A New Look at Diversity

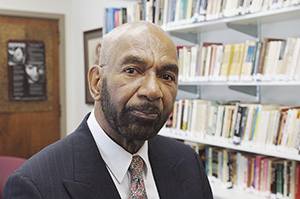

CONVERSATIONS: Jeffrey Tucker, associate professor of English, says University initiatives are sparking new conversations about diversity among faculty. Photo credit: Kurt Brownell.

Helping build a more diverse faculty—in all its dimensions—is the goal of several new initiatives at Rochester. By Kathleen McGarvey

When Jeffrey Tucker joined Rochester’s faculty as an assistant professor of English eight years ago, he was hoping to take part in an important conversation. The specialist in African-American and 20th-century American literature was disappointed.

“I arrived in 1999, and a University-wide conversation about diversity wasn’t happening,” he says.

Tucker thinks he may be hearing such a conversation now as the University takes several new steps to attract, recruit, and retain a diverse faculty, to create a more welcoming environment for women and minority scholars, and to emphasize diversity as an essential part of University life.

“I’d imagine a new faculty member coming to the University in the midst of this conversation being energized and wanting to participate in the conversation and in the work of the surrounding university,” Tucker says.

Like colleges and universities across the country, Rochester is taking a careful look at itself and how well its own makeup reflects that of the world in which its faculty and students live and work. While the demographics of the United States have changed, shifts in faculty populations have been slow to keep up with that trend.

According to current University data, about 2.5 percent of Rochester’s tenured and tenure-track faculty identify themselves as African American or Hispanic, and no faculty members identify themselves as Native American. That percentage of underrepresented minorities is nearly unchanged from 2000.

In February 2006, President Joel Seligman appointed a task force to examine faculty diversity and inclusiveness at Rochester, charging the University-wide committee to suggest specific steps that Rochester could take to improve on both fronts.

After seven months of evaluating data and considering ways to improve its collection, discussing obstacles as well as successful efforts, talking with other universities about policies on their campuses, and developing strategies to make improvements, the Task Force on Faculty Diversity and Inclusiveness proposed 31 recommendations.

LEADERSHIP: Lynne Davidson (left), the University's new diversity officer, will help oversee issues involving faculty diversity. Davidson's appointment, says Nicholas Bigelow (right), chair of the Faculty Senate, puts “someone right in the president's office who is responsible for this issue.”

Seligman adopted each one, including a key provision to create a new position that will oversee faculty diversity efforts throughout the University, a centralized responsibility that is new for Rochester. Lynne Davidson, a deputy to Seligman who chaired the task force, was appointed as the inaugural vice provost for faculty development and diversity.

“The recommendations put someone right at the president’s office who is responsible for this issue,” says task force member Nicholas Bigelow, the Lee A. DuBridge professor of physics and chair of the Faculty Senate. “That action is one that potentially can make the difference.”

Academic leaders say the University is instituting measures—based on the task force’s recommendations—to keep pace with a changing society. The report does not recommend a target goal for faculty diversity; rather it focuses on efforts such as assisting faculty hiring committees to cast a wide net when they seek job applicants and establishing family-friendly policies that will help attract and retain faculty.

In doing so, the University enhances its own competitiveness by drawing top researchers and teachers which, in turn, serve students, faculty say.

Scholars bring perspectives and experiences that shape the questions they ask, the problems they research, and the materials they teach. Simply put, when a faculty is diverse, the field of knowledge broadens—and so do the possibilities students of all backgrounds imagine for themselves.

“We live in a world in which knowledge knows no boundary,” Seligman says. “We educate students for what will be an intensely competitive, multicultural environment, and we want to provide an education that will best prepare our students for this new world.”

FIRST STEPS: Vivian Lewis, associate dean for faculty development at the Medical Center, says the task force's work is an important first step in helping the University become a more inclusive community.

Task force member Vivian Lewis, a professor of obstetrics and gynecology and an associate dean at the School of Medicine and Dentistry who oversees faculty issues involving women and diversity, says the task force’s work was an important first step.

“Most institutions of higher learning . . . don’t perceive themselves as having a problem, or as being unwelcoming,” she says. “That can be an impediment to accomplishing change.”

One immediate change is Davidson’s position as the University faculty diversity officer, a post that will be the “default starting point for faculty seeking help on issues of multiculturalism and its advancement,” according to the report.

While decisions about faculty hiring and other matters will remain with schools and departments, Davidson will help ensure that consistent and comprehensive education and training standards are established and that all searches are inclusive.

She also will work to establish a central clearinghouse to address questions on issues such as local schools, daycare, and resources for children with special needs; provide a central point of contact for deans, department chairs, and faculty who need assistance with job relocation for a spouse or partner; and coordinate annual reporting on the status, progress, and challenges of diversity.

The University faces fierce competition when it comes to hiring talented faculty because top scholars can go anywhere. Added to that is the relatively small numbers of underrepresented minorities and, in some fields the number of women who are in graduate schools studying to be faculty members. In 2004, for example, approximately 16 percent of graduate students were members of underrepresented minority groups, according to the U. S. Department of Education.

Rochester also faces challenges because of its size. Hiring a critical mass of new faculty becomes more difficult when the overall size of the faculty is small.

Rochester, too, is a decentralized university, whose six schools function with significant autonomy.

“Our decentralized structure, which is great for so many things, occasionally acts as a barrier when we need to share ideas and resources, and achieve important economies of scale,” Davidson says.

CULTURE SHIFTS: Ellen Koskoff (above), professor of ethnomusicology at the Eastman School, says examining the institutional culture throughout the University will play a key role in bringing about change. Wendi Heinzelman (below), associate professor of electrical and computer engineering, found a culture in her department that understood her balancing act as a researcher, teacher, and mother of 3-year-old Nate and 1-year-old Molly.

Ellen Koskoff, a professor of ethnomusicology at the Eastman School and a member of the task force, says examining institutional culture is key to bringing about change.

“Every school [at the University] has had, historically, its own way of dealing with these issues,” she says, noting the report recommends that each school analyze its “cultural climate.”

“The value systems that underlie our cultures are where we should be looking, not at the numbers.”

Koskoff’s comments allude to the far-reaching stakes that go into building a diverse faculty.

“If we don’t have a welcoming environment, we’re going to be missing talented people we could have here,” says Bigelow. “We’ll become diverse as we get the best people.”

While recruiting faculty is one part of the equation, retaining faculty is another. The recommendations outline important quality-of-life considerations that are considered crucial to convincing faculty that Rochester is the best place to spend their professional lives.

“When I had my children, my department was extremely understanding,” says Wendi Heinzelman, an associate professor of electrical and computer engineering. “I feel lucky to have been able to spend time with my children and still have a research and teaching career.”

A leader in the emerging field of wireless sensor networks, she balances her role as the mother of a 3-year-old and a 1-year-old with her role as, until this year, the only woman faculty member with a primary appointment in her department.

“One of the reasons I selected Rochester is that I thought it was a very family-friendly place,” Heinzelman says. “People understood you can do good research without being in the lab 24 hours a day, 7 days a week.

“It wasn’t codified anywhere, but I got that sense just in talking to people.”

Thanks to the adoption of the task force recommendations, family considerations will be reflected in University policy. For example, one of the pressures of academic life is that prime childbearing years typically coincide with the time in which faculty members are working to achieve job security through tenure.

One recommendation allows faculty members with new children to pause the progression toward the tenure review that decides their professional future.

Prospective faculty don’t have to try to gauge the environment as Heinzelman did. “It makes people not have to ask,” she says. “It’s there.”

Tucker, father of a baby daughter and now a tenured associate professor, agrees that the family-friendly policy changes are crucial. “These are very important, meaningful moves,” he says.

The task force also called for measures that will help build community and bolster support for all faculty. For women and faculty of color, who may feel alone if they are a minority in their departments, mentoring and other forms of support can be critical.

LIFE LESSONS: Gladys Velarde (above), director of the Strong Women's Heart Program, says faculty diversity is an important component in the University's obligations to serve students and to treat patients. For Jesse Moore (below), professor emeritus of history, mentors provided important lessons: “They made me feel a part of the University.”

Jesse Moore—a professor emeritus of history and a scholar of 20th-century American, African-American, and South African history—came to the University in 1970. For some years, he was the only African-American, full-time faculty member on the River Campus.

He attests to the power of mentorship. “I was fortunate to be in a department and at a university with people—Professors Eugene D. Genovese, Stanley Engerman, Robert Hall, and Presidents W. Allen Wallis and Robert Sproull—who were senior and took an interest in me,” he says. “They made me feel a part of the University.”

With greater faculty diversity, a diverse student body benefits.

“If there’s nobody around who looks like you, you feel isolated—and that’s no way to do your best,” Bigelow says.

Gladys Velarde, the first woman faculty member in the cardiology division at the Medical Center and the director of the Strong Women’s Heart Program, says achieving faculty diversity is essential if the University is to meet its obligations in serving students on its campuses and patients in its medical facilities.

“The population is changing,” she says, “and the faculty is not. Because of that disparity, we have to rise to the challenge. Our goal is a better community.”

The University has set itself on a road toward that community, and Davidson sees unity of purpose.

“Everyone I’ve talked to really wants this to succeed,” she says. “Making this a welcoming University is beneficial to everyone, and we’re all in agreement on that.”

When Velarde looks ahead, she knows what she hopes to see at the University: “An environment where we’re diverse but united, and we don’t have to convince anybody this is a good thing, because that will be intuitively obvious.”

Kathleen McGarvey is a writer in the Office of Communications.

Recommending Change

President Joel Seligman called the recommendations from the Task Force for Faculty Diversity and Inclusiveness “the basis for further significant progress in making our University a more inclusive and welcoming campus for all faculty regardless of gender, race, and ethnicity.”

The recommendations focus on four broad areas:

University-wide coordination of efforts to make Rochester a more diverse and inclusive institution

Funding to take advantage of special opportunities in hiring

Family-friendly policies

Best practices across the board for the successful recruitment and retention of all faculty.

To read the full report, visit www.rochester.edu/diversity.

The recommendations were made unanimously by a group whose members included the provost, the senior vice president for health sciences, the senior academic dean of each of the six schools, the chair of the Faculty Senate, and faculty from throughout the University.

“These were people with all different kinds of perspectives, from different schools and departments, men and women, deans and faculty at all levels, members of different groups—and we all agreed on these 31 recommendations,” says Lynne Davidson, chair of the task force and deputy to the president.

Seligman has appointed Davidson as the University’s first vice provost for faculty development and diversity.

—Kathleen McGarvey

National Comparison

The median percentage of women on the faculty among a group of private, selective colleges and universities that includes Rochester is about 29 percent, according to figures provided by the Consortium on Financing Higher Education (COFHE).

The median percentage for underrepresented minority faculty members is about 6.1 percent.

The consortium figures are based on the fiscal year that ended June 30, 2005, the most recent year for which data for all the institutions are available. For comparison purposes, the COFHE figures also do not include medical faculty because not all the universities have medical schools.

COFHE is a 31-member academic organization that was created in the 1970s to foster discussion on higher education issues among a small set of peer institutions.

—Kathleen McGarvey