Features

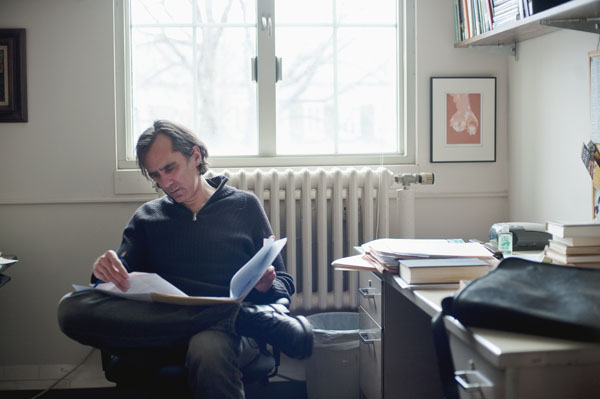

Poetic progress: “To write one poem, you have to read a thousand of them,” says poet James Longenbach, the Joseph H. Gilmore

Professor of English. (Photo: Adam Fenster)

Poetic progress: “To write one poem, you have to read a thousand of them,” says poet James Longenbach, the Joseph H. Gilmore

Professor of English. (Photo: Adam Fenster)A cell phone trills. A BlackBerry vibrates, bristling for immediate attention. “Tweets” accrete, each bearing fleeting news of someone’s latest passing thought on Twitter. Now, now, now, now, now.

In an era of such frenzied exchange of language, it might seem that there would be little place for the poem. But poetry never has been more alive at Rochester than it is today, in writing workshops and poetry readings, informal gatherings and solitary sessions where a writer confronts a blank sheet—or screen. Far from being blotted out by contemporary mores of communication, poetry provides a kind of corrective.

“Poetry, like all great writing, whether poetry or prose, forces you to be very slow,” says James Longenbach, the Joseph H. Gilmore Professor of English and an acclaimed poet and literary critic. “You have to read very slowly. You have to write very slowly. That’s what I say to people who say they don’t understand poetry.

If you try to speed through language the way we do in most of our lives, poetry will be not just irrelevant, but incredibly frustrating.”

Speed, succinctness, transparent and uncomplicated meaning—these are the currency of now ubiquitous electronic communications. But poetry, which also concerns itself with condensation of thought, is an art of shades of meaning, ambiguities of purpose, and the pleasures of language itself.

“We’ve become the culture of the sound bite—and poetry is precisely the opposite of that,” says Thomas DiPiero, a professor of French and of visual and cultural studies, as well as the senior associate dean of the humanities. “It’s a way of thinking—a very specific way of thinking. It’s been called ‘concentrated thought.’ ”

And, judging by the English majors as well as students from disciplines throughout the College who fill English literature classrooms each semester, it has a powerful appeal.

“There’s a strong sense, a thrilling sense, of writing among the undergraduates, and not just of poetry but of fiction as well; you can’t have one genre without the other,” says Longenbach, the author of critical works such as The Resistance to Poetry and The Art of the Poetic Line, as well as volumes of poetry including Draft of a Letter and Fleet River.

Well-versed: Poet Jennifer Grotz, an assistant professor of English, will edit a poetry series for Open Letter,

the University’s literary translation press. She also teaches in the translation program.(Photo: Adam Fenster)

Well-versed: Poet Jennifer Grotz, an assistant professor of English, will edit a poetry series for Open Letter,

the University’s literary translation press. She also teaches in the translation program.(Photo: Adam Fenster)Offered through the English Department, the poetry workshops that Longenbach and colleague Jennifer Grotz, an assistant professor of English, teach are part of the department’s creative writing program. Directed by Joanna Scott, a novelist and the Roswell S. Burrows Professor of English, the program is grounded in an understanding that writing is a creative discipline that draws on the study of a wide range of literature.

“In workshops, half our time is spent reading the greatest poems we can read,” says Longenbach, whose poetry has also appeared in publications such as The New Yorker, The New Republic, Slate, and The Paris Review. “To write one poem, you have to have read a thousand of them.”

Grotz, whose poetry volume titled Cusp won the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference Bakeless Prize in 2003, says that she teaches students to “read as a writer would.” Joining the University faculty last fall, Grotz also translates French and Polish poetry and will teach in Rochester’s new literary translation program.

Grotz found her own way to poetry slowly, teaching herself by reading other poets before taking up the academic study of poetry. A Texan who grew up “in a house with no books,” she was “like a musician who could pick out a tune,” she says.

In her students, Grotz seeks to develop a facility with writers’ tools. “My philosophy of teaching at least introductory-level poetry is to break it down into what writers call ‘craft lenses.’ To have the students think of themselves as writers, with skills they want to develop—image, music, and so on.”

For Giulia Perucchio ’13, who took Grotz’s workshop last fall, that approach was invaluable. “We connect huge, fluid things with very specific images,” she says. A graduate of Rochester’s School of the Arts, she came to the University already focused on creative writing. “That’s the best thing I learned from her: how to be very specific, very direct.”

Poetry’s roots at Rochester run to the University’s beginning. Ashael Kendrick, a scholar of Greek and one of the professors who came to Rochester when the University was first formed in 1850, translated and anthologized poetry. In 1968, Anthony Hecht ’87 (Honorary), the former John H. Deane Professor of Rhetoric and Poetry, received the Pulitzer Prize for poetry while at Rochester, where he was a member of the English department for 18 years.

In many ways, the name most closely associated with verse at Rochester is that of the late Hyam Plutzik, who preceded Hecht as the John H. Deane Professor of Rhetoric and Poetry and taught at the University from the mid-1940s until his death in 1962. A widely published poet concerned with themes such as the relationship between science and poetry, Plutzik taught writing workshops and gave weekly poetry readings on campus.

Today he’s memorialized in the Plutzik Library for Contemporary Writing at Rush Rhees Library, where professor emeritus and poet Jarold Ramsey is also honored with the Jarold Ramsey Study. The library houses the William and Hannelore Heyen Collection, an extensive poetry archive assembled by poet Heyen. Rare Books, Special Collections, and Preservation also holds collections—including early editions, manuscripts, and correspondence—by John Dryden, Hilda Doolittle (H.D.), John Gardner, Carl Sandburg, and Alfred, Lord Tennyson, and other notable poets.

Tyler Goldman ’10, an English major with a creative writing emphasis from Balacynwyd, Pa., took part in the literary translation program’s inaugural course, translating Roman lyric poetry into English. He says among the values of literary translation is its ability to heighten a writer’s awareness of language. “It allows you to think critically about the way language operates,” he says.

That awareness is key to any writer’s development, Longenbach says. “I teach poetry almost exclusively as craft,” he says, “how we focus and sharpen the way we harness language. I tell students we’re almost never going to talk about the subject of a poem. What’s unique is the way the language takes you through the experience.”

There aren’t a lot of different subjects for pop songs, he observes, but we listen to our favorites again and again. Why? It’s not that we can’t recall them—quite the opposite. It’s our attraction to how they express an experience. Poetry, which he calls a “sonic art,” is the same.

“You read a poem many times, not because you can’t remember the words, but because you want to inhabit the way it moves through language.”

Pulitzer Prize–winning poet Galway Kinnell ’49 (MA) agrees. A poem is “not just an exposition of an idea or an event, but a reliving of it,” he says. That evocative force lies in the images and music its words create.

“In poetry workshops, I find, students learn to attend to the precision of their language more powerfully than in any other class I teach,” says Longenbach, who became interested in poetry in college, after having spent “a great deal of my youth involved in music, as a pianist.”

Such exactness is not what everyone anticipates, however. Grotz and Longenbach find ways to help their students appreciate that poetry—like all art forms—requires a blending of feeling and craft.

“You’re working with young people who feel passionately about something, and you’re helping them learn how to connect that passion to a passion for the beauty and accuracy of language,” says Longenbach.

Strong emotion can be an impetus for a poem, but it’s not enough. “People who write not-very-good poems have compelling emotions, too,” he says, “but they haven’t figured out how to get it on the page.”

In Grotz’s workshop, Rainer Maria Rilke’s Letters to a Young Poet, a slim volume of correspondence from Rilke to an aspiring poet, helps frame discussion of the emotive dimension of poetry. She delivers the book to students in a sealed envelope, just as a letter would arrive.

“To my mind, Rilke really helps to address the other reason young poets turn to poetry: expressing themselves, thinking about what it means to be human,” says Grotz. “I contain our ‘soul talk’ to Rilke. Otherwise we focus on technique. It helps us talk more clinically about the craft—but it’s very hard to talk about one without the other.”

“Technique is what allows empathy to come through as empathy and not just as ‘I have these emotions,’ ” says Emily Claman ’06. After graduating with a degree in philosophy, she earned an MFA with a concentration in poetry from Washington University in St. Louis and credits her work with Longenbach and poet and former Rochester faculty member Sally Keith for her pursuit of a poetic career.

When he was an undergraduate, poet Ilya Kaminsky recalls, Longenbach spoke with him “on a line-by-line basis” about poets Frost, Lowell, Walcott, and Ashbery.

“Just think of it: James Longenbach, famous poet and literary scholar, has spent hours and hours of his time reading poems of a first-semester freshman who did not even know English well at that time,” says the Odessa, Ukraine, native who is now a professor of poetry at San Diego State University. “Such generosity of spirit is what makes education possible and what truly propels talent to grow.”

Workshops are not the only courses in which Rochester students encounter poetry, of course. And poetry doesn’t stand alone, says Longenbach—“There’s a climate of writing here: fiction, poetry, and increasingly, playwriting”—nor is it separate from the work of the larger English department.

When Kenneth Gross, a professor of English who has published extensively on Renaissance and modern verse, teaches his course on lyric poetry, he guides students in “slowing down, and dwelling on images and ambiguities.”

Such ambiguities are an irreducible part of poetry’s complexity, and its power—a dimension, in fact, of the very precision Grotz and Longenbach instill. “Poetry works, and sticks around, because it’s not clear. There’s something that can’t be put into words, even though it is words,” Gross says.

Poetry “makes you consider multiplicities—often contradictory multiplicities—of meaning,” says DiPiero. “Reading poetry is like reading the world.”

And while students in his courses—not just English majors, but an “impressive range,” says Gross—might be uncertain in approaching poetry, he reminds them that “they have a lot of experience with rhythmically shaped language: nursery rhymes, prayers, music lyrics, epitaphs, even jingles.”

In his lyric poetry course, Gross—author of books such as Spenserian Poetics: Idolatry, Iconoclasm and Magic and Shylock is Shakespeare—focuses on Shakespeare’s sonnets and the poems of John Keats, Emily Dickinson, and Elizabeth Bishop. They’re short works that “give them a sense of a single poetic intelligence,” he says. “For these poets, the major poems are the intense, short lyrics. They’re very meaty objects of analysis.”

But he shows students, too, that poetic language inhabits places they might not expect. In one course, he spent a week examining with students the texts of national anthems such as the Star Spangled Banner and La Marseillaise.

“It made them take up things they didn’t think of as poems—or even as things to be read—and see them as rather charged.”

Not to be overlooked, either, is the sheer enjoyment that engaging with a poem as a writer or a reader can provide. “However dark or difficult a poem, in some way it has to foreground pleasure,” says Gross.

That pleasure is what feeds literary readings like the Plutzik Reading Series, which brings readings by contemporary novelists and poets to the Rochester community.

“The Plutzik Series pulls an audience beyond the classroom—and also feeds back into the classroom,” Gross says, as faculty members—particularly Longenbach, Scott, and now Grotz—incorporate work by visiting writers into their courses.

Like the Neilly Series, a writers’ lecture series supported by an endowment from Andrew H. ’47 and Janet Dayton Neilly, the Plutzik Series is “a huge part of the literary community here. It transcends poetry,” says Goldman.

“Often, when I taught poetry classes, even workshops,” before coming to Rochester, “there was a part of my job that was being a salesman” for poetry, Grotz says. “Here I don’t feel the need to sell poetry at all. The students come interested and hungry.” How to keep them fed, she adds, “is a wonderful problem to have.”

For Samantha Miller ’11, a double major in English and philosophy from Henrietta, N.Y., who is in Grotz’s workshop this semester, poetry counterbalances the more impatient and utilitarian interaction with language she has in other facets of her life. “We’re so used to text messaging, e-mails—instant gratification and immediate answers. And poetry takes a lot more time,” she says. “In a sense, poetry doesn’t fit with our times, but I think that makes it even more important and valuable.”

Miller hopes one day to teach poetry at the college level and says her literary study at Rochester has shaped not only her professional ambitions but also the very way she sees the world.

“What you can gain by studying poetry is a new set of eyes,” says Miller. “You have a new appreciation for even the most minute things around you.”

It engenders, says Kinnell, “a tenderness towards existence.”

Ultimately, Grotz suggests, there’s even something elemental to it.

“Everybody knows poetry isn’t what you do to make money,” she says. “And it’s not read the way popular fiction is, by any means. It may seem like an old-fashioned thing to do. But it’s the perfectly packaged thing for a human being. It’s totally human-shaped, human-made.

“It’s breath.”