Features

MEDIA MAN: A newly restored print of the 1922 movie Robin Hood, starring Douglas Fairbanks and Enid Bennett (page 35 and opposite), will have its debut during the Robin Hood conference, thanks to the work of the George Eastman House. The conference will explore the many ways that the Robin Hood story has been portrayed in literature, film, and popular culture and will feature an exhibition of memorabilia. (Photo: George Eastman House Motion Picture Department Collections)

MEDIA MAN: A newly restored print of the 1922 movie Robin Hood, starring Douglas Fairbanks and Enid Bennett (page 35 and opposite), will have its debut during the Robin Hood conference, thanks to the work of the George Eastman House. The conference will explore the many ways that the Robin Hood story has been portrayed in literature, film, and popular culture and will feature an exhibition of memorabilia. (Photo: George Eastman House Motion Picture Department Collections)Lythe and listin, gentilmen,

That be of frebore blode;

I shall you tel of a gode yeman,

His name was Robyn Hode.

—A Gest of Robyn Hode

First mentioned in medieval ballads, Robin Hood has been an iconic figure in English—and now world—culture for more than seven hundred years.

A wily outlaw, a force for good in a corrupt society, and in many—though not all—versions, a displaced nobleman who robs the rich to give to the poor: This is the Robin Hood that has come down to us through the centuries, and who remains a vivid part of popular culture today, as a new movie now in the works—with Russell Crowe this time inhabiting the part of the folk hero—attests. He’s already been portrayed by actors from Errol Flynn to Daffy Duck.

“Robin Hood is a fixture in our mental baggage,” so ubiquitous that “most people can’t identify when they first heard of him,” says Thomas Hahn, a professor of English, a specialist in medieval literature, and a lifelong devotee of the Robin Hood legend.

In October, Hahn and other scholars of the Robin Hood story will put that baggage under scrutiny at the seventh biennial conference of the International Association for Robin Hood Studies. The conference, which will be held at the University—its inaugural site—this year takes on the theme “Robin Hood: Media Creature,” and participants will examine the many genres and forms that have taken up the figure of Robin Hood, from plays and poems, to films and comic books, to novels and toys. The Eastman School and the George Eastman House International Museum of Photography and Film will contribute to the program, too.

Whatever the form, Robin Hood’s appeal is a constant.

“It’s important that the story is itself so slender—just a guy, a forest, a bow and arrow, and some resistance actions: a story that can be radically varied to relate to changing circumstances without seeming to distort the myth,” says Stephen Knight, a distinguished research professor in English literature at Cardiff University in Wales. “Most of the other great myths—Oedipus, Beowulf, Arthur for example—have detailed, even fixed, stories and are hard to adapt without seeming to destroy the myth.”

“It’s strange because there is no classic original story, as with, say, the story of Troy. Yet there seems to be a deeply attractive core element,” says Helen Phillips, also a professor of English at Cardiff University and a plenary speaker at the October conference. “Perhaps what we like is a paradox, someone who defies authority yet is a good outlaw.”

“People usually first ask, ‘Was he real?’,” Hahn says. “It’s a desire to ground our affection for Robin Hood in the fact that he was a real person.”

Scholars have pointed to people named Robin, or Robert, Hood in historical records, but there is no single figure who seems to have inspired the Robin Hood stories.

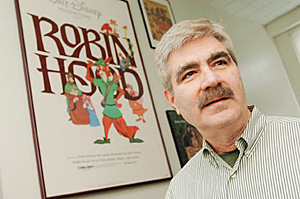

PROFESSOR & DEVOTEE: Thomas Hahn, a professor of English at the University who helped organize the original conference as well as this fall’s edition, is also a devotee of the Robin Hood legend with more than 2,000 items in a personal collection. (Photo: Richard Baker)

PROFESSOR & DEVOTEE: Thomas Hahn, a professor of English at the University who helped organize the original conference as well as this fall’s edition, is also a devotee of the Robin Hood legend with more than 2,000 items in a personal collection. (Photo: Richard Baker)A Robin Hood Review: Picks and Pans

With the sheer variety of Robin Hood incarnations, those who study the outlaw hero are bound to have some favorites—and to wince at a few clunkers.

“I’ve spent a good deal of time in the last year burrowing through the treasures in the George Eastman House photographic archives,” says Thomas Hahn, a professor of English, “and the spectacularly athletic Robin Hood invented by Douglas Fairbanks (1922) has become one of my favorites: His capacity to ‘fly’ (using film magic) renders him a kind of ‘Air Fairbanks,’ defying gravity as the avatar of Michael Jordan. And like Mike, ‘Doug’ became a universally recognizable icon of America as a source of limitless energy and action, a place whose media heroes made you feel that anything is possible.

“My least favorite Robin Hood is probably the one-dimensional figure drafted by moralists (in children’s books) or polemicists (as in the rash of ‘Robin Hood Obamas’ that reduce politics to bumper-sticker cliches) to choke off the openness that overflows so many stories about this shape-shifting outlaw.”

For Helen Phillips, a professor of English at Cardiff University and editor of Robin Hood: Medieval and Post Medieval and Bandit Territories: British Outlaws and Their Traditions, the range of options is part of the fun. Her favorites? It’s hard to choose, she says. “Errol Flynn and the Muppets. That’s two choices. But the combination sounds even better.”

Don’t try to win her over by screening Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves (1991), however. “My least favorite Robin Hood is the Kevin Costner one,” she says.

Russell Peck, the John Hall Deane Professor of English, is interested not only in Robin Hood but also in the Arthurian legends. “There’s only one film I know of that combines the two,” he says. “It’s The Siege of the Saxons from 1963.” In it, a Robin Hood-style outlaw intercedes in an effort to overthrow the king, and eventually marries the king’s daughter.

“My favorite is Robin Hood and Guy of Gisborne”—a medieval text that is “so weird, and an incredible buddy adventure,” says Valerie Johnson, a doctoral student in English. Another sentimental favorite for her is The Outlaws of Sherwood, a 1989 fantasy book that first drew her to Robin Hood lore.

The recent BBC series Robin Hood earns Johnson’s vote for the least satisfying depiction.

“I hate a self-centered Robin Hood,” she says. “And that Robin Hood seems a little too immature, too boyish. It strikes me as not quite fitting into the established story.”

“I think the 1938 Errol Flynn film is the all-round star for technique and theme, bringing the ultimate in Hollywood skills to bear on a world-relevant theme of liberty,” says Stephen Knight, author of Robin Hood: A Mythic Biography.

“I also speak up for Mel Brooks’s Robin Hood: Men in Tights as both comical, including silly, and also as a quite searching parody and therefore critique of much of the Robin Hood tradition, especially but not only in film,” Knight adds. “My students get a lot out of it, not only laughs.”

—Kathleen McGarvey

“Historians have been too successful, in that they’ve produced too many candidates” for being the original Robin Hood, “none more compelling than the other,” says Hahn.

But while there may be no evidence of a single real man behind the heroic story of Robin Hood, there were plenty of outlaws in 14th-century England who could have provided the inspiration, says Richard Kaeuper, a professor of history at Rochester. A medievalist, he has written books on justice and public order and on chivalry.

“A lot of medieval outlaw stories turn on justice proclaimed—and not provided,” he says.

“Robin Hood legends are subversive,” says Russell Peck, the John Hall Deane Professor of English. “They always involve him subverting those with authority and wealth—sheriffs, mayors, churchmen, dukes.

“His honor lies in his belief in a moral structure common to the culture, but abused by those in power.”

The story “always becomes more prominent in times of stress,” he adds, and finds its own relevance today. “I suppose the Robin Hoods in our day become those people who dare to oppose large corporations or big government to expose wrongs and gain a fair hearing.”

But the Robin Hood story is not as radical as it might appear, cautions Knight. “Robin represents natural justice, a figure of interest to all who feel authority has not treated them too well: He has a safety-valve function rather than a revolutionary one.”

The roots of the Robin Hood craze are anonymous ballads, other poems, and plays from medieval England. “They’re the origins of the whole story, which makes them interesting. And there are elements—the fights, robbery, resistance to authority, friendship with Little John—that remain,” says Alan Lupack, an adjunct professor of English and curator of the Rossell Hope Robbins Library, a special medieval collection in Rush Rhees Library. Lupack oversees the Robin Hood Project, an online collection of texts, images, bibliographies, and basic information about Robin Hood and other outlaw tales (www.lib.rochester.edu/camelot/rh/rhhome.htm). Lupack created the project in conjunction with the first Robin Hood Studies conference in 1997.

“They’re often very violent stories,” Kaueper says of medieval Robin Hood texts. “It was a very violent society.”

Yet there’s also something fundamentally lighthearted in the lore. “People enjoy outlaw stories. We like to see authority challenged, put down, or made right,” he adds.

In the earliest tales, Robin Hood is having fun—he’s not powerful or a nobleman, says Hahn. But the story took on a new twist in the Renaissance, when Shakespeare contemporary Anthony Munday wrote two plays—The Downfall of Robert, Earle of Huntington and The Death of Robert, Earle of Huntington—that recast Robin Hood as an aristocrat. It was a revision that stuck.

“The Robin Hood story is, to some degree, almost infinitely expandable,” Hahn says. So the 19th and 20th centuries brought further gentrification and refinement of the once rough outlaw, and the romance element of the story blossomed with the introduction of Maid Marian. Absent in the early ballads, Marian became an indispensable part of the tale when the movies took up Robin Hood, Hahn says.

“The landowning, woman-friendly Robin is different from the male outlaw of the early ballad,” Knight says. “He actually, by being set in the time of bad King John, supports true royalty, where the early guy is pretty skeptical about royalty and authority—state and church—in general. So the myth has become more inclusive—or as I would say, more conservative.”

Phillips sees a less conservative trend in Robin Hood’s evolution. As the figure has developed, “one clear change is the much greater morality of the modern Robin and his men. Today he’s always fighting clear injustice or a usurping ruler. That’s shown in the way newspapers frequently label as a Robin Hood someone who helps ‘the poor’ by, in some way, ‘robbing the rich.’”

“By 1922, I would argue, American popular culture ‘owns’ the Robin Hood legend—but not in terms of changing the content,” Hahn says. Errol Flynn and Douglas Fairbanks made Robin Hood a creature of Hollywood, but he nevertheless remains rooted firmly in the medieval English countryside.

It’s a key dimension of his appeal, Hahn suggests.

“I think Robin Hood has operated as an escape to some extent,” he says. When cheaply and widely spread stories about Robin Hood began to be published in the 19th century, the sylvan England the hero occupies was already a memory.

“It became escapist literature for city dwellers. It was already a preindustrial myth for industrial era readers. The greenwood”—the forest inhabited by Robin Hood and his merry men—“is a utopian space.”

One of the classic versions of the story is Howard Pyle’s 1883 book, The Merry Adventures of Robin Hood. Produced in a handsome arts and crafts edition—and expensive for its time at $4.50—the book helped Robin Hood make the leap to children’s literature, just emerging in the 19th century. As Hahn points out, Pyle’s Adventures was sandwiched by the publication of two other classics of children’s literature: Mark Twain’s Tom Sawyer in 1876 and Huckleberry Finn in 1884.

A children’s book was the way into a lifelong fascination for English doctoral student Valerie Johnson, who has organized the conference with Hahn. At age 10 she read the book The Outlaws of Sherwood.

“I was absolutely enthralled,” Johnson remembers. Her interest ultimately took a scholarly form, when she wrote an undergraduate thesis on Robin Hood at Smith College and then a master’s thesis at Rochester under Hahn’s direction. Today she is beginning work on her dissertation in medieval literature. It won’t be about Robin Hood, but she’s sure he’ll work his way in, she says.

“Robin Hood is such an expansive topic,” she says. “You can be working in almost any period.”

Indeed, that’s one of the premises of this fall’s conference. The conference will bring together literary critics, historians, folklorists, anthropologists, musicologists, and experts in film, children’s literature, graphic novels, and comic books.

In addition to academic panels, the conference will feature a range of performances. Among the events are the screening of the earliest surviving Robin Hood film, a newly restored nitrate print of the 1912 version of Robin Hood, filmed in Fort Lee, N.J., then the center of movie-making in the United States; a concert of early lute music; a performance of Robin Hood operettas by Steven Daigle, an associate professor of opera and dramatic director of Eastman Opera Theatre, and singers and musicians from the Eastman School and the College; and the world premiere of a tinted nitrate print of Douglas Fairbanks’s 1922 Robin Hood, newly restored by Rochester’s George Eastman House and the Museum of Modern Art.

“This is the best-known silver screen version of Robin Hood. It was one of the films that gave Douglas Fairbanks his reputation as a swashbuckling hero,” says Ed Stratmann, associate curator of motion pictures at the George Eastman House.

Gillian Anderson, a conductor specializing in silent-film scores, will conduct an orchestra in the newly reconstructed original score.

“It’s marrying traditional academic resources with the performing arts,” Hahn says. “When you focus on the academic only, you miss any sense of Robin Hood’s capacity to ‘catch’ you.”

He knows that capacity well. Hahn collects Robin Hood items—it’s one of the most extensive such collections in the world, he notes, with more than 2,000 pieces, including books, movie posters, musical scores, theater programs, and advertisements.

The “real” Robin Hood may never have existed, but Hahn’s collection, and the gathering of scholars intrigued by the tale, both give evidence to a different—and very contemporary—kind of vitality.

“Robin Hood has always been a creature of the media,” says Hahn.