Alumni Gazette

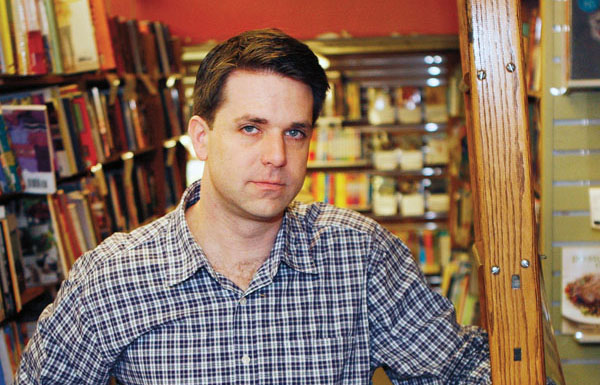

BAFFLING & BELIEVING: “The nice thing about The Baffler is that you could read it, and you didn’t have to believe in any one kind of program,” says Summers. (Photo: Bizuayehu Tesfaye/AP Images for Rochester Review)

BAFFLING & BELIEVING: “The nice thing about The Baffler is that you could read it, and you didn’t have to believe in any one kind of program,” says Summers. (Photo: Bizuayehu Tesfaye/AP Images for Rochester Review)The return of The Baffler has set the blogosphere abuzz.

For a magazine that appeared only occasionally, The Baffler made a big splash in its brief heyday in the 1990s.

From its founding by Harper’s columnist Thomas Frank in 1988, until late 2010, it came out only 18 times—and just twice in the past decade.

Called “the journal that blunts the cutting edge,” The Baffler’s fan base included some of the most prolific and well-known figures in contemporary American letters.

In late 2010, Frank, the Kansas native who penned the 2004 bestseller What’s the Matter with Kansas?, conceded he’d be unable to sustain the journal. He called his friend and loyal Baffler contributor Chris Lehmann ’89 (MA) to seek advice.

“Tom called me in a dejected state,” says Lehmann, a veteran journalist who’s editor of Bookforum and formerly a managing editor at Yahoo News. “He said, ‘I can’t run this magazine anymore. Do you know anyone who might want to take over a political and literary journal, and is in a position to?’ That was probably the only time in my life when I was able to answer ‘yes’ to a question like that.”

John Summers ’06 (PhD) had paid Lehmann a visit in 2010. The two had known one another since the late 1990s when Summers, then a graduate student in history at Rochester, had invited history alumnus Lehmann to campus to deliver a talk. Summers had been planning to spearhead a new literary journal and sought Lehmann’s support.

Lehmann gave it. But after Frank called, he had new advice for Summers. “I said, ‘You can launch a brand new literary journal in a climate that’s not exactly ideal for publication launches, or you could take over this well-recognized brand within the same space you want to occupy.’”

When Summers received a phone call from Frank, “about five minutes into the phone call I said yes,” Summers says.

This March, The Baffler returns under Summers’s leadership as editor-in-chief and with a $500,000 publication contract with MIT Press to ensure the journal’s continuation and publication on a regular schedule for the next five years.

“It’s the largest deal in the history of MIT Press’s arts and humanities publishing,” says Summers, who adds that the journal, which boasts a Web, Facebook, and Twitter presence, will be available “on every digital platform.”

Lehmann, who’s senior editor of the revived Baffler, admits he’s amazed. “They were constantly trying to find some reliable funding stream,” Lehmann says of Frank and the other Baffler stakeholders. “He’s been amazing,” Lehmann says of Summers’s negotiation of the MIT Press contract. “For The Baffler, this is a huge breakthrough.”

The Baffler specializes in long-form journalism, each issue anchored by an essay of as many as 10,000 words. While it’s decidedly left-wing in its orientation, it’s not aimed at promoting any particular political program. Its defining characteristic is a relentless commitment to upending the ingrained—and in the view of Baffler editors, misguided—assumptions of political and economic elites of both major political parties, the media, and corporate boardrooms.

“The nice thing about The Baffler is that you could read it, and you didn’t have to believe in any one kind of program,” says Summers. “They weren’t socialists, or they weren’t anarchists, or they weren’t New Deal liberals, or 19th-century populists. They were a little bit of all of those things,” he says of past Baffler writers.

The March issue features “Of Flying Cars and the Declining Rate of Profit,” an essay in which anthropologist David Graeber (a key planner of the Occupy Wall Street protests) argues that by many measures, we are living in a time of markedly slow progress in technological innovation.

Frank contributes “Too Smart to Fail: Notes on an Age of Folly,” in which he argues that “a résumé filled with grievous errors in the period 1996–2006” is not only forgiven, but a virtual prerequisite to being taken seriously in Washington today.

Additional essays by bestselling authors Barbara Ehrenreich and Rick Perlstein, as well as a section of fiction, poetry, and satirical art, round out the journal.

Summers is optimistic he can maintain, and even broaden The Baffler’s appeal. “Free market dogma is our sweet spot, wherever it is,” he says. Since the economic collapse of 2008, it’s hard to say there isn’t a market for criticisms of the free market.

It’s not just The Baffler that’s experiencing a big break, but Summers himself. Like many younger humanities scholars, he’s been without a full-time job, in his case despite stints as a part-time instructor at Harvard, Columbia, and Boston College, and multiple publications. He wrote an essay, “Gettysburg Regress,” which the late Christopher Hitchens included in The Best American Essays of 2010 (Mariner Books). He’s edited two collections of essays—one by the critic Dwight MacDonald, and another by the radical sociologist C. Wright Mills, both of which earned him attention in outlets such as the New York Times and the New York Review of Books. He’s published a collection of his own essays, Every Fury on Earth (Davies Group,) and won a coveted publishing contract from Oxford University Press for his forthcoming biography of Mills, based on his dissertation in history at Rochester.

But, he says, “I didn’t write a dissertation that was calculated to try to favorably impress a hiring committee. I ended up writing a dissertation about a dead, white, male anarchist, in the form of a biography, which is just about the worst set of calculations you can make.”

He credits his mentors at Rochester for permitting him “the intellectual freedom to explore lots of different traditions. I’m very grateful for that. I’m grateful that I wasn’t told that I wasn’t allowed to write for the newspapers or for magazines,” he says, referring to members of the academy who discourage students from writing for nonacademic audiences.

Going from writer to editor means, of course, that he’ll be responsible for maintaining the journal’s voice. To keep it as brash and uncompromising as its readers have come to expect, he’ll need editorial independence.

As he continues to seek backers, he promises he’ll have it. From MIT Press, he’s got it. Says Summers: “It’s written in my own blood in the contract.”