Features

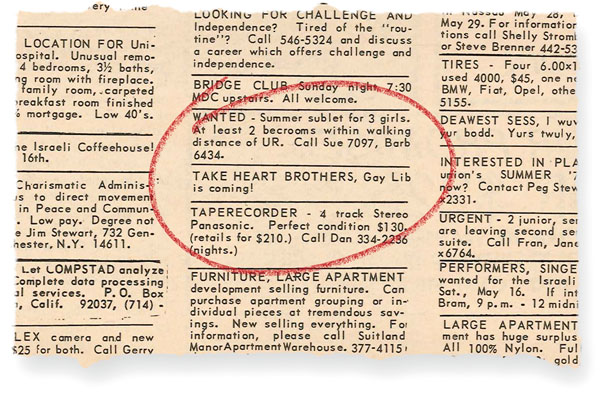

(DE)CLASSIFIED: “I was fired up,” says Larry Fine ’72, after coming out as gay at the end of his sophomore year. He submitted this classified ad, which appeared in the Campus Times on Friday, May 8, 1970. (Photo: University Libraries/Department of Rare Books, Special Collections, and Preservation )

(DE)CLASSIFIED: “I was fired up,” says Larry Fine ’72, after coming out as gay at the end of his sophomore year. He submitted this classified ad, which appeared in the Campus Times on Friday, May 8, 1970. (Photo: University Libraries/Department of Rare Books, Special Collections, and Preservation )In the final days of the spring semester of 1970, sophomore Larry Fine ’72 placed a few coins in an envelope, along with a note, and dropped the envelope into a slot on the office door of the Campus Times.

The note, seven words long, appeared in the classifieds the following week: “TAKE HEART BROTHERS, Gay Lib is coming!”

It was the year after the Stonewall riots, which had begun on a night in June 1969, at a popular gay bar in New York City’s Greenwich Village, when patrons, long the target of police round-ups, decided to resist. The protest was a call to action, and within months, an organized gay rights movement was emerging nationally.

Much of the activity would take place on campuses. As Fine placed his cryptic note in the Campus Times, a graduate student in physics, Bob Osborn ’74 (PhD), was also planning to bring the gay liberation movement to Rochester.

A southerner, Osborn had worked across the Deep South as a white ally in support of the African-American freedom struggle. He brought his experience in political organizing to Rochester where, in the fall of 1970, he laid the groundwork for a meeting in Todd Union on Saturday evening, October 3, that would officially launch the University of Rochester's chapter of the Gay Liberation Front. Rochester would become the third campus in New York state, after Columbia and Cornell, to open a chapter of the national organization.

In the next several months, Osborn, Fine, and a small, committed core of students from the River Campus and the Eastman School successfully petitioned Student Activities for official recognition; established an office in Todd Union; set up a small library of books and other resources related to gay issues; created a speakers bureau, in which members offered themselves as educational ambassadors, speaking before classes and local organizations; and with the help of a typewriter, a mimeograph machine, and a hand stapler, created a newsletter called the Empty Closet.

By spring 1973, the group, known by then as GLF, would spawn a series of organizations in the community—the Gay Brotherhood, Gay Revolution of Women (later the Lesbian Resource Center), and others—which would unite under the umbrella of the Gay Alliance of the Genesee Valley.

Today’s Focus: Gender Identity

Since the Gay Liberation Front began on the River Campus in 1970, the University has maintained a student group dedicated to the interests and concerns of gays and lesbians. As the movement has progressed, students have followed in casting an even broader tent, embracing those who identify themselves as bisexual or transgender as well.

Today, the LGBT student group is called the Pride Network. Clint Cantwell ’15, a rising junior from Palmyra, N.Y., who is the group’s vice president and social chair, says that as of the end of the 2012–13 academic year, the network had just over 300 members, and about 20 whom he calls “active members.”

“For lesbians, gays, and bisexuals, a lot has happened in terms of rights and acceptance,” says Cantwell. While the GLF struggled in the 1970s to encourage gays and lesbians to come out of the closet and join the organization, the Pride Network has attracted a considerably larger population of LGBT students as well as plenty of straight allies.

And while the GLF had always counted a few quiet allies among faculty and administrators, today there are people in virtually every segment of the University who are openly part of the LGBT community.

But there’s some substantial work left to do, Cantwell says. “Transgender people are the biggest issue right now.”

They’re a small minority of the community. Cantwell, who identifies as gay, estimates that there are about 10 to 15 openly transgender students on campus, two or three of whom are active members of the group. But they’re the people who face the greatest difficulties and the most misunderstanding among their peers.

“It’s very difficult to get gender-neutral bathrooms,” he says, underscoring how something as simple as using a public restroom can be stressful and complicated for people who are transgender. Cantwell notes that the network helped bring about a gender-neutral bathroom outside Starbucks in Wilson Commons.

This fall, the group plans a series of events to help educate the community about the fluidity of gender identity and the variety of ways in which it’s expressed.

—Karen McCallyThis year, as the alliance celebrates its 40th birthday, it’s in the midst of a documentary project tracing its history and the history of the gay and lesbian community in Rochester and western New York. The project, called Shoulders to Stand On, has received funding from the New York State Archives as well as the Arts and Cultural Council of Greater Rochester.

More than 40 years after its inaugural issue, the Empty Closet is still in print, published by the alliance since the summer of 1973. It’s the oldest continuously published gay newspaper in New York and the second oldest in the nation after the Washington Blade, which moved to an all-digital format last year.

As part of the project, the Rush Rhees Library Department of Rare Books, Special Collections, and Preservation worked with the alliance to digitize the paper. Since last fall, well over 400 issues have been made available on a searchable online archive.

OUT AND ONLINE: More than 400 past issues of the Empty Closet are available online at www.lib.rochester.edu/?page=emptycloset. (Photo: University Libraries/Department of Rare Books, Special Collections, and Preservation )

OUT AND ONLINE: More than 400 past issues of the Empty Closet are available online at www.lib.rochester.edu/?page=emptycloset. (Photo: University Libraries/Department of Rare Books, Special Collections, and Preservation )“The Empty Closet has been, and is, the primary source of LGBT history in Rochester,” says Evelyn Bailey, using the acronym for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender. Bailey, a long-time member of the alliance and the executive producer of the project, says that in the past several years, volunteers from the alliance have used the paper to identify and locate almost 100 people interviewed for the next phase of the project, a documentary film titled Shoulders to Stand On. The film will premiere in Rochester this fall as part of the annual Image Out gay and lesbian film festival.

Bailey calls the students who forged the University’s GLF “pioneers.”

“The fear that went along with being gay in those early days was extremely crippling,” she says.

And not only for gays and lesbians, but also for the larger community.

Bailey says that the GLF’s pioneers forged a culture of openness toward gays and lesbians that brought benefits to the region. Before their work began, the environment “did not allow people to be who they were and to express their talents, be able to impact their workplace or the political or economic arena to the degree that they do today.” Bailey notes that by a variety of indices, the Rochester metropolitan area ranks in the top 20 “most gay-friendly” cities in the nation.

There are many reasons for Rochester’s status—its high proportion of college graduates and major employers that have long had a financial interest in gay-friendly employment practices, for example. But no degree of friendliness would be measurable unless someone, or some group, at one point began to challenge traditional norms.

Larry Fine says he’s used to being interviewed, though not about gay issues.

“I’m used to being asked about pianos,” he says from his home office in Palm Springs, Calif.

For the past 35 years, Fine has been a piano technician and publisher of The Piano Book, a nearly 250-page guide to purchasing and maintaining pianos. But when asked about his work with the Gay Liberation Front, he pours forth with the story of his personal awakening in the spring of 1970.

He’d been participating that semester in a psychology experiment in which he played the part of patient as the professor, graduate student in tow, led Fine through a series of counseling sessions. The scenario, by itself, was not unusual—“it often happened when you were a sophomore, you got recruited into experiments,” he recalls—but for Fine, the experiment would have far-reaching effects. As the sessions wore on and the semester drew to a close, the professor asked him about one subject that had yet to come up in all the 20-year-old young man’s hours of personal revelations: sex.

“I told him, ‘I think I’m a homosexual.’ He had me say it again and again to get used to it. And he said, ‘You need to meet other gay people.’ ”

Days later, Fine met a gay senior named Jeff, who would change Fine’s life through a long conversation on a River Campus lawn. “All of a sudden I realized I was part of a larger world,” Fine says. Aside from a chance encounter or two in the weeks leading up to graduation, Fine never saw Jeff again after that day. But the conversation left a profound impression on Fine. “I was fired up,” he says. He placed the fortuitous note in the Campus Times. And in August, he strapped a pack on his back, and hitchhiked to San Francisco in search of the gay liberation movement.

It’s not surprising that young people like Fine could go about their daily lives unaware that there was a gay community in their midst.

“The community at that time was cliquish,” says Bailey. “You would have certain known gay men or gay women who had a circle of friends. They would gather fairly often for dinner parties, and they would invite people whom they knew would not out them.”

During his journey to the San Francisco Bay Area, Fine encountered a similar code of discretion. Verbal tips, handwritten notes, and pay telephone calls led him eventually to an abandoned warehouse.

“You had to knock a certain way, or say a certain thing when they answered the door so they knew you were OK,” Fine recalls. “Inside were young gay people who were involved in the GLF, and I found out from them other places to go.”

He spent a week in Berkeley, staying at a GLF crash pad for gay visitors and attending gay coffeehouses and other events. “I met a guy named Michael, who became my boyfriend for the next few months and who came back to Rochester with me—believe it or not.”

The Rochester GLF began with a simple announcement in a late September issue of the Campus Times: “UR Gay Liberation Front will hold an interest meeting. . . Open to all people who believe that realization of basic civil rights for all minority groups must come from organized effort.”

“It was Bob Osborn who started the group, not me,” says Fine. Osborn, who died in 2004, was the author of that announcement and organized and moderated the first several meetings of the group, which featured guest speakers and discussions on topics such as Military Service and the Homosexual, Homosexuals and the Law, Women’s Liberation, and Dialogue with the Church.

In those meetings and through the Empty Closet, Osborn, inspired by his activism in the South, would work to cast gay liberation as a natural outgrowth of the African-American civil rights movement.

He’d sat in the U.S. Senate gallery during the passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act. Friends recall that he had marched from Selma, Ala., to Montgomery in the 1965 demonstration led by Martin Luther King Jr. to secure voting rights for African Americans who’d long been harassed and intimidated at the polls.

“For him, this was a continuation of the civil rights movement, and he spoke in those terms,” says Fine, who became fast friends with Osborn after the first GLF meeting.

In his mid-20s, Osborn was older and more overtly political than most of the group’s student members. Several students in the group, especially those coming to campus as freshmen undergraduates, were not even sure of their sexual identity, let alone how they believed it should be expressed in social and civic life.

Gary Clinton ’73 still remembers, word for word, the note that he read in the Campus Times at the end of his freshman year.

“It said, ‘Take heart, brothers. Gay lib is coming.’ I remember thinking, ‘This might be interesting.’ ”

EDUCATOR: Hagberg, a Suzuki piano instructor, spearheaded the speakers bureau, an educational tool founded at a time when many people “never had the opportunity to talk to gay people before.” (Photo: Adam Fenster)

EDUCATOR: Hagberg, a Suzuki piano instructor, spearheaded the speakers bureau, an educational tool founded at a time when many people “never had the opportunity to talk to gay people before.” (Photo: Adam Fenster)That summer, at home on Long Island, Clinton continued to mull over that message. “I wasn’t sure what my sexuality was,” he says of himself as an 18-year-old freshman. “I knew I liked men. But I wasn’t sure what that meant in those days.”

When the GLF started in the fall, he was slow to take part. “I wasn’t much of a joiner then,” says Clinton, now the dean of students at the University of Pennsylvania’s law school.

Karen Hagberg ’76E (PhD), then a graduate student in musicology at the Eastman School, says, “I knew I was gay, somehow. But I’d never heard of anybody else who was. I mean, we really used to all think that we were the only ones in the world, no joke.”

Hagberg had come out to a few friends, such as Robert (R. J.) Alcala ’71E, an undergraduate studying oboe at the Eastman School, who was also gay. But she’d never publicly identified herself as gay. “It was exciting and scary to actually go into a room that was designated for a group of gay people,” she recalls of her first GLF meeting.

Like Hagberg, Patti Evans ’73 came out first to a couple of friends and had little familiarity with gay life in Rochester. When she approached a Todd music room on October 3, 1970, it was her second attempt to walk into an on-campus meeting of gay students.

“There was a planning meeting before that one,” she says. “It was up on the Hill, which was my dormitory. I hadn’t come out on campus. I was kind of nervous.” Intent on going, she approached the lounge where the meeting was to be held. She saw just three people. “There was a very flamboyant man,” she recalls, and two women seated close together. She kept on walking.

It was easier for Evans to approach the October meeting with confidence. “There were, like, 40 people at that meeting,” she says (The Campus Times would report an attendance of “approximately 100,” in its Dec. 13, 1970, issue). From that day forward, she became part of the small group of activists who shepherded the GLF through its early years.

She helped plan the group’s first dance, and more than 40 years later, she remembers vividly “the feeling I had at that dance.”

It inspired her to write a letter about it in the Campus Times as well as in the Empty Closet. In both places, she signed her name “Patricia Evers.”

Today she laughs about that decision. “It was kind of naive of me to think I could get away with that. It wasn’t that big of a campus.”

Though she concedes now that the robust attendance at the dance may well have been due to other factors than a chance to experience freedom from proscribed social norms—“we had a live band and free beer”—the experience was indicative of the reaction she says she continued to feel around campus. She feared disapproval. She didn’t get it. “I guess I was surprised. I guess I didn’t fit a stereotype.”

Hagberg, too, remained active in the GLF from that first meeting forward. She established the speakers bureau, in which members of the group would volunteer to appear before classes at the University, and at schools and other local organizations to talk about homosexuality, what it meant to be gay or lesbian, and the nature of the discrimination they faced and sought to eradicate.

“Some of us thought that if everybody would just come out, we wouldn’t have a problem,” says Hagberg. “And that was the impetus for forming the speakers bureau.”

GLF speakers appeared in several psychology classes. Hagberg recalls appearing before psychology professor Vincent Knowlis’s Sex and Gender Roles class toward the end of the fall 1970 semester. Knowlis held the class in his home. “I'm not sure why,” she says. “I’m not sure if he didn’t feel comfortable having it in his classroom.” Regardless, Hagberg says the experience was “really amazing, because people never had the opportunity to talk to gay people before.”

“There was certainly no backlash,” Fine recalls of the early days of the group. “I don’t know what people were talking about among themselves, but there wasn’t a lot of reaction. I think for the most part, people weren’t paying attention.”

The Campus Times, however, was giving prominent coverage to the GLF by the fall of 1971. A news article in October reported on the group’s upcoming one-year anniversary celebration, a series of events including a concert, dance, coffeehouse, and teach-in. Noting that “everyone is welcome,” the Campus Times reported, “Since last October, when Gay Liberation was still an uptight topic on campus, GLF has held four public dances at the university. Nobody knew, at first, exactly who would attend these supposedly far-out functions, but when the first dance was over, it was clear that people here are less hung-up than they might seem, or at least less hung-up than GLF members feared they would be.”

In December, the Campus Times ran a front-page feature on the group in which reporter Marc Rosenwasser ’74 cited GLF’s claims about deeply ingrained societal homophobia and its members’ political activities in response. The Rochester police had recently raided two popular gay bars, arresting three patrons as well as the owners of the bars—the patrons for loitering and the owners for “failing to display a license for dancing.” “Osborn charges that the raids were illegal and stated that countersuits were being filed along the grounds of false arrest,” Rosenwasser reported.

Meanwhile, the Empty Closet was fast becoming an effective tool for community building, both within and outside the University.

“When it first began at the University of Rochester, it was the means of communicating among university students and the greater Rochester community,” says Bailey. “As far as news about what was going on, it was the conduit.”

Osborn, Fine, Evans, a freshman named Marshall Goldman ’74, and others distributed the paper at Rochester’s gay and lesbian bars.

Its readership was—and is, Bailey stresses—much larger than the openly gay community.

“I think the paper represented the touchstone between the LGBT community that was closeted, and not closeted.” She tells about a man she met recently who reads the Empty Closet “every single month, cover to cover, front page, back page,” but won’t pick it up at a newsstand. “He’s gay. He’s not out. He won’t pick it up outside because he doesn’t want to be seen, identified with it. That’s his major source of information and connection to the community and to the people in the community. That has always been part of the real value of the Empty Closet.”

The first issues of the paper combined national and local news about the gay rights movement with listings of upcoming GLF events, poetry, short prose, opinion pieces, the “GLF Bookshelf,” and an advice column called “Dear Gale Gay.”

The paper also compiled a written record of harassment and discrimination in the city as well as on campus.

“I have made my activities in GLF and the fact that I am gay known to the denizens of my dorm, and got generally good to indifferent reactions,” wrote Goldman in the spring of 1971. But one day, he alleged, some residents trapped him and a male friend in Goldman’s dorm room by stuffing pennies in the lock, which the head resident came and removed. Later, freed from his room, Goldman lost his eyeglasses. He found them later in a Hoeing lounge, with an obscene rhyme attached that made reference to his homosexuality.

The “comment,” as Goldman called it, and those like it “won’t stop us from being ourselves and won’t push us back in our closets.”

In June of the same year, the paper reported allegations that the Eastman School dean of students was using her office to intimidate and penalize gay students. “This has resulted in a virtual reign of terror at the Eastman School, where gay students are extremely fearful of being open about themselves,” the report noted.

Inevitably, though, gay students would form relationships, and in some cases, live openly as couples. In his suite in Anderson Hall, for example, Fine shared his room with Michael. The room was a double, and Michael had moved in when Fine’s roommate didn’t return for the fall semester.

“At some point, I had to tell my suitemates who this guy was,” Fine says. “They were very, very good about it. One of the guys was actually on the sex education committee for the student government. The others were curious. And who knew? I took a chance. It was scary when I first broached the subject.”

By his senior year, Clinton would meet a freshman, Don Millinger ’76, who would become his life’s partner. The couple married in October 2011 in New York City, 39 years, virtually to the day, after they met.

They lived openly as a couple on the River Campus during the 1972–73 academic year. “By the end of my first semester, I basically moved myself into Gary’s dorm room in Helen Wood Hall from the Hill,” Millinger says.

While Clinton had been initially reticent about taking part in GLF activities, Millinger jumped right in. In his second semester at Rochester, he began participating in the speakers bureau, standing before his classmates in psychology classes, serving as “a real-live, honest-to-God, three-dimensional homosexual,” he says. “Things got around. People knew I was gay.”

MARRIED? “When I’m at work, I’m married; when I come home, I’m single,” says Millinger (left, above and opposite), who works in Manhattan and lives in Philadelphia with Clinton. The two met at Rochester in 1972 and married in 2011 in New York, which recognizes same-sex marriages. (Photo: Michael Perez/AP Images for Rochester Review)

MARRIED? “When I’m at work, I’m married; when I come home, I’m single,” says Millinger (left, above and opposite), who works in Manhattan and lives in Philadelphia with Clinton. The two met at Rochester in 1972 and married in 2011 in New York, which recognizes same-sex marriages. (Photo: Michael Perez/AP Images for Rochester Review)“And then he was elected treasurer of the student government,” says Clinton.

As a national organization with chapters throughout the country, GLF was always intended to be a community-based group. University students, however, were prominent among the leaders in many communities, not least Rochester.

In December 1971, Osborn told the Campus Times that the group had a “floating membership” of about 200 people, out of whom 12 were University of Rochester students.

According to the recollections of Evans, Fine, and others whom alliance volunteers interviewed for the Shoulders to Stand On project, Student Activities grew concerned about whether the group could genuinely be considered a student organization.

Today, members disagree about whether the students in the GLF were singled out unfairly by Student Activities.

“It wasn’t a hostile thing,” says Evans. “It was a legitimate concern that they had. It was using activities funds and serving only a handful of students.”

Fine disagrees, calling the concern expressed by Student Activities “a red herring.” He recalls appearing before a student appropriations committee to argue the group’s case.

“I said, ‘Look. There’s a foreign film festival and most of the people coming to it are from the city. You’re giving money to this festival, so you really have no basis for complaint here.’ ”

Fine says the GLF prevailed. But by the spring of 1973, GLF members voted to form two autonomous organizations: an all-student University of Rochester GLF, led by undergraduate officers, located on the River Campus, and retaining recognition and funding from Student Activities; and an organization for people in the greater Rochester community.

“Through the assistance of the University and student body,” the Empty Closet reported, the group has grown “to the point that [non-students] are now able to leave the campus, and move into town. It is anticipated that both students and townspeople will find expanded participation because of more convenient locations and a more comfortable peer relationship.”

The group’s membership and financial resources would shrink drastically. But Clinton and Millinger, both of whom were among the individual signers of a letter from the GLF to the Campus Times announcing the April 1973 “emergency meeting” to discuss the future of the group, say that in retrospect, the reorganization may have been a good deal for students, particularly undergraduates like themselves.

“I went to a few meetings at the beginning, and I remember thinking, ‘Who are these people?’,” Clinton says. “They were older—which meant they might have been anything between 25 and 40—and I was used to student groups.”

“There were two separate kinds of priorities,” says Millinger. “Bob and the folks from town were looking at the social change aspect. On campus, students were figuring out, ‘I’m 19, 20 years old, I think I’m gay, I am gay, I may be gay, but what does that mean to me, and what does that mean on campus, and how secure can I be, and who can I talk to—all those kinds of things.” The reorganization of GLF into an all-student group, Millinger says, was “a good motivator to actually have a more significant student presence on campus.”

For the next several years, that goal proved elusive in practice. The GLF would never count more than a dozen members. Jay Stratton ’74 (MA), a graduate student in linguistics, kept a diary in which he chronicled the activities of the GLF through his eyes as a participant-observer. He donated a typed version of the diary to Rush Rhees Library last year.

From 1974 to 1980, he recorded car rides from the River Campus to the Gay Alliance meetings, a “gay table” in the dining hall, petition drives that proved disappointing, and dances that were sparsely attended.

The dances attracted spectators, according to Stratton, who eventually overwhelmed the dance floor. “It was rather funny in that most of the gay people had already left and they were gawking at others of their own kind,” he wrote.

But the group sustained itself as one among many student organizations. And the groups they spawned in the greater Rochester community sustained themselves too, with the help of tools and leaders shaped and developed in the GLF’s first years as a student organization.

Evans remained active in the alliance, advocating legal equality, and eventually becoming elected chairperson of the New York State Lesbian and Gay Lobby.

Hagberg participated increasingly in lesbian feminist activism, raising awareness of violence against women and of the ways in which sexism had infused the gay movement.

Evans, Hagberg, and Alcala went frequently on the local airwaves as part of the speakers bureau. And the bureau, Hagberg says, remains a key part of the work of the alliance today.

“We were making it up as we went along,” Fine says.

Occasionally, he’ll look back and find some of his writings “childish.”

“I can be quite critical. I was 21 years old. I’m 62 now.” But he’s also astonished at what they accomplished, and the meaning it had for people who looked at the pioneers with silent admiration.

“A lot of the effect of what we did was not measurable at the time,” says Fine.

He tells about a gathering he attended years after he’d left Rochester. “I encountered friends from my college days who, unbeknownst to me, had been struggling with their sexual orientation at the time, but who were not ready to come out. I was a hero to them. I was greeted as a hero.

And I was astounded. I had no idea.”