Alumni Gazette

DANCE PARTNERS: Murray and Peggy Topf Schwartz (above), who met as students at Rochester, tell the story of Pearl Primus (opposite), a pioneering dancer and scholar, in their new book. “A lot of what she’d done had been forgotten” by the time the Schwartzes met Primus in 1981, says Murray Schwartz. (Photo: Stan Sherer)

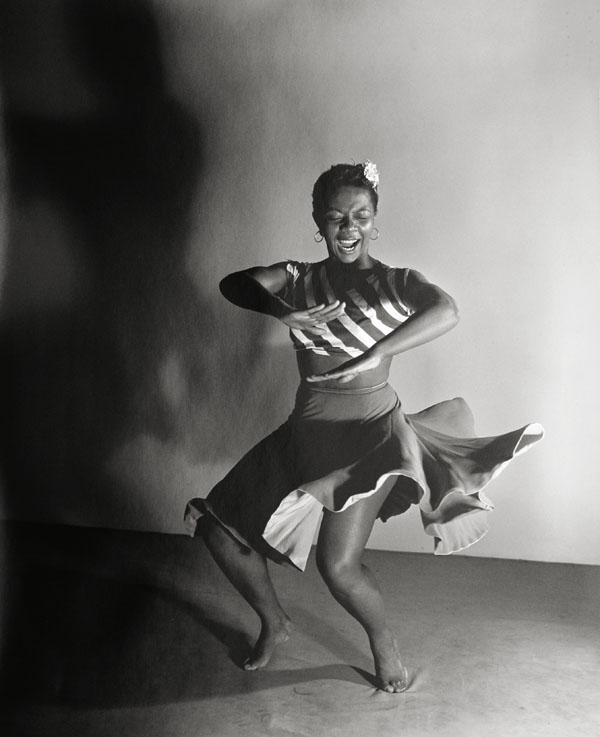

DANCE PARTNERS: Murray and Peggy Topf Schwartz (above), who met as students at Rochester, tell the story of Pearl Primus (opposite), a pioneering dancer and scholar, in their new book. “A lot of what she’d done had been forgotten” by the time the Schwartzes met Primus in 1981, says Murray Schwartz. (Photo: Stan Sherer) (Photo: Barbara Morgan/Courtesy of the University of Massachusetts Dance Program)

(Photo: Barbara Morgan/Courtesy of the University of Massachusetts Dance Program)It’s a premise for some good novels: A lead character or two, settled in their lives, have a life-altering encounter that sets the plot in motion.

It’s also a pretty accurate depiction of what happened to Murray ’64 and Peggy Topf Schwartz ’65 in the spring of 1981.

Murray was an English professor and dean at the State University of New York at Buffalo, when he came home to Peggy, the chair of the dance department at the Buffalo Academy for the Visual and Performing Arts, with a 30-page resume from Pearl Primus.

Primus was applying to become headmaster of SUNY Buffalo’s Cora P. Maloney College of Afro-American Studies. She also happened to be one of the most magnetic and pathbreaking figures in modern American dance. A dancer and scholar who eventually earned a doctorate in anthropology, Primus choreographed solo works that were deeply informed by her research in the American South as well as Africa and the Caribbean. But she had made her debut almost 40 years earlier and “a lot of what she’d done had been forgotten,” Murray recalls.

What Primus had done was to offer, through her solo dances, political commentary on racism and poverty that was radical for its time. Born in Trinidad and raised in New York City, she made her solo dance debut at New York’s 92nd Street Young Men’s Hebrew Association in 1943, with her dances “Strange Fruit” and “Hard Time Blues,” wrenching explorations of lynching and sharecropping.

That June, she performed at the Negro Freedom Rally, held at Madison Square Garden. And the following summer, she toured the American South, posing as a sharecropper and studying the communities whose lives she was intent on portraying through dance. These activities, along with her participation in communist and other left-wing organizations, attracted zealous attention from the FBI throughout the 1940s and early 1950s.

Murray hired Primus. It marked the beginning of a deep and enduring friendship between her and the Schwartzes that offers an added dimension to the Schwartzes otherwise scholarly work, The Dance Claimed Me: A Biography of Pearl Primus (Yale University Press, 2011).

Both admit that friendship with Primus, however rewarding, was not always easy. “She called Murray her angel and said it would be a lifetime assignment,” says Peggy.

Indeed it was. The friendship was marked by “frequent telephone calls, either early in the morning or at dinner time, surprise visits to Murray’s office or to our house, sometimes just to sit together quietly,” and many conversations about plans for performances, institutes, and academic exchanges, the Schwartzes write.

The idea for the biography came gradually, starting after Primus’s death from diabetes in the fall of 1994.

“Shortly after Pearl died,” Murray says, “Peggy, partly as an act of mourning, started to interview people who knew her—childhood friends, people in the dance world. Peggy spent years doing these interviews. Around 2004 or 2005, we realized we should team up.”

“We went to a little house we have in Vieques, Puerto Rico—500 square feet,” he says. “We sat at a table and we literally emailed chapters back and forth to one another. Peggy wrote drafts and I shaped them. And after a while, we couldn’t tell who had written what.”

Friendship with Primus came naturally to the Schwartzes, both of whom have embraced the arts and political activism their entire adult lives. They met at Rochester, where, Murray recalls, not only were they both studying English but “we were both in the honors program, which meant we had small seminars our junior and senior years.”

They married as students, and after Murray’s graduation, moved to Berkeley, where he pursued a doctorate in English and Peggy began working at a pilot Head Start program, designing a movement and dance program, while completing coursework toward her Rochester degree.

Peggy, who was raised in the Bronx and in Great Neck, N.Y., still remembers the shock she felt when, on a high school camping trip to the Smoky Mountains, she encountered the “Whites Only” and “Colored Only” signs that were posted at water fountains, restrooms, restaurants, and public places throughout the South in the late 1950s and early 1960s. “Growing up in New York, I had never seen anything like that,” she says. “My desire to be involved started in high school. Everything was just bubbling to the surface.”

DANCE SCHOLAR: An anthropologist as well as a dancer, Primus helped bring African dance to Americans. Her life crossed many boundaries, including ethnic, racial, and cultural, according to the Schwartzes’ new book. (Photo: Steve Long)

DANCE SCHOLAR: An anthropologist as well as a dancer, Primus helped bring African dance to Americans. Her life crossed many boundaries, including ethnic, racial, and cultural, according to the Schwartzes’ new book. (Photo: Steve Long)Murray, who grew up in Manhattan, Brooklyn, and Queens, says his father was active in the International Ladies Garment Workers Union, a magnet for Russian Jewish immigrants who had brought with them to the United States the secular socialist politics they developed in protest against the Russian Empire.

He speculates on what drew Primus to him and Peggy. “She trusted us to see what she was about. We were both so interested in taking an interdisciplinary approach to things.”

Peggy says that although Primus is known today almost exclusively in the dance field, her life crossed many boundaries—disciplinary as well as ethnic, racial, and cultural. And that made the prospect of writing the biography all the more enticing.

“We deliberately set out to make this book have a wide appeal,” she says. “Pearl’s life was so complex and rich. It touched on the civil rights movement, on the cultural history of New York City, and on the complicated relationship between blacks and Jews,” she says of Primus, who had a Jewish grandfather, was married briefly to the son of a Lower East Side Torah school principal, and participated in a number of organizations that joined New York’s black and Jewish political and cultural radicals.

In 1948, a trip to Africa financed by the Julius Rosenwald Foundation, transformed her life, and arguably, the scope of modern American dance.

“After she went to Africa, she was interested less in performing and more in teaching—on bringing authentic African dance to the United States,” says Murray. Peggy notes that after Primus’s return from Africa, she wore only African dress in public.

A dancer and scholar at a time before dance departments had become a mainstay at colleges and universities, Primus had to rely heavily on her allies in administration. In 1983, when the Schwartzes moved to Massachusetts, Primus followed a year later. Peggy was to join the Five College Dance Department, a collaborative program of the four western Massachusetts colleges of Amherst, Hampshire, Mount Holyoke, and Smith, and the University of Massachusetts. Murray was to become dean of humanities and fine arts at the University of Massachusetts, where he continued as Primus’s ally, but where she could only secure a string of temporary appointments.

“Dance didn’t really have an institutional base,” says Murray. “By the time she entered the academic world, it was just starting to gain a foothold.”

That’s something the Schwartzes have both found regrettable. Dance, as well as music, says Murray, “underlies all the other arts because they engage the rhythms of the body.”

That might be precisely the problem, Peggy speculates. Unlike art or music, she notes, “dance still has to justify itself as an academic discipline. It’s the Puritan culture that still doesn’t know how to deal with the body.”