In Review

ROOM FOR ALL: Rochester research underscores the importance of accepting workplaces and other social settings. (Photo: Steve Boerner for Rochester Review)

ROOM FOR ALL: Rochester research underscores the importance of accepting workplaces and other social settings. (Photo: Steve Boerner for Rochester Review)Coming out as lesbian, gay, or bisexual increases emotional well-being even more than earlier research has indicated, but the psychological benefits of revealing one’s sexual identity—less anger, less depression, and higher self-esteem—are limited to supportive settings, says a study coauthored by Richard Ryan, professor of psychology, and published in Social Psychology and Personality Science. The study, which included participants from 18 to 65 years old, found that age made no difference in who comes out, nor did gender or sexual orientation. Instead, the key determinant for revealing a minority sexual orientation was the supportiveness of the environment. “The vast majority of gay people are not out in every setting,” says Ryan. “People are reading their environment and determining whether it is safe or not.”

Brush and Floss for a Healthy . . . Heart?

Scientists have discovered the tool—a collagen-binding protein called CNM—that bacteria normally found in our mouths use to invade heart tissue, causing a dangerous and sometimes lethal infection of the heart known as endocarditis. A bacterium best known for causing cavities, Streptococcus mutans lives in dental plaque, churning out acid that erodes the teeth. A dental procedure of even vigorous flossing can allow the bacteria to enter the bloodstream. Although the immune system usually destroys them, occasionally—and within just a few seconds—they can travel to the heart and colonize its tissue, creating a potentially deadly infection. Microbiologist Jacqueline Abranches, a research assistant professor, is corresponding author of the study, published in Infection and Immunity. The research raises the possibility of creating a screening test to gauge a dental patient’s vulnerability to the condition.

Doves and Hawks, Hatched by Stress

Is your child a “dove,” cautious and submissive when confronting new environments? Or perhaps you have a hawk, bold and assertive in unfamiliar settings? Those basic temperamental patterns are linked to opposite hormonal responses to stress—differences that may provide children with advantages for navigating threatening environments, researchers report in Development and Psychopathology. “Divergent reactions—both behaviorally and chemically—may be an evolutional response to stress,” says Patrick Davies, a professor of clinical and social psychology and lead author of the study, noting that each technique may work better in certain family conditions. “When it comes to healthy psychological behavior, one size does not fit all,” says coauthor Melissa Sturge-Apple, an assistant professor of clinical and social psychology.

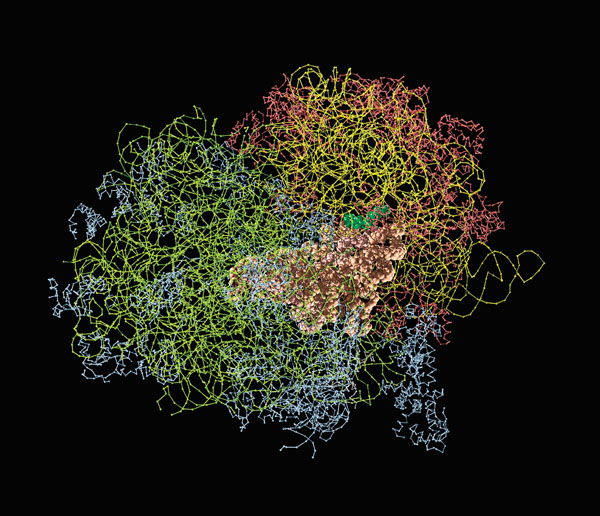

TAKE A MESSAGE: Model of a ribosome, which uses instructions provided by messenger RNA to build proteins. (Photo: iStockPhoto)

TAKE A MESSAGE: Model of a ribosome, which uses instructions provided by messenger RNA to build proteins. (Photo: iStockPhoto)Changing a Genetic ‘Red Light’ to Green

In a study published in the journal Nature, scientists discovered an entirely new way to change the genetic code, overriding an errant form of genetic signaling for the first time. The findings, though early, are significant because they may ultimately help researchers alter the course of devastating genetic disorders such as cystic fibrosis, muscular dystrophy, and many forms of cancer. The genetic code is the set of instructions in a gene that tells a cell how to make a specific protein. Central to the body’s protein production process is messenger RNA, which takes instructions from DNA and directs the steps necessary to build a protein. For the first time, researchers modified messenger RNA and in doing so changed the original instructions for creating the protein. The end result: a different protein than originally called for. Yi-Tao Yu, an associate professor of biochemistry and biophysics, is lead study author. Robert Bambara, chair of the department, says that the “ability to manipulate the production of a protein from a particular gene is the new miracle of modern medicine.”

A Potent Illusion

Scientists have come up with new insight into the brain processes that cause an optical illusion. Jump off a treadmill and everything seems for a moment to be in motion; similarly, as a dartboard design moves, with the lines seemingly moving toward the center, an interspersed image of Rochester mascot Rocky seems to loom forward. But it’s an illusion, caused by the way our brains have adapted to the inward motion of the background, which becomes a new status quo. Called the Motion Aftereffect, and first documented by Aristotle—minus Rocky—the phenomenon is caused by neural processes that occur whenever we see moving objects, according to brain and cognitive sciences doctoral student Davis Glasser. A study he conducted with advisor Duje Tadin, an assistant professor of brain and cognitive sciences, and colleagues at the Montreal Neurological Institute, was published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Diabetes and Obesity Are a Daunting Duo for Pregnancy

Type 2 diabetes and obesity in pregnancy together raise a major red flag, according to new research published in the Journal of Maternal-Fetal and Neonatal Medicine. The study shows that both conditions independently contribute to higher risks, opening the door to a wide range of pregnancy, delivery, and newborn complications. Obesity and type 2 diabetes are skyrocketing in women of childbearing age; the Journal of the American Medical Association reports that between 2007 and 2008, the prevalence of obesity among adult women in the United States was more than 35 percent, while the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention say that about 11 percent of women over age 20 had diabetes in 2010. “We’ve never seen the degree of obesity and type 2 diabetes in women that we are seeing right now, because for a very long time diabetes was a disease of an older population,” says senior study author Loralei Thornburg, an assistant professor of obstetrics and gynecology.