Features

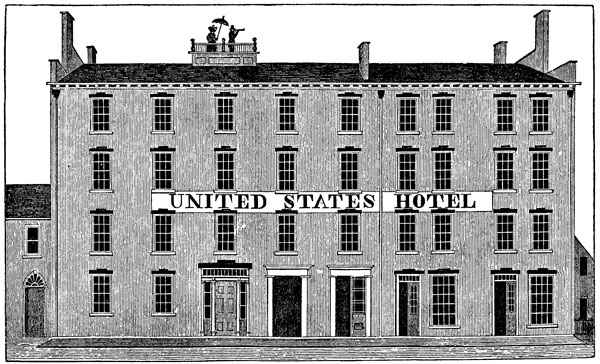

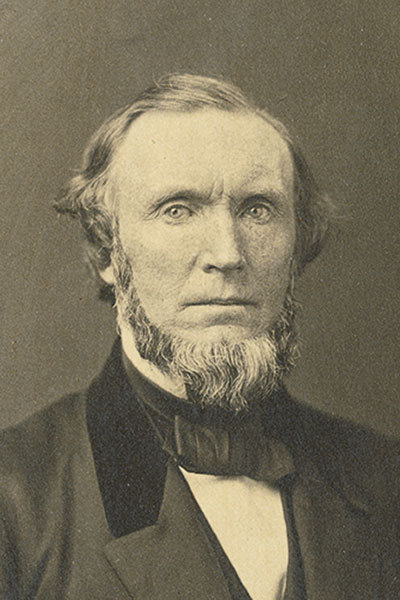

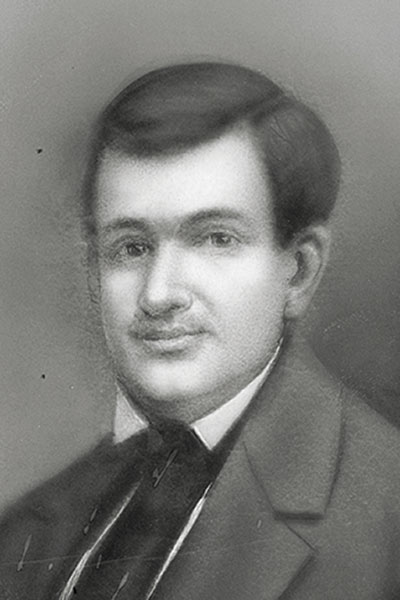

EARLY DAYS: Founding trustee John Wilder (below, left) and then President Martin Brewer Anderson were key early figures as the University set up its “campus” in the United States Hotel in Rochester. (Photo: University Libraries/Department of Rare Books, Special Collections, and Preservation)

EARLY DAYS: Founding trustee John Wilder (below, left) and then President Martin Brewer Anderson were key early figures as the University set up its “campus” in the United States Hotel in Rochester. (Photo: University Libraries/Department of Rare Books, Special Collections, and Preservation)Since its earliest days housed in the United States Hotel building on Rochester’s West Main Street in the 1850s to its stature today as one of the nation’s premier research universities, Rochester has grown in size and influence. Helping lay the groundwork for the standard model of matter, the country’s first educational program in optics, one of the nation’s most highly regarded music schools, pioneering work in vaccine technology—the list of the ways that Rochester has made, and continues to make, a lasting imprint on the world is long. But none of its achievements would be possible without the engagement of the University community to make Rochester “ever better.”

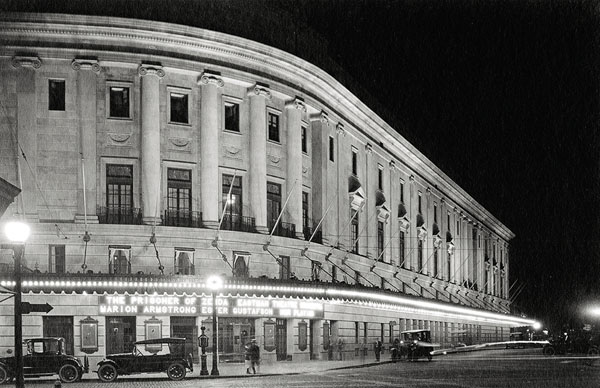

COMMUNITY LEGACY: Eastman Theatre opened in 1922. (Photo: University Libraries/Department of Rare Books, Special Collections, and Preservation)

COMMUNITY LEGACY: Eastman Theatre opened in 1922. (Photo: University Libraries/Department of Rare Books, Special Collections, and Preservation)No history of giving at Rochester could be complete without including George Eastman, the founder of the Eastman Kodak Company and Rochester’s most generous and influential donor.

(Photo: University Libraries/Department of Rare Books, Special Collections, and Preservation)

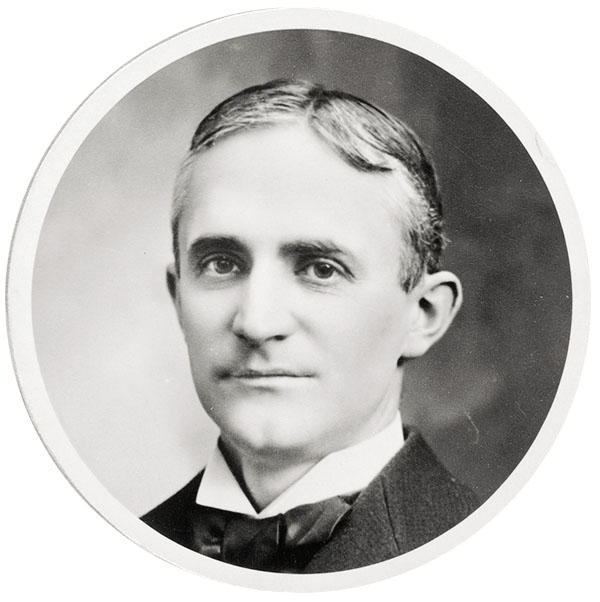

(Photo: University Libraries/Department of Rare Books, Special Collections, and Preservation)In 1899, Eastman gave the University his first gift: a Cartridge Kodak #5 camera, donated to a geology professor to enable him to take photographs on glass plates or film. Over the years, as Eastman’s relationship with the University and its third president, Rush Rhees, grew, so did his vision for Rochester’s future.

In 1902, Rhees approached Eastman for the first time to ask for a contribution, explaining the University’s need for a physics and biology building. Eastman offered $5,000, but admonished Rhees that “I am not interested in higher education.” Ultimately, however, he decided to give Rhees a check for $60,000—the entire cost of the building. When the three-story, red-brick building opened in 1906, the ever-modest Eastman was chagrined to see it named in his honor.

His skepticism about the value of education was not to last. The “progress of the world depends almost entirely upon education,” he came to declare in 1924, and Rochester was an institution in which he had “unbounded confidence.” Shortly before he died in 1932, Eastman revised his will to leave most of the balance of his estate, valued then at more than $17.6 million, to the University.

PARTNERS: George Eastman (left), with Rush Rhees (Photo: University Libraries/Department of Rare Books, Special Collections, and Preservation)

PARTNERS: George Eastman (left), with Rush Rhees (Photo: University Libraries/Department of Rare Books, Special Collections, and Preservation)In the past 161 years, the University has grown to 158 buildings, more than 200 academic majors, and more than 2,000 faculty and instructional staff. At every juncture, members of the University and Rochester communities have come together to provide for the institution’s future. Here are a few sample moments in the University’s philanthropic history.

1850

(Photo: University Libraries/Department of Rare Books, Special Collections, and Preservation)

(Photo: University Libraries/Department of Rare Books, Special Collections, and Preservation) (Photo: University Libraries/Department of Rare Books, Special Collections, and Preservation)

(Photo: University Libraries/Department of Rare Books, Special Collections, and Preservation)In 1849, sponsors of an earlier plan to relocate Madison University—now Colgate—from Hamilton, N.Y., to Rochester applied to the regents of the University of the State of New York for a provisional charter to establish an entirely new institution of higher learning in the Flour City. The regents issued the charter on Jan. 31, 1850, with the stipulation that the charter would expire if plans to raise $130,000—three-quarters of which would form a permanent endowment—were not realized. The ensuing campaign for funds took supporters of the would-be college throughout the state. Newspaper publisher Alvah Strong later wrote in his autobiography: “I myself went with Messrs. [John] Wilder and [William] Sage . . . from store to store and from house to house, in city and country, soliciting subscriptions to the University.” Wilder, an Albany businessman who had promoted Madison’s move, moved to Rochester in 1849 and, elected president of the Board of Trustees, took the reins of the fundraising effort. In 1861, the regents declared the charter to be permanent.

1900

(Photo: University Libraries/Department of Rare Books, Special Collections, and Preservation)

(Photo: University Libraries/Department of Rare Books, Special Collections, and Preservation)When, after a long effort by supporters of women’s education, Rochester trustees approved a plan to make the University coeducational, they did so on the condition that $100,000 first be collected to fund the expansion of the student body. “Glory, Hallelujah!” proclaimed Susan B. Anthony. “This is better news to me than the victory over Spain. It is a peace-victory, achieved only by the death of prejudice and precedents.” Rochester women—led by Helen Montgomery, a graduate of Wellesley College and cofounder, with Anthony, of the Women’s Educational and Industrial Union of Rochester—embarked on a door-to-door campaign across the city. But the required amount of money was large, and after two years the committee still fell short, with only $40,000 to show for their efforts. In June 1900, the trustees were persuaded to lower the stipulated amount to $50,000 in subscriptions—a total that was dramatically achieved when Anthony pledged her own life insurance to cover the final $2,000 needed.

1920s

MODERN MEDICINE: Early School of Medicine and Dentistry professor George Corner leads an anatomy class. (Photo: University Libraries/Department of Rare Books, Special Collections, and Preservation)

MODERN MEDICINE: Early School of Medicine and Dentistry professor George Corner leads an anatomy class. (Photo: University Libraries/Department of Rare Books, Special Collections, and Preservation)The Eastman School of Music, the School of Medicine and Dentistry, Eastman Institute for Oral Health, Strong Memorial Hospital, the River Campus—all trace their roots to the civic-minded leadership, vision, and support of Eastman Kodak founder George Eastman and a remarkably transformative period in the 1920s. Working with then President Rush Rhees, Eastman began his “great music project,” eventually committing $17 million to support the music school and to build Eastman Theatre. Also with Rhees and with the support of what’s now the Rockefeller Foundation, Eastman led efforts to establish an innovative “model medical school,” where physicians would train in science as well as in clinical care at the adjacent Strong Memorial Hospital (named for Eastman’s business partner, Henry Alvah Strong). Spurred by his own dental woes, Eastman insisted that the new school include dentistry. In the early 1920s, when it became clear that the University was outgrowing its Prince Street location, trustees embarked on a plan to move the College for Men to a bend in the Genesee River. Alumni and others—notably Joseph Alling, Class of 1876, president of the associated alumni—called on the University to look beyond securing its immediate needs and launch an ambitious campaign to provide for its future. Dubbed “Ten Millions in Ten Days,” the effort—begun in November 1924—garnered the participation of more than 10,000 subscribers. More than 70 percent of living alumni, along with faculty and students, also contributed. The campaign’s major single contributor was Eastman.

1950s

MODELING: President Cornelis de Kiewiet, in a photograph taken by Ansel Adams in 1952. (Photo: University Libraries/Department of Rare Books, Special Collections, and Preservation)

MODELING: President Cornelis de Kiewiet, in a photograph taken by Ansel Adams in 1952. (Photo: University Libraries/Department of Rare Books, Special Collections, and Preservation)One of the first challenges taken on by Cornelis de Kiewiet as president was the merging of the men’s and women’s colleges on the River Campus—a merger that brought with it a need for new funds to provide new facilities, such as a six-story residence to house the women who had previously lived on the Prince Street Campus, and other living, dining, and athletic facilities for men and women. The 18-month, $10.7 million campaign took as its theme: “A truly great U. of R. benefits us all. Will you help?” Advertisements filled newspapers, store windows, billboards, and buses. In January 1956, the campaign surpassed its target, with a total of $12 million.

1960s

GROUNDBREAKING: Board Chair Joseph Wilson ’31 (right) helped guide the University’s growth in the 1960s with president W. Allen Wallis (third from left). In the early 1960s, the two celebrated the groundbreaking of a nuclear structure laboratory with Rochester Gas & Electric CEO Robert Ginna (left), and physics professor Harry Gove. (Photo: University Libraries/Department of Rare Books, Special Collections, and Preservation)

GROUNDBREAKING: Board Chair Joseph Wilson ’31 (right) helped guide the University’s growth in the 1960s with president W. Allen Wallis (third from left). In the early 1960s, the two celebrated the groundbreaking of a nuclear structure laboratory with Rochester Gas & Electric CEO Robert Ginna (left), and physics professor Harry Gove. (Photo: University Libraries/Department of Rare Books, Special Collections, and Preservation)Of the University’s dramatic rise in the 1960s under the leadership of then Board of Trustees Chair Joseph Wilson ’31, then President W. Allen Wallis noted the Xerox founder’s vision in shaping Rochester’s future: “[H]e inspired others to do it. He elevated everybody’s sights.” While Wilson and his family gave generously in support of brick-and-mortar improvements, their most heartfelt gifts were for less tangible purposes. With his parents and his wife, Marie, Wilson gave his “first great gift,” in Wallis’s words, to be spent in five years “on people and programs, not things.” The most substantial gift from him and his wife, a contribution of $15 million in 1967, was intended particularly for distinguished professorships. In a letter announcing the gift to Wallis, Wilson wrote: “There is no doubt that the University needs buildings desperately, and Peggy and I are delighted that we could help with that. But helping to improve the intellectual quality of the academic programs that go into those buildings is very close to our hearts indeed, and truly an exciting prospect for us.” In the late 1960s that vision also took shape as the University developed plans to accommodate an eightfold increase in faculty and students since the River Campus opened in 1930. A $38 million fundraising effort made possible the construction of some of Rochester’s signature structures—Wilson Commons; the Interfaith Chapel; the addition of the east wing on Rush Rhees Library; Hutchison Hall—as well as new facilities at the Medical Center, an enlargement of Sibley Library, and additional practice rooms and other improvements at the Eastman School.

1990s

HEAR YE: Robert Goergen ’60, then chairman of the Board of Trustees, rings the Anderson Bell to signal the official opening of the campaign victory celebration for the “Campaign for the ’90s.” (Photo: University Libraries/Department of Rare Books, Special Collections, and Preservation)

HEAR YE: Robert Goergen ’60, then chairman of the Board of Trustees, rings the Anderson Bell to signal the official opening of the campaign victory celebration for the “Campaign for the ’90s.” (Photo: University Libraries/Department of Rare Books, Special Collections, and Preservation)A five-year, $375 million “Campaign for the ’90s” concluded in June 1996 with a final tally of $421 million—$46 million over the goal. More than $303 million came from outside the Rochester area, an indication of growing national standing. “Campaigns create resources, and resources create new possibilities, new options, for people at the University,” Robert Goergen ’60, then chair of the Board of Trustees, told supporters at a victory celebration. He made one of the campaign’s largest individual gifts, $10.5 million, $10 million of which established an endowment for undergraduate programs. More than 78,000 donors contributed to the campaign chaired by Edwin Colodny ’48 and David Kearns ’52.

The Medical Center made a major commitment to medical research in the 1990s with a plan to modernize its research facilities and recruit 70 research scientists and 400 technicians and support personnel by investing $400 million over 10 years—the largest effort since the School of Medicine and Dentistry opened in 1925. As part of a strategic plan to strengthen Rochester’s work in understanding and curing diseases and to enhance its reputation among the country’s top programs, the Medical Center launched the “Campaign for Discovery” in 1997, an effort to raise $35 million in five years. In just two and a half years, the goal was achieved, with more than $25 million in contributions coming from the Rochester-area community. The Arthur Kornberg Medical Research Building—named in honor of Arthur Kornberg ’41M (MD), who received the Nobel Prize in 1959 for unraveling the process of DNA replication and for his work as the first scientist to synthesize DNA in the laboratory—and the Aab Institute for Biomedical Science are among the fruits of the campaign.

For more on University of Rochester history, see A History of the University of Rochester, 1850–1962 by Arthur May (University of Rochester Press, 1977), the source of much of the information in this article.