Alumni Gazette

Being There

A medical professor uses his camera to document the work of a small group of student volunteers after September 11. By Barry Goldstein ’81M (MD), ’82M (PhD)

|

|

|

|

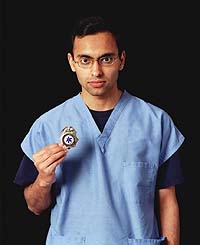

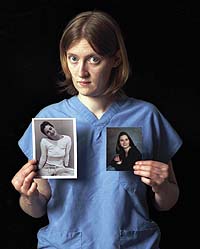

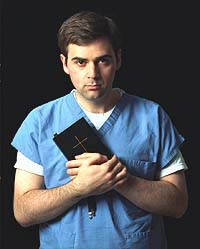

| PERSONAL EFFECTS: (From top) Wasif Ali brought his EMT badge for his portrait; Elspeth Kinnucan, pictures of her two sisters; Arthur Boykin, the Book of Common Prayer; Michelle Mendoza brought Patrick. |

From July 2001 through June 2002, I was on leave from Rochester as a visiting professor in humanism in medicine at New York University’s medical school. I planned to teach medical students about the ways in which photography had been used to portray doctors and patients and how these representations had changed over time. My first “official” day was September 11, 2001.

During that winter, I’d heard about a group of about 20 medical students who had volunteered to assist the staff of the New York City Office of the Chief Medical Examiner.

The office needed volunteers who had some understanding of anatomical nomenclature to transcribe notes taken by forensic pathologists and law enforcement personnel and to help sort, catalog, and identify remains recovered at ground zero.

I became interested in these students and in the unanticipated psychological and emotional consequences of their decisions to volunteer. Some had been in medical school for only a few weeks; all were inexperienced at this work.

The 16 students who agreed to take part were initially wary. Many felt that what they had done was not exceptional and were hesitant to cast themselves in any way as “heroic.” Further, some felt that they had, for one reason or another, let themselves or the victims down and were reluctant to gain attention from what they saw as their failures.

In each case, my argument was the same: The purpose was to document individuals. What students chose to relate about their motivations, experiences, and memories was up to them.

I began photographing and interviewing in a makeshift studio set up in a medical school teaching lab about nine months after the attacks. Students were asked to wear the clothes they wore in the morgues, and to bring something that had helped them deal with the stress, fear, and depression associated with their work.

I asked the students to describe what they did, what they would remember, how they were changed by the experience, and, finally, to describe the significance of their props.

I’ve worked with many portrait subjects. For reasons I still find unclear, these students were surprisingly adept at absenting themselves from the entire process of picture taking. All I really had to do was release the shutter.

More than four years have passed since 9/11. The world continues to experience new tragedies, both natural and manmade. Some have resulted from events described here. Each generates its own stories and images, which are rendered into “history” with the passage of time.

It is hoped that this particular work will preserve at least a small part of a traumatic event and thereby honor the memories of those involved.

Barry Goldstein ’81M (MD), ’82M (PhD), is associate professor of biochemistry and biophysics at Rochester. This essay is drawn from his book Being There (Master Scholars Press/ NYU School of Medicine, 2005). The book is available through the University of Rochester Press. Reprinted with permission.