In Review

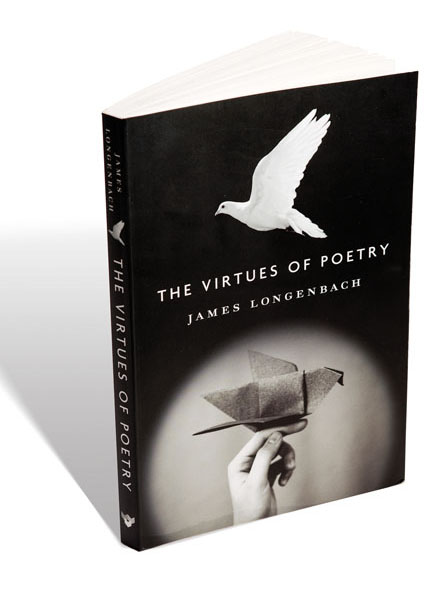

POETIC POWER: Longenbach considers the powers of poetic language. (Photo: Adam Fenster)

POETIC POWER: Longenbach considers the powers of poetic language. (Photo: Adam Fenster)“The best poems ever written constitute our future,” writes James Longenbach, the Joseph Henry Gilmore Professor of English, in opening his new book, The Virtues of Poetry (Graywolf Press, 2013). “They refine our notions of excellence by continuing to elude them.” In interlaced chapters, Longenbach considers the almost magical powers, or virtues, that poems can enact through the most ordinary means: among them, compression, dilation, intimacy, and otherness. He leads readers, with attention to the smallest inflections of language, through works by such poets as Shakespeare, Yeats, Dickinson, Marvell, Whitman, Blake, and Ashbery, and finds within them examples of the endlessly diverse powers of language.

What prompted you to write the book?

A contradiction. I found that when I was thinking about one particular poem, I would be talking about what made it interesting, worthy of attention, and so on; but then I’d be thinking about a different poem, and I’d realize that I would be talking about qualities that were inimical to the qualities that made the other poem interesting. This conflict seemed important and true to me: that you can’t legislate quality, or more perniciously, greatness—that the very quality that makes one poem fascinating and gripping and lasting might be the very thing that ruins another poem. The conflict became the book’s framing notion. It was hard to figure out a structure for the book that would be true to the conflict, for how do you turn this notion of not being able to have a generalizable recipe for excellence into an argument that doesn’t itself seem like a recipe?

You’re both a literary critic and a poet. How did those roles influence the book?

All poets of any worth are superb critics. They may not necessarily write their criticism down formally, but you have to have read a thousand poems carefully in order to write just one, and you have to have investigated them and felt yourself being fascinated by how their language works. So I don’t feel different from any other poet. Some poets write a lot of criticism and some don’t, but I don’t think their minds work differently. I also think—and this is something I press upon my students—the writing of good prose sentences is a rigor that any poet benefits from, not because of what you’re writing about, but because you’re making shapely sentences into shapely paragraphs. This is something that fuels the writing of poetry.

You write about “excellence” as something that takes many forms in poetry. What do you mean by excellence?

It’s not a word I’m really happy with, and it occurs mostly in the preface, when I was forced by the occasion of making a coherent book to write a very pithy account of what the book does. I’m much happier with the more elusive and mysterious word “virtue,” which carries the connotation of something magical—though I don’t mean to speak about magic. I mean to talk about qualities of language in poems that we can discuss in rational ways. The impetus behind a poem might be very mysterious and strange, but the act of writing a poem is a very knowable, rational process: shaping the raw material of a language into a set of patterns. I hope it’s clear I was at pains to say you can’t ever really know what excellence is going to be, and that every example of excellence you may have accumulated will not ensure that any of those modes of excellence will succeed in the next poem. Neither will they prevent the next poem from exhibiting a kind of charisma that is unprecedented in your experience of poetry.

In these essays, you give significant attention to the process of reading poems.

Because I’m at pains to get my students to read the language of a poem very closely, I say to them—and I mean this as a challenge; it’s not absolutely true, but it’s almost true—that if we talked about a poem long enough, it would be impossible for us to disagree about it: we would have described the language so carefully, so specifically, that we wouldn’t have anything to argue about. That’s not utterly true, but it’s amazing how true it is. You teach Hamlet year after year after year, and what’s remarkable is not that people think different things about it—what’s far more remarkable is that by and large everybody thinks the same things about it. The pressure the object exerts on you is far more mysterious than the fact that we have varying responses to the object. And it’s harder to describe.

Who’s the reader you’re addressing in this book? Are you writing for people who’d like to be poets?

In a sense, you could say that the book is written for people who want to write poems; however, that’s a subset of people who want to read poems. The act of writing and the act of reading are almost impossible to separate from each other, and you simply cannot be a writer without being a voraciously scrupulous reader. Throughout the book, I’m speaking to someone who wants to write only inasmuch as I mean to be speaking to someone who really, really loves—or wants to learn how it feels to love—the act of reading a poem with intensity and, therefore, pleasure. That pleasure often makes one feel creative, and maybe it will make one write a poem—or not. It almost doesn’t matter.

You mention in the book that Andrew Marvell’s poem “The Garden” is a special one for you, that “everything I love about poetry is epitomized by this poem. It is as if the poem were a house I’d lived in all my life without knowing it.” What makes a particular poem especially meaningful for a particular reader?

I may be speaking productively with a forked tongue, because I always want to insist to myself, and insist to a reader, and insist to any student that one must try to be available to every kind of poem that you could possibly avail yourself of, especially the ones that you think you don’t like. Those are the ones that you have to return to, because if you don’t like a poem, that probably means there’s something wrong with you, something limited about you. Ideally, if we were the best possible readers, we would find everything inspiring. But because we are inadequate readers, we don’t like certain things. Of course there are going to be times when we don’t like something or can’t figure out how to enter it, but as much as possible, you want to try to keep that thing on the table. The fact that you don’t like it ought to keep bugging you—especially if somebody else who’s smart and interesting does like it. So given this goal of radical openness, then inevitably there are going to be some works of art that for some reason appeal to you more deeply, more intrinsically. It’s hard to say why. Perhaps even more mysterious and more wonderful is when one feels one’s deepest inclinations changing, when a poem—or an anything—that one has not found inspiring for years suddenly rears up its head, and you say, “Oh, my God. I require this. Where has this thing been all my life?” Well, it’s been right in front of me. Where have I been all my life?

Do your students come prepared to do close reading? It doesn’t seem there’s a lot in the contemporary world to encourage that skill of careful attention.

They do come prepared to do it, and then they do it, because in my classroom they’ve got to do it. And students don’t have trouble with that. Students in my experience are attracted to difficulty. When I teach my course on James Joyce’s Ulysses, that’s generally the biggest enrollment I get, usually 60 or 70 kids, and it’s not because the course fulfills requirements or anything. I think the human brain craves difficulty. Reading poems is a very good way to improve the mind, because, especially if you’re dealing with lyric poems, you’re sitting there looking very closely at this little patterned collection of, what, 43 words? And you have a lot of time really to focus in on those words and not let yourself go somewhere else. Often—usually—in a typical hour and 15 minute class, I’ll never cover more than two or three poems. Sometimes, only one. The literary critic Richard Poirier always spoke of how he preferred the phrase “slow reading” to “close reading,” and I like that, too. I think “slow reading” seems like a better metaphor—it’s what poems demand, and it’s why people who don’t generally read them sometimes feel kind of mystified by them: poems ask for a slowness of attention that, if you’re just used to reading language as a disposable vessel for information, you’re not used to exercising. Students learn how to be unintimidated by that slowness, how to inhabit it, how to glean things from it, how to enjoy it: that’s the extremely useful, universally applicable skill that comes out of reading poems. So finally, I think it’s most important simply to learn how to like poems, how to be devoted to poems, and if I have one overriding pedagogical goal, it would be no bigger than that.

What gives a poem lasting influence?

We think of 400 or even of 50 years as being a long time. But in the history of art, that’s nothing. Most of the art that’s produced in any 100-year period is totally forgotten. And none of us will live long enough to know what art will last from the moment in which we live. We generally read, if we’re well read, maybe eight or nine poets from the 19th century, which ended only 113 years ago. And so which eight or nine are going to last from the 20th century? I can think easily of 30 that seem really, really good. That’s scary. But while only a little bit lasts, it takes a great many people to produce that little bit, and the minor figures who may be forgotten are important. They may not end up being an important part of the story, but they’re an important part of the event. It takes a lot of people being interested in the production and reception of art—or of anything—to make that little bit of lasting achievement. So in that sense we’re all really noble participants in this ongoing enterprise. It all sounds so high-minded, doesn’t it?