Alumni Gazette

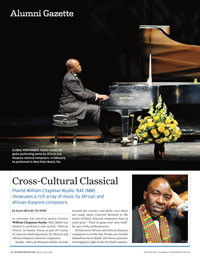

GLOBAL PERFORMER: Nyaho travels the globe performing works by African and diaspora classical composers. In February, he performed

in West Palm Beach, Fla. (Photo: Steve Mitchell/AP Images for Rochester Review)

GLOBAL PERFORMER: Nyaho travels the globe performing works by African and diaspora classical composers. In February, he performed

in West Palm Beach, Fla. (Photo: Steve Mitchell/AP Images for Rochester Review) (Photo: Steve Mitchell/AP Images for Rochester Review)

(Photo: Steve Mitchell/AP Images for Rochester Review)In January, the Seattle-based pianist William Chapman Nyaho ’84E (MM) was invited to perform a solo recital, “African Voices,” in Austin, Texas, as part of a series of concerts featuring music by African and African diaspora classical composers.

Nyaho, who’s performed similar recitals around the country and globe, says there are many more concerts devoted to the music of black classical composers than in years past. “They’ve gone over very well,” he says of the performances.

If interest in African and African diaspora composers is on the rise, Nyaho can include himself as one to thank. He’s been a pioneer in bringing to light works by black composers that have sat in manuscript form—never published, much less performed or recorded—in archives around the world.

He’s spent several years seeking out unpublished and out-of-print works, and over 2007 and 2008, completed a five-volume sheet music anthology, Piano Music of Africa and the African Diaspora, published by Oxford University Press.

“Part of this project has been to create demand—to have people check this music out and go research, go look,” says Nyaho.

Another goal of the anthology was to make the music accessible at colleges and universities where much of the classical music canon is instilled and taught over generations.

“I wasn’t aware of all this music when I was even at Eastman,” says Nyaho, who studied with master pianists Barry Snyder ’66E, ’68E (MM) and David Renner ’60E, ’65E (MM).

The Eastman School has seen a few prominent black composers cross its path. George Walker ’56E (DMA), whose works include Piano Sonata No. 2, which he completed as his doctoral dissertation, won a Pulitzer Prize in music in 1996 for his composition Lilacs, for voice and orchestra.

And Howard Hanson, director of the Eastman School from 1924 to 1964, took a strong interest in contemporary composers, including African-Americans Ulysses Kay ’40E (MM), a student of Hanson’s, and William Grant Still, whose Afro-American Symphony Hanson included in a Rochester Philharmonic concert in 1931. It was the premiere of the symphony and the first time a major orchestra had performed the work of a black composer.

But Nyaho’s volumes, arranged according to the level of difficulty of the music, include works by an exceptionally diverse group, geographically and musically, both living and dead, from Egypt to South Africa, to Cuba, Haiti, and the United States.

The anthology was widely praised in Europe. A reviewer for the British classical music magazine Musical Opinion declared, “Technically accomplished pianists seeking to develop their hands, ears, and imagination in new ways, and to take their audiences on voyages of discovery, are recommended to obtain these volumes at the earliest opportunity.”

Born in the late 1950s in Washington, D.C., where his father was serving as the first ambassador to the United States of a newly independent Ghana, Nyaho grew up in a musical household in Accra, where he was surrounded by Western classical music as well as two quite distinct native “musics.”

“My parents came from two different ethnic groups, and their music—the harmonies were different, the melodic content was different, everything was really quite different,” says Nyaho.

Nyaho has performed some of his favorite piano works by African and African diaspora composers on two CDs—Senku, released in 2003, and Asa, released in 2008, both by MSR Classics. Both recordings include multiple premieres.

Nyaho points out that non-Western themes aren’t new in classical music—or “art music,” a term he also uses to signify the historical and geographical breadth of music rooted in the European classical tradition. Béla Bartók and Antonín Dvořák, for example, incorporated non-Western influences into their compositions. The key difference between them and black composers who have melded Western and non-Western traditions, says Nyaho, is that Bartók and Dvořák are part of the recognized musical canon, and composers such as the African American Margaret Bonds, or the Jamaican Oswald Russell, aren’t.

His hope is that “people will be aware of this music that is out there, that is just as important—and as phenomenal—as the music we hear from Bach to Beethoven to Brahms.”