Features

(Photo: University Libraries/Department of Rare Books, Special Collections, and Preservation)

(Photo: University Libraries/Department of Rare Books, Special Collections, and Preservation)October 9, 1976

Rochester, N.Y.

My dear young man,

It is, I think, salubrious and worthwhile for us all to meditate, from time to time, on the great theme of mutability and transience, to mortify our overweening vanity, and to say with the preacher, ‘What profit hath a man of all his labour, . . .’ and so forth. What, after all, is Fame? And what, Celebrity? Fleeting evanescences, mere toys and illusions. I know you will think this simple modesty in me, and dismiss it with a casual wave of the hand. But when you attain to my age and gravity, you will know that some of those goals, which in your youth seemed the only possible or valuable target upon which attention could seriously be fixed, turn out in the end to be gossamer-friendly or utterly illusory. What are we, after all, but a handful of dust, if I may thus express myself?

So wrote the poet Anthony Hecht to his friend William MacDonald, an archaeological historian. The letter concerned Hecht’s purchase of a book in the University of Rochester bookstore—on the remainder shelf, at a steeply reduced price. The book had been a classic in Roman history, and in his musings to MacDonald, with whom he enjoyed especially colorful exchanges, the eminent poet expressed the anxieties born of acclaim with his characteristic wit and rhythmic prose. Even the decision to purchase the book, he described with a flourish.

I sighed the sigh of Heraclitean Flux, and a tear from the depths of some divine despair, of which Tennyson speaks, rose to my eye. But I bought it, and took it home.

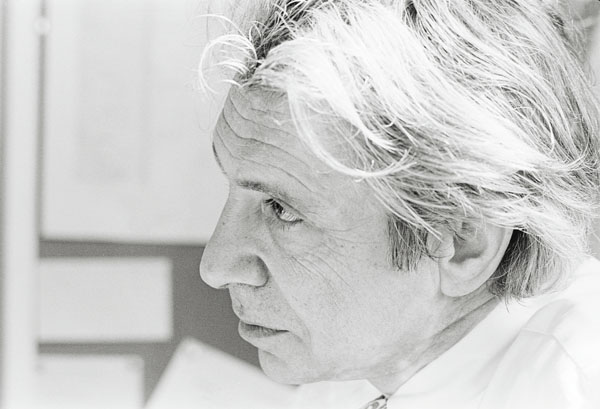

Anthony Hecht taught at the University for 18 years, 17 of them as the John Hall Deane Professor of Rhetoric and Poetry. Beginning in the 1950s, largely due to the efforts of Hyam Plutzik, who became the first John Hall Deane Professor of Rhetoric and Poetry, the English department had begun to build a culture around poetry writing and performance. In the fall of 1967, when Hecht arrived in Rochester to help continue that tradition, he was already a well-regarded poet.

Then, the following spring, he won the Pulitzer Prize for his second book of poetry, The Hard Hours. Whereas the Pulitzer might have been the capstone of his career, it was more a midpoint. He would receive the prestigious Bollingen Prize in 1973, be named the U.S. Poet Laureate in 1982, and publish five more collections of poetry and four books of essays and criticism. Following his death in 2004, he was widely heralded as one of the most significant American poets to come of age in the aftermath of the Second World War.

Professional achievements, of course, occur in relation to a backdrop of personal struggles and triumphs, and it takes some type of record, whether it be a firsthand account or the recorded memories of others, to shed light on the interplay between the two.

A ‘SECOND LIFE’: In a reference to Shakespeare’s The Tempest, Hecht wrote that with his marriage to Helen D’Alessandro (above), he’d “[r]eceiv’d a second life.” Scholar Jonathan Post (opposite) points to the happy union as an important factor in Hecht’s productivity in the years that followed. (Photo: Dorothy Alexander (left); Blake Little for Rochester Review (Opposite))

A ‘SECOND LIFE’: In a reference to Shakespeare’s The Tempest, Hecht wrote that with his marriage to Helen D’Alessandro (above), he’d “[r]eceiv’d a second life.” Scholar Jonathan Post (opposite) points to the happy union as an important factor in Hecht’s productivity in the years that followed. (Photo: Dorothy Alexander (left); Blake Little for Rochester Review (Opposite))Hecht left an extraordinary written record of those struggles and triumphs, a sample of which can be seen in The Selected Letters of Anthony Hecht, edited by Jonathan Post ’76 (PhD), and released in January by Johns Hopkins University Press.

“There’s a frankness in the letters which reveals a great deal about him and his character,” says Post, “and to some degree that frankness will be a surprise to many people.”

Post is Distinguished Professor of English at UCLA and a scholar of English Renaissance as well as modern poetry. He entered the University’s graduate program in English in the fall of 1970 and met Hecht for the first time in the spring of 1972, in Hecht’s graduate seminar on William Butler Yeats and Theodore Roethke.

(Photo: Blake Little for Rochester Review)

(Photo: Blake Little for Rochester Review)“It was a wonderful exploration of poems and also a kind of whirligig of activity,” Post recalls. The course was held at the Hecht home. Helen had given birth to a son, Evan, in April, whom Post recalls as a “silent auditor in the class.” That seminar marked the beginning of what would be his lifelong friendship with the Hechts.

Months after Anthony Hecht’s death, Helen began what would prove a monumental task: recovering what would turn out to be more than 4,000 letters the late poet had written over the course of almost seven decades.

Helen Hecht recalls the germination of the project in a conversation reported to her by Anthony Hecht’s literary executor, the poet J. D. (Sandy) McClatchy. McClatchy had been talking one evening with fellow poets John Hollander and Richard Howard. “They said what a great letter writer Tony was, and the letters should all be collected.”

A happenstance phone conversation led to Post becoming the editor who would, with Helen’s input, whittle those few thousand letters, many of which are now part of the Anthony Hecht archive at Emory University, to the several hundred that appear in the book.

The letters begin in 1935, when a young Hecht was writing home from summer camp, and end in the summer of 2004, just months before he died. They chronicle nearly every major phase in between—his discovery of poetry as a student at Bard College, his service during the Second World War, his troubled first marriage, and his joyful second marriage, to Helen D’Alessandro, in 1971.

Post anticipates that scholars and other readers and writers of poetry will be interested in Hecht’s correspondence with a host of other luminaries, including Howard, Hollander, and McClatchy, as well as Richard Wilbur, Allen Tate, Anne Sexton, James Merrill, Elizabeth Bishop, and others.

Post finds the collection’s greatest significance, however, in the early letters.

“The later poems and the later Hecht is better known because he was something of a public figure then. But the part leading up to The Hard Hours is really revelatory. All of that is going to be seen and read for the first time. And I suspect that that will make a significant difference in terms of how people begin to think about the long and substantial career that he had as a poet.”

Hecht, born in Manhattan to privileged and cosmopolitan German-Jewish parents, had enjoyed an elite private school education, but had been, by his account, a mediocre student prior to his matriculation at Bard College in 1940. He began college with little confidence in himself academically.

EASTMAN QUAD: A member of the English department from 1967 to 1985, Hecht, who won the Pulitzer Prize shortly after arriving

at the University, served at Rochester longer than at any other institution. (Photo: University Libraries/Department of Rare Books, Special Collections, and Preservation)

EASTMAN QUAD: A member of the English department from 1967 to 1985, Hecht, who won the Pulitzer Prize shortly after arriving

at the University, served at Rochester longer than at any other institution. (Photo: University Libraries/Department of Rare Books, Special Collections, and Preservation)“At first I felt quite self-conscious; I thought everyone was laughing at me behind my back,” he wrote to his parents in September of his freshman year. Within a couple of years, he had developed substantially as a student and discovered his love for poetry—as well as the challenges of writing it.

“My poetry is coming slowly,” he wrote to his parents in the spring of 1943. “Producing it, even in small quantities has always been for me a painful and laborious process. (I mean painful here not in the sense of unpleasant to do, but only difficult in the extreme.) I have picked a particularly hard job for myself in deciding to write a sestina.”

McClatchy says the letters not only offer “a fuller portrait” of Hecht himself, but also “reveal the personality and character of the writer, as he is writing and as he is living, experiencing what he will later transform into art.”

Among the experiences he transformed into art was his presence at the liberation of the Flossenbürg concentration camp in April 1945.

“This letter is written primarily to inform you that the war is over, and I have come through it unscathed,” he wrote to his parents the following month. “Unscathed, of course, does not mean unaffected. What I have seen and heard here, in conversations with Germans, French, Czechs, & Russians—plus personal observations combine to make a story well beyond the limits of censorship regulation. You must wait till I can tell you personally of this beautiful country, and its demented people.”

His wartime experiences were material for some of his most haunting poems, such as “ ‘More Light! More Light!’,” which he dedicated to his friends, the German philosophers Heinrich Blücher and Hannah Arendt, both of whom fled from Nazism.

Post is at work on a book about Hecht’s poetry that will encompass the poet’s entire career. “The letters shape a number of the chapters. I use the letters oftentimes as springboards,” says Post. He adds that the advantage of writing a critical book about Hecht’s work is that “I’m freer to investigate more interpretive questions in relationship to the poems and also in relation to the life as I understand it, partially through the letters.”

For her part, Helen Hecht is struck most by the consistency and uniqueness of the voice in the letters.

“It was like having him in the room,” she says, recalling the first time she read through the letters, one by one. “The voice in the letters was so distinctive and clear and characteristically his own. I would have recognized it anywhere.”