Putting the Notes Together

Broadway legend Charles Strouse ’47E reflects on his composing career.

By Katina Antoniades

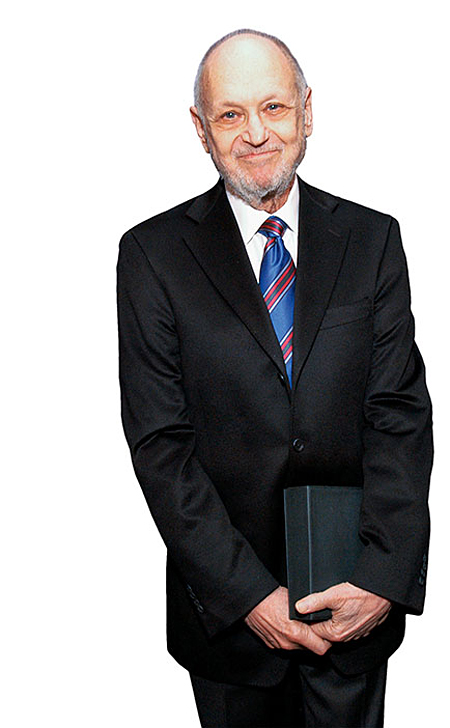

COMPOSED: Strouse is celebrating his 80th birthday with the publication of a new memoir, Put on a Happy Face, and by preparing a new musical, Minsky’s, scheduled to open in January.

Composer Charles Strouse ’47E is in the midst of being feted with a series of events to celebrate his 80th birthday. Despite his laundry list of honors and a remarkable career that has produced megahits like Annie and Bye Bye Birdie, Strouse shows no signs of slowing down. He has published a memoir, Put on a Happy Face; his new musical, Minsky’s, opens in Los Angeles in January; and he’s working on adaptations of Paddy Chayefsky’s film, Marty, and Theodore Dreiser’s An American Tragedy. This fall, he returns to the Eastman School as a special guest for Eastman Weekend, which is held in conjunction with Meliora Weekend, Oct. 16–19.

In an excerpted interview, Strouse talks about Eastman, composing, and his dreams of success.

Excerpt

‘I Can Do That!’

A budding composer realizes who’s really listening.

By Charles Strouse ’47E

As a composition major, I worked diligently at honing my sense of pitch (via endless exercises of copying down notes and harmonies played by someone else), as well as four-part writing in the style of Bach. We did endless analyses of the Beethoven Quartets, and of the piano music of Mendelssohn and Brahms. It was incredibly challenging. Learning had come easy to me when I was younger, but this was something completely new, and I was feeling my way in the dark, not knowing what was at the end of the tunnel. I couldn’t even see the light.

I dutifully spent my days buried in musical theory and practice, but patriotism (plus the fact that I lost the expensive fountain pen my brother and sister gave me as a going-to-college gift and wanted to replace it) prompted me to take a job at a war plant helping to make shells for navy rockets. Each shell weighed fifty-seven pounds, and was very hot. I had to lift each one from a passing rack (wearing thick gloves and protective shoes in case I dropped one), then measure the shell’s width with a caliper, and weigh it. I did this each evening from 6 p.m. until midnight. Then, the next morning, it was back to Bach and Palestrina.

Besides being exhausted, I was homesick.

In an act of desperation, one night I phoned home collect and begged my father to let me end the pain by leaving school and coming home. He was having none of it.

ART’S PLACE: Strouse, who was 15 when he enrolled at the Eastman School, says the experience “swerved my life . . . from somebody who merely had aptitude into somebody who developed a love of the art.”

“A man’s got to finish what he starts,” he proclaimed.

So I persevered. Lacking the imagination yet to have, or even seek, my own voice, I would go to classes and to concerts, not knowing if I liked or didn’t like the music. I just listened, absorbed, and later tried to write music in similar styles.

In 1945, the first George Gershwin Memorial Award (Gershwin had died in 1937) for a new symphonic work was presented to Peter Mennin ’45E, ’48E (PhD), a graduate student at Eastman, who later went on to become the president of Juilliard. As I listened to the workmanlike and energetic piece, I thought (as lyricist Edward Kleban in A Chorus Line put it), “I can do that!” Suddenly, I knew that I could be 1946’s George Gershwin Memorial Award winner. This could be the answer to all my problems. Everyone would notice: friends, family, teachers . . . the whole world!

The piece I wrote was called Narrative for Orchestra, a cunning title, I thought. The orchestration was sonorous, and the composing itself was sober, yet not without charm—filled with humor and craftily put together. I became more and more convinced that this was my time. I would have my moment in the sun.

After waiting for what seemed an eternity, the letter from the judging committee finally arrived. It read, “Thank you for your submission. This year, out of the many submissions we received, we didn’t find any worthy of the prize.”

I reddened as I read it.

I’d studied and worked so hard. But no one cared. No one, that is, except my friend Bill Flanagan, to whose dorm room I ran for solace. Bill was just reassuring me that I was a really good composer when my insecure side piped up. “What does it matter if I’m a good composer, anyway?” I asked. “Nobody’s listening.”

“Does it matter?” Bill replied, as he took another puff on his cigarette.

For me, it was as if a light bulb had just been turned on. What was that slogan MGM used after the lion roars at the beginning of every movie?

Ars gratia artis. “Art for art’s sake.”

That same year, in 1946, I wrote a short opera that was never performed and never shown to anyone. In it, two musicians—a violinist and a cellist—in a trio that plays dinner music in a restaurant are waiting in the kitchen for the third player, the pianist, to arrive.

When the tardy player finally gets there, he is sloppily dressed and full of attitude. The violinist, the eldest of the group, tells him his demeanor must improve.

The young pianist says, “Who cares? We’re just background music for eating. Nobody’s listening.”

The cellist says, “We’re listening. That’s somebody listening.”

I was beginning to learn what that MGM slogan really meant.

© 2008 by Charles Strouse. The essay is excerpted from Strouse’s book Put on a Happy Face (Union Square). Used with permission. All rights reserved.

I imagine you have a very busy schedule. What made you make time for Eastman Weekend this fall?

Well, I have a certain loyalty, you know, because that was a very important few years of my life. It’s formative for any musician, but particularly so for me because it swerved my life around, from somebody who merely had aptitude into somebody who developed a love of the art.

How does your career compare to what you hoped for after graduating from Eastman?

Well, I don’t know. I hoped for adulation and success, and I hoped to be a good composer. I hope I’m a good composer; I still feel as though I’m trying all the time. When I can’t sleep, sometimes I wonder, “What am I hoping for?” I don’t know what most musicians hope for; one side of it is to simply be technically proficient, but I think we all want more than that. I think we want to express a side, or an inside of ourselves. I’m still trying to answer that one, and in my opinion, a lot of composers are.

Are there certain songs you’ve written that were more or less popular than you expected?

If you’re talking about musical comedy songs, yes. There was a song in Annie that we put in very late in the show, because the beginning of the show wasn’t working. We had started out with girls singing “Hard Knock Life” and then we started out with a lot of guys on the street selling apples, and the audience was restless. We put in a song called “Maybe,” which was a very, very simple song, but the sentiment at exactly that moment from that orphan girl quieted the audience.

In what ways have you seen Broadway change since the ’60s?

One of the great changes is that the critics are very conscious of the style of music, that you can get hung very quickly for being “old fashioned.” The reverse of that, you can be very easily praised for writing what’s called rock ‘n’ roll. The critics want to be “with it.” It would seem that it’s supposed to be the other way around, that we’re supposed to be with them if we want to be—but they really want to be “with it.”

What do you regard as your favorite success?

Actually, two of my favorite shows were not successful. One was Rags. And Golden Boy was successful but it never went down as one of the classics—and it was a flawed piece in many ways. And I loved Annie. I don’t even know why a certain note really follows another note. I sometimes think it’s a dream. And if I get very lucky, it turns out to be a nice dream.