Features

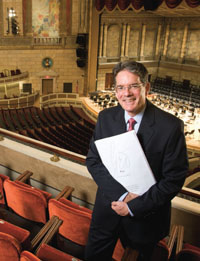

A COMPLETED VISION: The Eastman School’s East Wing (below), which George Eastman had envisioned, was completed under Lowry’s tenure, as was the renovated Kodak Hall at Eastman Theatre. Lowry’s composition Geo commemorated the hall’s opening. (Photo: Kurt Brownell)

A COMPLETED VISION: The Eastman School’s East Wing (below), which George Eastman had envisioned, was completed under Lowry’s tenure, as was the renovated Kodak Hall at Eastman Theatre. Lowry’s composition Geo commemorated the hall’s opening. (Photo: Kurt Brownell)In the hours following the official announcement that Douglas Lowry, the Joan and Martin Messinger Dean Emeritus of the Eastman School, had died, a crowd gathered.

The site was Eastman’s Main Hall, the wide corridor with the prosaic name that from that day forward would be known as Lowry Hall.

By the time Jamal Rossi took to a podium, the gathering had extended from the easternmost staircase to the western entranceway. Named dean upon Lowry’s resignation just nine days before, Rossi, Eastman’s longtime professor of woodwinds and, as executive associate dean, Lowry’s closest associate at the school, remarked on the gathering and its meaning:

“This—this alone—right here, this view. What a remarkable tribute to a remarkable person.”

(Photo: Adam Fenster)

(Photo: Adam Fenster)Lowry was named dean of the Eastman School in 2007. He came amidst a transition in which the school was making major investments in facilities and seeking greater visibility in a rapidly changing environment in which no music school, no matter how distinguished, could take an illustrious position for granted.

In the spring of 2011, University Trustee Martin Messinger ’49E and his wife, Joan, decided to endow the Eastman deanship, underscoring not only their commitment to the school, but their confidence in Lowry’s leadership.

That September—the same month in which he was officially installed as the Joan and Martin Messinger Dean—Lowry was diagnosed with multiple myeloma.

PARTNER: “This is hallowed ground, and we’re happy we could have been part of your lives,” Marcia Lowry told the gathering in the newly named Lowry Hall. (Photo: Adam Fenster)

PARTNER: “This is hallowed ground, and we’re happy we could have been part of your lives,” Marcia Lowry told the gathering in the newly named Lowry Hall. (Photo: Adam Fenster)He worked through his illness and treatments. As dean, he endured a heavy travel schedule, as he sought to build relationships around the country and globe. As a composer, he continued to create music.

His six years at Eastman were jam-packed with accomplishments in both of those roles.

The renovation of Eastman Theatre to become Kodak Hall at Eastman Theatre was completed under his leadership. His composition, Geo, was commissioned by the Rochester Philharmonic Orchestra to celebrate the opening of Kodak Hall in October 2009.

Jeff Beal ’85E, an Emmy Award–winning composer for film and television, praised Geo, a five-part, motion-filled, cinematic musical journey Lowry said was inspired by George Eastman’s role in developing the motion picture, and by the Eastman Theatre’s early history as a movie house. “Geo has a classicism that’s very literate, but also a joy to it that isn’t trivial,” says Beal. “Celebratory pieces are looked at as banal. But Geo is just a really genuine, joyful, classy tribute.”

Lowry oversaw the construction of Eastman’s East Wing, a part of the school originally envisioned by George Eastman that includes Hatch Recital Hall and other up-to-date performance, rehearsal, and teaching spaces.

Last February, the Rochester Philharmonic premiered another of Lowry’s compositions that celebrated the Rochester region’s distinguished past: The Freedom Zephyr, a tribute to the Underground Railroad that combined music with texts by Frederick Douglass, Walt Whitman, and Ralph Waldo Emerson.

Select Compositions

The Freedom Zephyr (2013). A celebration of the Underground Railroad. Rochester Philharmonic Orchestra, with narrator Paul Burgett ’68E, ’76E (PhD) and guest conductor Ward Stare.

- Wind Religion (2013). To commemorate the 60th birthday of the Eastman Wind Ensemble.

- Geo (2009). To commemorate the opening of Kodak Hall at Eastman Theatre. Rochester Philharmonic Orchestra, Christopher Seaman, director.

- Good to Go (2008). Trio for oboe, horn, and piano. Premiered at the International Horn Society Convention, Denver, Colo.

- Between Blues and Hard Places (2007). Cincinnati College-Conservatory of Music Chamber Players.

- Exordium Nobile (2003). Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra, Paavo Järvi, director.

- Blue Mazda (2003). Monodrama for soprano, brass, piano, and percussion. Piece a’ Brevis (2003). For four trumpets. Recorded on New Dimensions (Summit Records) by the Freiburg Trumpet Ensemble.

- Suburban Measures (1993). For trumpet and organ. Recorded on 20th Century Music for Trumpet and Organ (BIS) by Anthony Plog (trumpet) and Hans-Ola Ericsson (organ).

These were only his most tangible accomplishments. Alone, they constitute “an amazing legacy,” says Rossi. But, he adds, “I’m not sure that’s what his greatest impact was.”

“As musicians, we talk all the time about what separates a great performance, somebody who plays beautifully, with great sound and amazing technique, from a real artist,” says Rossi. “For Doug, the ability to connect with people was his artistry.”

The ability to connect and communicate—no small matter in any leadership role—is especially important in stewarding an evolving institution that has so much history behind it.

“We deal, in a way, with the past. We don’t discard things from the 17th century because we’re now in the 21st,” says Vincent Lenti ’60E, ’62E (MA), professor of piano and historian of the Eastman School who has taught at the school for more than 50 years.

And yet, he notes, as tastes, demographics, and modes of creation and distribution of music evolve, schools must respond. The result has been division over the very mission of music schools. Is the job of faculty at a school like Eastman to train fine musicians? Or should Eastman faculty also focus on helping students create ways to make a living through their art?

“There are people who say it’s not my job as a teacher to get students jobs. My job is just to teach them,” says Lenti. “But we wouldn’t survive very long if we kept turning out a lot of wonderful people who couldn’t get employed.” When necessary, he says, Lowry “had a way of coaxing people” to understand that their roles as mentors had broadened.

Lowry was among the arts leaders who recognized that helping students prepare for jobs meant reimagining ways of connecting with audiences. Among his projects was the Paul R. Judy Center for Applied Research, launched this past summer. The center, responding to the declining audiences for major American orchestras, aims to promote research into and experimentation with alternative models for ensembles.

TRIBUTE: Following the announcement of Lowry’s death on October 2, students, staff, and faculty convened in Eastman’s Main Hall, renamed Lowry Hall.

TRIBUTE: Following the announcement of Lowry’s death on October 2, students, staff, and faculty convened in Eastman’s Main Hall, renamed Lowry Hall.  “[Lowry’s] talents complemented each other,” says composer Jeff Beal ’85E of Lowry’s skills as an administrator, composer, and conductor. “He could see a puzzle and know how to organize it, know what’s important and what isn’t. (Photo: Adam Fenster)

“[Lowry’s] talents complemented each other,” says composer Jeff Beal ’85E of Lowry’s skills as an administrator, composer, and conductor. “He could see a puzzle and know how to organize it, know what’s important and what isn’t. (Photo: Adam Fenster)His quest to spur innovation, however, didn’t preclude active support of traditional models. Christopher Seaman, conductor laureate of the Rochester Philharmonic, says, “From the standpoint of the Rochester Philharmonic Orchestra and myself as its former director, Doug was the perfect dean of the Eastman School. He loved the orchestra, he understood its excellence, and everything he did for us was aimed at the benefit of both organizations and their symbiotic relationship.”

In His Own Words

“In the coming years, Eastman will take a hard look at the breathtaking changes in the way that music is experienced and consumed, and examine the emerging relationship between music and other art forms, particularly new media. We need to lead this exploration, define its path of events, revive live music.”

—Quoted in Eastman Notes, Summer 2007

“The notion of vigorously connecting your music with other art forms is not a new idea. Stravinsky’s association with Diaghilev brought us Petrushka, Firebird, and Le Sacre du Printemps. . . . This spirit of collaboration will be central to the survival and splendor of music’s next great era, as music tumbles about in the combustion chamber of the real world, the robust theater of ideas; not just musical ideas inspired by somebody else’s musical ideas, but the mosh pit of literature, visual art, drama; of the sciences, of social friction, of politics; in short, the mosh pit of the human condition—the human condition with which you must and will engage. Trust me, it needs you.”

—Eastman Commencement Address, May 2008

“Just a few short months ago, we sent that next generation of musical leaders out in the world. Our guest was Clive Gillinson, the executive and artistic director of Carnegie Hall. Clive began his speech rather inauspiciously, at least from my perspective. He declared to this sea of graduates something along these lines: ‘In 20 years, 90 percent of you will be doing something different than what you originally planned.’ Understand that the house was packed to the rafters with the parents and families of graduates. I remember thinking, ‘Clive had better be good on the rebound.’ Which he was, of course. His provocative message really wasn’t that our Eastman graduates would abandon their dreams. His point was that those very core musical dreams may likely take on a different form at some point.”

—Convocation Address, September 2010

“Music has always been a public art, with some part of it, I guess, held in private reserve. But one of my fears is that that private reserve has gotten larger and larger, and the public stake has gotten smaller and smaller. Maybe because we spend so much time indoors, we become very gifted at wrapping up our music into these impressive conceptual packages so that we can put them up on the shelf for adoration by us and our peers. But that’s not what Bach wanted. Shakespeare wrote enormously complicated plays, but he wrote them for the public. Bach and Shakespeare both wanted their music to be heard. When music becomes privatized, it loses its tether to the general public. So how can we be surprised when the public turns elsewhere?”

—Eastman Commencement Address, May 2013

Eastman faculty and alumni from across musical genres noted that Lowry was expert in posing questions—questions that brought clarity to debates about the mission of the school, the role of the arts in society, and the relationship of music to other arts and to other human enterprises. And he got people to join in conversations.

Maria Schneider ’85E (MM), a Grammy Award–winning jazz composer, recalls Lowry approaching her for her thoughts on Eastman’s jazz program. “He was enthusiastic to hear ideas, and I came at him with a thousand of them. Sometimes he would joke, ‘Oh, my God, here comes Maria! Run!’ But he liked it. He knew I would be throwing out a thousand things I could imagine happening at Eastman.”

Mark Volpe ’79E, managing director of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, stepped up his involvement with Eastman at Lowry’s request, joining the Eastman National Council, an advisory board Lowry was eager to expand, and accepting an invitation to deliver the school’s commencement address in 2009.

“He was so wonderful in laying out the case for the school and for alumni involvement,” says Volpe. “Relationships”—with alumni, arts leaders, University leaders, with faculty, and with stakeholders in Eastman’s home of downtown Rochester—“will be his ultimate legacy.”

James VanDemark, professor of double bass and cochair of the strings, harp, and guitar department, says Lowry’s openness to people and ideas set a positive tone at the school.

“Something that was very evident about Doug from the day he arrived on Gibbs Street was that he had a very broad view of the world. He had a completely informed, nuanced view of the musical world, and the world in general,” VanDemark says. “He was remarkably devoid of any kind of artistic prejudice.”

Born in Spokane, Wash., in 1951, Lowry grew up in Idaho. He played piano, guitar, and trombone as a youth, and married his high school sweetheart, Marcia. He started out as a pre-med student at Idaho State University, but quickly changed course, transferring to the University of Arizona to study music theory and composition. He pursued graduate study at the University of Southern California’s music school, began his professional career there, and rose to associate dean and chair of the conducting department. Before coming to Eastman in 2007, Lowry was dean of the University of Cincinnati’s College-Conservatory of Music.

Among the close-knit community of music school leaders, Lowry’s death was mourned not only as a personal loss, but a loss to the profession as well.

Joseph Polisi, president of the Juilliard School, noted that arts institutions either rise or fall together. And what happens at one matters elsewhere, especially if that one is a place like Eastman.

“Eastman’s historic role is extremely important,” Polisi says, adding, “it’s not every day that you get a guy like Doug.

He had a really excellent sense of vision about where the arts profession should be going. And he coupled that vision with the ability to implement, which is a rare combination.”

Robert Blocker, dean of Yale’s school of music, reflected on the relationship with Lowry that he enjoyed for nearly 25 years.

Through their wide-ranging conversations, “There’s not much we didn’t touch on,” he says. And while their roles as music school deans demanded they occasionally competed with one another, Blocker says, “We encouraged each other. We were friends working for the same larger goals.”