Alumni Gazette

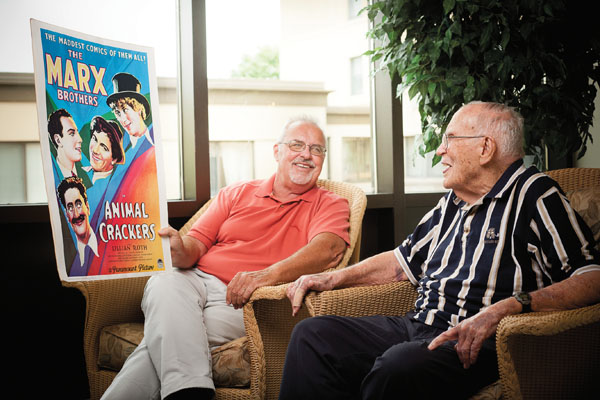

FILM FANS: Films featuring the Marx Brothers were among a collection of 16-millimeter films that Bob and Herbert Tindall donated

to the University along with rare footage of the River Campus. (Photo: Dave Londres for Rochester Review)

FILM FANS: Films featuring the Marx Brothers were among a collection of 16-millimeter films that Bob and Herbert Tindall donated

to the University along with rare footage of the River Campus. (Photo: Dave Londres for Rochester Review)Last November, Joanne Bernardi, an associate professor of Japanese who also teaches in Rochester’s film and media studies program, found a welcome surprise in her email inbox.

It was a message from Bob Tindall ’65, who had read about her course, Atomic Creatures: Godzilla (“History in Celluloid,” Rochester Review, November-December 2010). The owner of a large private film collection, he asked her if she would be interested in an original, 16-millimeter film print of King Kong. Two days later, after an extended email dialogue, Tindall wrote to Bernardi that he was willing to donate his entire collection to the University.

The commercial films in the collection—classics by W. C. Fields, the Marx Brothers, and Abbot and Costello, for example, all in 16 millimeter—were impressive enough. But what made the collection even more valuable to the University was footage of the River Campus shot by Herbert Tindall ’36, Bob’s father, in 16-millimeter film between 1932 and 1940, the graduation year of Herb’s younger brother, Harry.

“The film shot by [Bob’s] father is, literally, priceless,” says Bernardi. “Sixteen millimeter was introduced by Kodak here in Rochester in 1923, which makes him a ‘first generation’ 16-millimeter filmmaker.”

Nancy Ehrich Martin ’65, ’94 (MA), a classmate of Bob’s and now the John M. and Barbara Keil University Archivist, calls the film, which is now accessible to viewers in DVD format, “remarkable.”

“When Herb arrived as a freshman, the campus was practically brand new,” she says. “He was entering an infant physical campus.”

The film, not so much titled as labeled (“University of Rochester, 1932–1940”), is rich in content, including classroom scenes, sports competitions, and the everyday clowning around of a sharply dressed crop of male undergraduates (women remained at the Prince Street Campus until 1955). Most striking, from an early 21st-century standpoint, say Martin, Bernardi, and others who have viewed the DVD, is not only the homogeneity of the virtually all-white faculty and student body, but the attire: ties and vests to class, to lab, and it seems, everywhere except on the basketball court or the football field.

Today, Herb lives in Lancaster County, Pa., where he spent most of his working life as a country doctor. Bob and his wife, Janice Clough Tindall ’66, live about 20 miles from Herb. To offer people a sense of his dad’s passion for film, Bob has a story he likes to tell.

“My mother was pregnant with her first-born child, which was me. When she went to the hospital to have me, he checked her in, and much to my mother’s dismay, he went to the movies. And while he was at the movies, I was born.”

It’s an account Herb disputes.

“No, no,” he says. “I was there for the delivery.”

“Oh, listen to this,” Bob retorts. (The film, he adds, was You’re in the Army Now.)

Herb developed an interest in photography and film as a high school student, outside Philadelphia, in the 1920s. “There was a group of us,” he says. “We had our own photo-finishing operation. We went around to summer camps and got the kids film so we could process it for them.”

In the late 1920s, he purchased a Kodak Model B—a boxy, 16-millimeter motion picture camera introduced by the Eastman Kodak Co. in the late 1920s—and began making home movies.

At the same time, he nurtured his interest in commercial motion pictures by renting and showing them at home to friends. “There was a place downtown, in Philadelphia, where they had a whole collection of old 16-millimeter films, all silent, of course,” he says. “You could rent a picture every week for $50 a year. That’s what we did,” he says. “It sounds like a lot, but it’s only a dollar a picture.”

Herb says it was a coincidence that he went to college in the hometown of Kodak. The son of a salesman for the Remington Typewriter Co., he moved around a lot, and his father had recently been transferred to Remington’s Rochester office. (“Before I started at Rochester,” Herb adds, “he was transferred to Chicago.”)

After college, medical school, and service in the Navy, Herb established a medical practice and lived with his wife, Julie—to whom he was married from 1941 until her death in 1994—and their four kids on a farm in Lancaster County. He continued the tradition of opening his home, and his expanding film collection, to the community.

Bob says the films, shown decades before the availability of VHS videotapes and VCRs, were well-attended and treasured by his father’s many friends. And to illustrate just how much, Bob has another story.

Several months ago, he says, “My stepmother died. And at her funeral, I can’t tell you how many people came up to Dad and said to him, ‘I remember watching the movies at your farm.’ Not that he did this or that. But that he had opened up the farm for people to come and watch these movies.”

“Movies are a sociological phenomenon,” he continues. “They involve other people. You can sit locked in your room watching a movie that’s shown on a projector. But not a lot of people do that. The point of movies is to engage the community.”