Alumni Gazette

(Illustration: David Cowles for Rochester Review)

(Illustration: David Cowles for Rochester Review)Dave Moreau ’98S (MBA) says he’s “not really a computer guy.” But he says if you’ve got an idea, “don’t let the technology stop you, because there are experts who are good at it who can walk you through it.”

An engineer at the Marietta Corp. near Syracuse and a self-described history buff, Moreau says that when he drives through unfamiliar towns, he likes to know something about their history. A small GPS device got him thinking.

“I said to myself, ‘What if it told me something else about this town that we’re driving through? How would I take this device and modify it?’”

The result is GeoReader, an app for smartphones that provides historical narration about sites as you approach or pass them. Moreau is hoping to tap into the blossoming market for apps, specialized computer programs that have been developed to take advantage of the arrival of smartphones—Blackberries, iPhones, and Android-powered devices. Built for Google’s Android operating system, Moreau’s app combines the location technology of the built-in GPS in most smartphones, a database of “talking points,” and the phone’s ability to “read” text aloud.

GeoReader was a finalist in the 2010 European Satellite Navigation Competition, which recognizes the most innovative uses of satellite navigation.

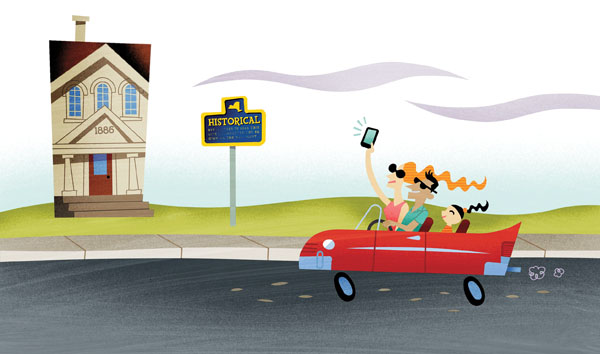

DRIVING PAST: Because it can be hard to read historical markers while driving, Moreau’s phone app, GeoReader, does it for you. (Photo: Adam Fenster)

DRIVING PAST: Because it can be hard to read historical markers while driving, Moreau’s phone app, GeoReader, does it for you. (Photo: Adam Fenster)After initial inspiration struck, Moreau turned his attention to his own smartphone, knowing that it had a built-in GPS, the ability to hold large quantities of data, and the ability to “read” data aloud. “I went online and started reading about how to make an app,” recalls Moreau. “And I quickly realized this was way beyond my personal capabilities.”

No matter. “I formed a little LLC,” he says. He explained the concept to programmers and hired them to do the technical work, while maintaining all the rights to GeoReader. Moreau maintains a website, www. mygeoreader.com, which contains an introduction to the app along with written instructions and a video demonstration.

As programmers were building the app, Moreau collected the information to place in the GeoReader’s database of talking points.

“I was befriending people who had websites that contained large amounts of data,” says Moreau. “And they graciously offered it to me to include in this app. I was able to get a lot of data as a starter set so no matter where you were in the country you could hear something.”

Moreau estimates that he edited between 30,000 and 40,000 bits of data into discrete, crisp talking points associated with specific sites or geographic coordinates. “I would do that every evening,” he says.

Moreau no longer shoulders that burden alone. The app allows users to enter talking points themselves and make them “public” to all GeoReader users. “Everybody is an expert in their local area. It definitely is designed to encourage people to contribute,” says Moreau.

A free application, GeoReader has made no money for Moreau; it’s been a net expense. Underscoring that point, Moreau says, “My plan is to launch it on the iPhone when I get enough funds.”

Moreau doesn’t envision GeoReader—primarily a labor of love—necessarily as a profitable venture.

Nonetheless, the Simon School graduate who credits that program with enhancing his problem-solving skills—“I felt like when I graduated I could handle almost any problem thrown at me”—notes he’s begun to court advertisers, whose messages could be activated on GeoReader much like talking points.

“Space in a high-traffic area is more valuable than in the middle of the woods,” he says. “But there’s value everywhere.”