphony Orchestra’s 50th anniversary. Widely considered the composer’s masterpiece, Hanson’s Romantic is “like the Fifth Symphony is to Beethoven,” Coppen says. “It’s the Number One bestseller.”

Noteworthy detail: The manuscript includes annotations by Arturo Toscanini, who conducted the symphony’s New York City premiere.

Number Seven

Masses of Josquin des Prez

|

Acquired in 1929, the incomplete set of “part books” of the Masses by the French composer are believed to date from 1514–1516, when they were printed by the Italian printer Petrucci at Fossombrone, Italy. The library is the only U.S. library to hold Fossombrone editions of the part books.

Noteworthy detail: Petrucci devised and perfected a printing process known as “multiple impression,” in which each sheet of paper was passed through the printing press two or even three times. Although complex, time-consuming, and laborious, the process ensured an alignment and well-spaced clarity not achieved by other publishers of that day.

Number Eight

Manuscripts of various sonatas by Giuseppe Sammartini

|

Gathered as a collection in 1760, some of the pieces by one of the best-known composers for oboe remain unpublished. “Any time you have an unpublished manuscript—and therefore unique material—that’s the kind of thing libraries are interested in owning,” Coppen says of the 1929 acquisition.

Noteworthy detail: In 1999, a graduate student from the University of Western Australia identified the collection as the work of three different hands, based on the penmanship of the various pieces.

Number Nine

Theoretical treatises

|

The vault holds original imprints of works by such renowned theoretical masters as Giovanni Maria Artusi (c. 1540–1613), Pietro Aaron (c. 1480–c. 1550), Johann Nikolaus Forkel (1749–1818), Johann Joseph Fux (1660–1741), Vincenzo Galilei (d. 1591), Heinrich Glarean (c. 1488–1563), Franchinus Gaffurius (1451– 1522), and Johann Mattheson (1681–1764). In many cases, translations or facsimile editions are held in the library’s general stacks. “It’s possible to study the entire history of music printing in our library alone,” says Coppen. “It’s a stellar class of materials.”

Noteworthy detail: The earliest such work in the vault is by Franciscus Niger (1452–1523), an Italian theorist and humanist. The edition includes five monophonic musical settings printed from woodblock, representing the earliest known examples of printed notation in which each note has a specific time value.

Number Ten

Music for lute, viheula, and guitar

|

Acquired over the past 75 years, the “family” of holdings includes six manuscripts for lute which are cited in the scholarly resource RISM (Répertoire Internationale de Sources Musicales). Particularly noteworthy is a manuscript titled “My Lord Danby his book,” acquired in 1930. The anthology was written for William Henry Osborne (1690–1711), who had inherited the title of Earl of Danby. Lord Danby was a proficient lutenist who died from smallpox a few days before his 21st birthday.

Noteworthy detail: Scored as tablature, a method for indicating how to play chords and notes across the strings of a lute, the manuscript includes transcriptions of Handel, whose work is considered difficult to play on the lute.

Number Eleven

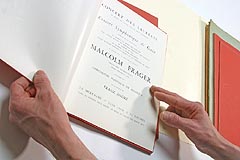

The Malcolm Frager Collection

|

A prominent American pianist and Schumann scholar who died in 1991, Frager was an inveterate documenter of his life and work. The collection includes letters, scores, reviews, contracts, publicity materials, and photographs as well as manuscripts and rare imprints that Frager collected.

Noteworthy detail: Among the collected artifacts are newspaper clippings from Pravda and other Soviet newspapers. Invited by Soviet officials, Frager was one of the first artists to tour the former Soviet Union after Van Cliburn won the Tchaikovsky Competition in 1958.

Number Twelve

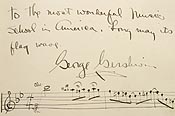

Operatic holdings

|

The library got off to a strong start as one of the nation’s top repositories for operatic works—including full orchestral scores, piano-vocal scores, and solo piano transcriptions—thanks in part to the 1923 acquisition of the working library of French theater critic and scholar Arthur Pougin. The collection has only grown since and now includes such notable items as three piano-vocal scores owned and used by the Covent Garden stage manager (Mozart’s The Magic Flute; Puccini’s La Bohème; and Wagner’s Die Walküre); a copy of the first published full score of Richard Wagner’s Tannhäuser, for which the composer himself etched the image for the lithographing process; and a copy of the first edition of the piano-vocal score of George Gershwin’s Porgy and Bess, signed by Gershwin, librettist Du Bose Heyward, lyricist Ira Gershwin, and producer Rouben Mamoulian.

Noteworthy detail: The vault is home to a substantial cache of rare editions of nine operas by Puccini. That includes a publisher’s proof copy of Madame Butterfly that shows Puccini’s corrections as the score was about to be printed.

Sibley Music Library Timeline

1904: Founded by Hiram Watson Sibley, an heir to the Western Union fortune. Intended “For use by all the music-lovers of Rochester,” the library began as a lending library to provide music scores to Rochesterians. Within a few years, it held about 2,000 pieces. Its first home was in the University’s Sibley Hall on the Prince Street campus.

1921–22: Moved to Eastman School. By 1921, the collection was approaching 10,000 items. Barbara Duncan named director. Duncan oversees the library’s first era of prominence. The library adopts the Library of Congress classification system, leading the rest of the University’s library system to follow suit.

1937: Library moves to new building at 44 Swan St.

1942: Given the extent and value of the holdings, the Board of Trustees votes to discontinue the practice of allowing the public to check items out of the library. But the library remained open to all visitors, a practice that continues today.

1946: Duncan retires and Ruth Watanabe ’52E (PhD) is named director. Given the charge by school director Howard Hanson, “You will buy everything, and I mean everything,” Watanabe introduces the practice of subscription buying from music publishers and other innovations that not only increase the library’s holdings, but also ensure its prominence as an archive. The department was renamed in Watanabe’s honor in 1995.

1947: The collection includes about 55,000 volumes. 1962: The collection includes about 120,000 volumes of books and music, 25,000 uncataloged songs, sheet music, and pamphlets, about 21,000 78–r.p.m. and 12,000 33–r.p.m. recordings, microfilms, microcards, and manuscripts. 1976: Building at Swan Street renovated.

1984: Watanabe retires. Under her leadership, the library’s book and score collection had nearly doubled from 1962. Mary Wallace Davidson named director.

1989: Library moves to its current home at Eastman Place.

1999: David Peter Coppen named special collections librarian and archivist. 2000: Daniel Zager appointed director.

2004: The largest academic music library in the nation, Sibley Library’s holdings include about 336,000 books and scores and 78,000 recordings.

Special Exhibits

|

A. Eastman School of Music Guest Book. In 1923, then library director Barbara Duncan suggested to George Eastman that for $35 a Buffalo stationer could supply the library with a specially made guest book. The book has become a personalized “Who’s Who” of the music world over that past 80 years, featuring brief notes—often quite literally in the form of bars of music—from, and the signatures of, George Gershwin, John Philip Sousa, Aaron Copland (who signed three times), and John Adams, among others.

B. A Willie Stargell Louisville Slugger. After teaming up with the Eastman Philharmonia as the narrator for the debut of Joseph Schwantner’s “New Morning for the World,” the then newly retired Pittsburgh Pirate presented the orchestra with a signed commemorative baseball bat that’s now housed among the special collections.

C. “Space: The Final Frontier.” The vault is home to several items representing the professional and personal papers of Alexander Courage ’41E, a prominent composer for television and movies. Among the highlights: The library keeps a reproduction of Courage’s score for Star Trek’s main theme.

D. Letters. With a collection of more than 1,000 letters, the library offers scholars rare glimpses into the lives of composers and performers. The collections include the correspondence of Carl Czerny, a 19th-century Austrian composer who’s best known for his exercises for piano students that are still used today. The library also has 59 letters to or from Berlioz as well as letters by Wagner, Copland, Debussy, and others.

E. Fischer Archive. In 1999, the library became the repository for the music publisher Carl Fischer, a collection of scores and manuscripts that spanned more than 400 shipping crates when it arrived. “As soon as word went out that Eastman had acquired the archive, the inquiries started to roll in,” Coppen says.

Scott Hauser is editor of Rochester Review.