Rediscovering a Lost Spiritual ‘Book’

Rochester is home to two of the world’sleading authorities on an often

misunderstood religious tradition. By Scott Hauser

|

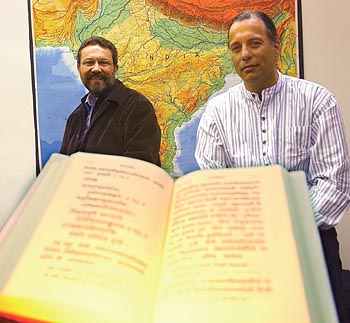

| TANTRA TEAM: Muller-Ortega (left) and Brooks |

Imagine that everything you knew about modern Christianity came from the writings of Thomas Aquinas, the medieval monk who systematically outlined the philosophical and spiritual underpinnings of Roman Catholicism. And let’s assume you’re the curious sort, so you go out and talk to some contemporaries who describe themselves as Christians. But soon you start to wonder: Why don’t their ideas about their faith seem to align with the ancient texts of Aquinas?

And then imagine that, as your curiosity grows, you discover not just a book, but a whole library by Martin Luther, the 16th-century German theologian whose criticisms of what he saw as the church’s excesses sparked the Protestant reformation. And then you discover another vein of thinkers who criticize Luther.

Before long, the picture you have of modern Christianity—and the people who practice it—is quite different.

It’s a simplistic metaphor, to be sure, but according to Douglas Brooks and Paul Muller-Ortega, two top scholars of South Asian religions at the University, it gives a small glimmer of the paradigm shift that has taken place over the last quarter century among those who study Tantra, a commonly misunderstood tradition that dates to the India of about 1,500 years ago.

Thanks to internecine sniping between and among Indian traditions, what began as a reformist religious approach within Hinduism had been neglected—if not actively suppressed—by the keepers of the canon, who often characterized it as little more than a seamy backroom in the mansion of Hindu thought. The little that was known about the tradition in the West came to scholars, for the most part, through its critics.

That is, until people like Brooks and Muller-Ortega began to get curious about how such a profoundly nuanced and influential spiritual outlook could have been painted so one-sidedly.

“Tantra is not just a lost chapter,” says Muller-Ortega, a professor in the Department of Religion and Classics. “It’s more like finding an entire lost ‘book’ of Indian religion. There was a tendency among scholars to skip hundreds and hundreds of years of Indian religious and spiritual life. . . . and then finding thousands and thousands of texts that have been largely ignored in the construction of modern Hinduism.”

Over the past 20 years—Brooks joined the College faculty in 1986; Muller-Ortega in 1997—the two have built international reputations as scholars who are among the leading interpreters of Tantra’s history, traditions, and influence.

Muller-Ortega specializes in the emergence of Tantric thought in northern India through the first millennium of the Common Era. He’s a leading specialist on Kashmir Shaivism, a branch of Tantra that evolved around the Hindu god Shiva and his consort, the goddess Shakti.

Brooks is a pioneering expert in Tantra’s later manifestation in southern India, which centered around Shakti as a goddess in her own right. He traces the tradition as it arose in medieval India, becoming the first American to definitively analyze its influence on the emergence of the goddess tradition known as Shrividya.

“Paul and I are both interested in the 1 percent of Tantra that might be called the philosophically sophisticated and contemplative forms, but at two different stages of its evolution and regional development,” Brooks says. “Our subject was probably the last frontier in Asian religions. For better or for worse, if you want to study in these fields, you have to enter through our work.”

“They are the groundbreaking U.S. scholars in Kashmir Shaivism and its evolution in South India,” says David Gordon White, a professor of South Asian religions at the University of California at Santa Barbara.

As teachers in the Department of Religion and Classics, Brooks and Muller-Ortega have helped introduce a new generation to the study of spiritual ideas as a way for students to better understand themselves and those around them. In courses that often require a passing introduction to Sanskrit and that often rely on student readings of original—and at times paradox-filled—texts, Brooks and Muller-Ortega teach not only on Tantra, but classes on Hinduism, Buddhism, Confucianism, Zen, and other historical, social, and cultural veins of Asian spirituality.

The subjects seem to resonate with College students, who have made the pair’s classes among the most popular at Rochester. In 2002, Brooks received the Goergen Award for Distinguished Achievement and Artistry in Undergraduate Teaching, the College’s annual recognition of outstanding teachers.

Chris Wallis ’01, who is studying for a Ph.D. in religious studies with a focus on medieval Tantric philosophy at U.C. Santa Barbara, says he was interested in Asian religions when he was looking for an undergraduate program. He enrolled at Rochester, he says, to study with Muller-Ortega and Brooks.

“They are engaged in the tradition culturally and spiritually in ways that go way beyond the merely intellectual,” says Wallis, who went on to earn a master’s degree in Sanskrit language and Indian literature at the University of California at Berkeley and another master’s in Indian religion and philosophy at Oxford University. “They are true scholars in that they search for truth honestly and without introducing their own presuppositions, but they do it from within the perspectives of the tradition.”

The tradition of Tantra has fascinated several generations in the West, especially some lay people who seem to be on the lookout for a less-than-rigorous road to spiritual liberation. But, scholars say, from adventurers like Sir Richard Burton in the late 1800s to the host of “tantric sex” manuals on offer in the how-to section of today’s book stores or on the Web, the tradition has been widely misunderstood, misappropriated, and mischaracterized.

From its first appearance in the theological literature of India in middle of the first millennium, Tantra has defied easy classification. Introduced as a new category of “revealed scripture,” the tradition began as a counterpoint to the Hindu Vedas, the traditional scriptural core of mantras and rituals that date as far back as 2,000 B.C.E. and that were believed to provide access to divinity.

Originally meaning “that which extends knowledge,” Tantra offered practitioners an approach based on accessing a divine energy that courses throughout the universe and that’s contained in all experience. Tantrikas—as those who practiced were known—suggested that spiritual liberation was attainable not through the ascetic notion of distancing themselves from the corporeal world but by embracing the world in the proper spiritual context.

Grounded in the guru-adept model in which a qualified teacher initiates students into a set of rituals, deities, meditation, and physical practices, including particular forms of yoga, the tradition involves more than scripture.

As White puts it in a 2000 book, Tantra in Practice, a collection of essays to which both Muller-Ortega and Brooks contributed:

“Tantra is that Asian body of beliefs and practices which, working from the principle that the universe we experience is nothing other than the concrete manifestation of the divine energy of the godhead that creates and maintains that universe, seeks to ritually appropriate and channel that energy, within the human microcosm in creative and emancipatory ways.”

According to Tantric tradition, that energy can be found by those who are willing to commit to looking for it in the right ways, says Brooks. It exists even in desires that most ascetic traditions aim to shun or that Western traditions consider all-too-Earthly temptations, including the desire to have sex or the desire to live a comfortable life.

Liberation is found not by divorcing yourself from the world but, in a spiritual sense, by looking deep into the core of desire, pain, and all the turmoil that comes with existing as a sentient human being. Once properly accessed, the energy that drives that turmoil can be understood and appreciated as part of a more-encompassing divinity inherent in all creation.

Says Brooks: “The great Tantric philosophers invite us to imagine ourselves and our world in ways that we’ve never considered—that the divine is woven into every thought, every desire, every action.”

Such an integrative and holistic understanding seems very modern to most people now, Brooks says. But when it was introduced to a tradition that valued asceticism as the path to spiritual growth, Tantra was a startling revelation.

Religion and Classics

Over the past six years, between 65 and 81 students each year were officially

declared majors in the Department of Religion and Classics, making it one of

the most popular humanities programs in the College of Arts, Sciences, and Engineering.

Another 20 or so regularly declare a minor in the department.

Among the humanities, in which about 19 percent of all students choose to focus

their academic work in the College, only English attracts more students as a

major.

When it comes to clusters—sets of at least three interrelated courses

outside their majors that students in the College must select from the broad

areas of the humanities, social sciences, and physical sciences—many undergraduates

also turn to religion and classics. There are typically more declared clusters

in religion and classics than any other humanities program with the exception

of philosophy and, in some years, music, according to the College Center for

Academic Support.

Founded in the early 1980s, the department is considered a leader in higher

education for its unique combination of the study of the world’s great

religions with the languages of their canons.

Says Muller-Ortega: “This is the opposite of the ascetic tradition. There are spiritual traditions that are negative in their appraisal of the world, and there are traditions that are positive in their appraisal of the world. The Tantric tradition is positive in its appraisal.”

Many scholars, Brooks and Muller-Ortega among them, argue that the main ideas of that worldview found resonance throughout Asia, influencing the history of Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism, and other religions over the past 1,500 years.

As the influence of Tantra spread, tensions arose between some who called themselves Tantrikas and leaders of other traditions, who found it easy to disparage Tantra’s more esoteric rituals as little more than “black magic.”

“Part of its bad reputation is that the Tantrikas are willing to broach subjects that everybody is interested in, but that nobody is willing to ask about,” Brooks says, noting that scholars today recognize that the most highly regarded Indian philosophers of the first 1,000 years of the Common Era were Tantrics.

Both Muller-Ortega and Brooks were first introduced to the tradition as spiritual seekers themselves and both practice a form of the tradition. Brooks encountered Tantra during his junior year at Middlebury College as an exchange student in India, a country to which he has returned many times.

After graduation, he pursued a master’s of divinity degree in language study at Harvard, followed by a Ph.D. in religion.

His advisor suggested he write about Tantra in South Indian goddess cults for his dissertation.

“The real difficulty I had was persuading the Hinduism scholars at Harvard that I wasn’t making it all up,” he says. “Eventually they agreed to let me venture into uncharted territory.”

Muller-Ortega was a student at Yale when he began to study yoga and meditation. He continued with his meditation studies after graduation, completing intense monastic retreats in Switzerland and on the island of Majorca. As a student in the doctoral program at Santa Barbara, his advisor suggested he try to translate the work of Abhinavagupta, a medieval guru and philosopher whose writings were unknown in the West and, more important, had been all but forgotten in India.

Muller-Ortega became fascinated by Abhinavagupta’s teachings about consciousness, the nature of reality, and their connections to the concept of god as denoted by the name Shiva. In traditional Hinduism, Shiva is understood to be part of a male trinity in which he plays the role of cosmic destroyer, reabsorbing creation back into the godhead.

Abhinavagupta has a more nuanced understanding of Shiva as a name for absolute consciousness, one that divinely creates, maintains, absorbs, conceals, and reveals all reality. The nature of Shiva begins with Shakti, his goddess consort. Shakti expresses Shiva’s power, although it is understood that Shakti and Shiva are two aspects of a single reality.

“Tantrics believe that human beings contain levels of reality that you are not ordinarily aware of,” Muller-Ortega says, and through specific practices, these levels of reality can become active.

“The tradition says that you have power, or shakti, within you that can be activated and turned on. This process transforms you. The mind changes, the body changes, the emotions change.”

In medieval times, the Tantric teachings migrated to South India, where Shakti was worshiped independently as a goddess. And the understanding of both consciousness and cosmos as expressed through the goddess and her worship is the scholarly focus of Brooks.

According to Brooks, Tantra aims to access shakti. In contrast to Western religious ideas, in Tantra goodness does not lead to greatness, as in the equation of morality leading to saintliness. Rather, Tantra teaches that becoming powerful—properly cultivating the powers of the body, mind, and heart—creates the potential for goodness and a greatly expanded experience of each indivdual’s humanity.

The ideas at the heart of Tantra have appealed to scholars and seekers for the past 1,500 years, Brooks and Muller-Ortega say, so they’re not surprised that students and lay people of the 21st century find meaning in the tradition.

But as teachers and scholars, they’re most interested in the power of all religious traditions to open doors to the study of humanity.

“The Tantrics begin with a spiritual paradigm,” says Brooks. “I’m not you; I’m not like you; I’m nothing but you.

“Think about that: ‘I’m not you,’ because we’re different people,” he says. “ ‘I’m not like you,’ because we think and feel and understand the world in different ways. But ‘I’m nothing but you,’ because we’re all part of the same creation. How can that be?

“That’s what you try to understand when you study religion.”

Rochester freelance writer Catherine Faurot contributed to this story.