Features

PASSION AND ABILITY: Burgett, known familiarly as “Dean B,” brings a vibrant enthusiasm to his interactions with students in and out of the classroom. (Photo: Adam Fenster)

PASSION AND ABILITY: Burgett, known familiarly as “Dean B,” brings a vibrant enthusiasm to his interactions with students in and out of the classroom. (Photo: Adam Fenster)It’s a mid-September morning, and members of the Eastman School of Music’s freshman class arrive at Hatch Recital Hall. They’re about three weeks into the semester, just long enough to have had a taste of Eastman life, just short enough for everything still to be new. They chat and shift in their seats.

And then Paul Burgett ’68E, ’76E (PhD) takes the stage. His voice—sonorous, animated—his gregariousness, his humor, and his sheer joy in seeing them capture their attention immediately.

Coming to the Eastman School, he tells them, is for him “coming home”—because, 50 years ago, he, too, was an Eastman freshman, a young violinist from St. Louis.

“I was a ‘regional treasure,’ ” he tells them. “Just like you—you’re all regional treasures.”

Rochester, he thought, was a detour on the way to being a national, even an international treasure. Upon his arrival at the school, Burgett went to the practice rooms. “It was just us freshmen who were here,” he says, “and I took my fiddle out, put my music on the stand, and began to play the Vitali Chaconne. Big piece, muscular. It makes you sound like a million dollars. I’m not really practicing—I’m playing it. And I leave the practice room door open, just a little bit.”

The students laugh knowingly.

“I wanted all within earshot to appreciate this regional treasure who had arrived,” he says. That feeling lasted until the other undergraduates, graduate students, and faculty returned: “At which point, I have a moment of epiphany. My whole notion of talent gets radically redefined. I pull that practice room door shut, I push that handle down—you all know—put a piece of paper over the window and a bag over my head so no one can see who’s making all that noise!”

A young woman in the audience murmurs in response, seemingly unaware she’s speaking aloud: “That’s how I feel.”

Once again, Burgett has made a connection—warm, affable, empathetic—with a student. He has made such connections thousands of times, and not just with students, but also with colleagues, alumni, community members—really, with everyone he meets.

“I think that he is so many people’s mentor, and we don’t all know each other. It’s like Friends of Bill Clinton: Mentees of Paul,” says Melissa Mead, the John M. and Barbara Keil University Archivist and Rochester Collections Librarian.

This academic year marks half a century since Burgett arrived in Rochester, and most of those years have been spent with the University. Fifty years would be notable enough—but in that half century, Burgett has come to embody the spirit of Rochester. “In many ways, he’s the face of the University,” says attorney John LaBoda ’02, ’03 (T5).

“He has personified this institution in a way that not only makes him a beloved figure, but that also makes others love the University more. That is quite a gift,” President Joel Seligman says.

COMMAND PERFORMANCE: Burgett addresses Eastman freshmen in this year’s version of his legendary speech, “The Fiery Furnace.” In it, he tells them about his own experiences as a new Rochester student, and about the journey that awaits them. (Photo: Adam Fenster)

COMMAND PERFORMANCE: Burgett addresses Eastman freshmen in this year’s version of his legendary speech, “The Fiery Furnace.” In it, he tells them about his own experiences as a new Rochester student, and about the journey that awaits them. (Photo: Adam Fenster)The speech Burgett gives to this year’s Eastman freshmen— nicknamed “The Fiery Furnace,” and to an earlier generation of students, “The Black Ball”—had its origins in a brief talk he gave as a sophomore, when the planned speaker, Eastman’s then director, was stranded at Chicago’s O’Hare Airport. It’s “a sharing of personal history, a true sharing of himself, that is frankly remarkable. And the notion that he has sustained it for thousands of students in multiple decades is extraordinary if not unique,” says Samuel Huber ’99, ’04M (MD).

With “The Fiery Furnace,” Burgett welcomes students to campus and tells them about the journey on which they’re embarking. Undergraduate education is about the “confrontation with ideas,” a process that’s sometimes fun, but more often hard, soul-searing. It’s like stepping into a furnace, he tells them: hot, intense, at times terrifying. “But you will step out of that furnace strong, tempered like steel.”

And then he makes a promise: “We will not abandon you. We will never abandon you.”

As generations of students attest, he’s a man as good as his word. The guarantee he makes on behalf of the University is a personal credo, too. Burgett cares fiercely about other people, and the charisma and natural gift for performance—the full force of his personality—that he displays on the Hatch Hall stage is matched in power by his capacity to listen and observe, to enter into dialogue, and to express and act on a deep and genuine affection for the people around him. “He is one of the most generous and kindhearted men I’ve ever known,” says John Covach, chair of the College’s Department of Music.

Burgett earned three degrees—a bachelor’s of music with a major in music education and violin in 1968, a master’s in music education and violin in 1972, and a doctorate in music education in 1976—at Eastman. After working as executive director of the Hochstein School of Music and Dance in Rochester in the early 1970s, as a music teacher in the Greece, New York, Central School District, and as an assistant professor of music at Nazareth College, Burgett returned to Eastman in 1981 as its dean of students. He has been at the University ever since, rising through the ranks of the administration as vice president and University dean of students, then vice president and general secretary and senior advisor to the president. Today, having dropped only the title of general secretary, he is semiretired—but you would never know it. He is a constant presence on campus and in the city of Rochester: teaching, advising students, consulting with the president, meeting with community members, and serving on the boards of local institutions.

He has flourished in all that he has put his hand to, but he eschews the title of administrator. “I’m a musician and a teacher,” he says.

That 50 years have passed is a surprise to him. “That’s not been relevant to me, because I hang around students who never age, do they? They’re always 18 to their mid-20s or so, some a little older. And when they get to the end of their studies, they leave and are replaced by newcomers. So I forget how old I am, until I look in the mirror and see my father looking back at me—at which point it’s, well, startling, I suppose.”

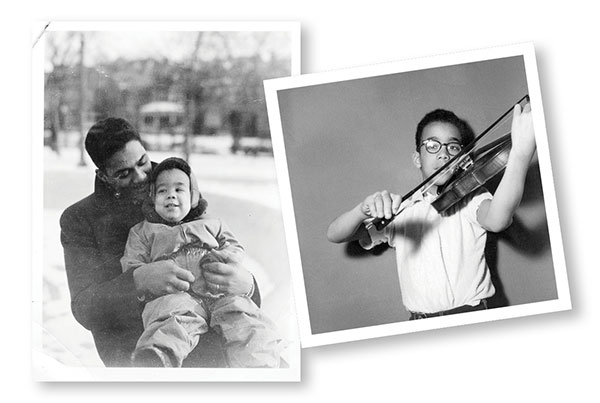

EARLY DAYS: Burgett as a toddler, cradled in the arms of his father, Arthur Burgett (above), and as a budding violinist at

age nine (right). (Photos: Photo: Courtesy of Paul Burgett ’68E, ’76E (PhD))

EARLY DAYS: Burgett as a toddler, cradled in the arms of his father, Arthur Burgett (above), and as a budding violinist at

age nine (right). (Photos: Photo: Courtesy of Paul Burgett ’68E, ’76E (PhD))Burgett was born in St. Louis, the eldest of six and the son of two musicians. “There was always music in the house,” he recalls. “It was an integral part of my family’s life.”

But the harmony in his home contrasted with the discord he found outside it. Of his hometown at the time of his youth, he says: “Racist is not too strong a word. St. Louis was a segregated town. I’m the product of a biracial family: my father was African American and my mother was Italian.” Anti-miscegenation laws prevented Burgett’s parents from being married in Missouri, so they went to Illinois for their wedding before returning to St. Louis.

“My early years were before the dismantling of the racist legal architecture that enabled greater access,” Burgett says. As a high school student, he played violin with the St. Louis Philharmonic, a semiprofessional orchestra, and took a music theory course at Washington University at St. Louis. On his way home, he would walk through an “affluent” neighborhood. “What stands out in my mind from those long walks home was the police car pulling up, most often unmarked,” he remembers. “And as soon as I saw it, I knew exactly what was happening. I’d always have my fiddle and my book bag, and I’d put both down, and put my hands on the hood of the car, and spread my legs while they frisked me and interrogated me. In one instance, my parents told me, I was actually arrested and taken to the police station. My father came to get me. I must have repressed that memory completely because I can’t recall it.”

Burgett cites a passage from W. E. B. DuBois’s The Souls of Black Folk as personally meaningful. The young DuBois, growing up in Massachusetts, took part in a school game distributing visiting cards with the other children. “The exchange was merry, till one girl, a tall newcomer, refused my card, —refused it peremptorily, with a glance. Then it dawned upon me with a certain suddenness that I was different from the others; or like, mayhap, in heart and life and longing, but shut out from their world by a vast veil,” DuBois writes in his 1903 book.

Burgett knew—knows still—that veil. When he was eight, his parents moved the family from an African-American neighborhood to one that was “in transition,” he says. “One of my new friends there was a fellow named Dennis, who was white and whose father was on the faculty of Washington University. So Dennis, my brother, and I got it into our heads to go to the movies on a Saturday—it was probably cartoons. The three of us made our way to the movie theater, and Dennis put his 35 cents on the counter and got his ticket and went into the theater. And then my brother and I went up to the ticket window, and the woman—I can still picture her—the woman in the ticket window looked down at us and said ‘We don’t allow your kind in here.’ And in what I can only describe as a nanosecond, it was—nothing more needed to be said—the veil descended, and I knew there was once and forevermore a cleavage between her and us, between them and us. And so that was a seminal moment in my growing up.”

His parents worked to provide Burgett and his siblings an intellectually rich environment and to shield them from prejudice. “We were a working class family with high aspirations for the children,” he says. “My parents accomplished so much with very few resources. They provided a stable home and sought opportunities for us, especially in the arts and education. They surrounded us with a world of smart, talented, and interesting people, music, the arts, and ideas that enabled our social, cultural, and intellectual fluency. And, looking at my brother and sisters, I think that produced adults of stature and outstanding achievement.”

At the same time, his parents “formed a safety net around us, to try to protect us, recognizing that it’s not really possible to do that completely, but they did the best they could. There always worked in the back of our minds concern about what was safe and what wasn’t safe, where we could go and couldn’t go, and the fact that we were an interracial family made us peculiar because that just didn’t exist much at all back then. So I lived this sort of split life.”

Experiences of his youth have left a lasting mark, Burgett says. “The anxiety associated with that continues to this day, in very subtle ways. For instance, when I was a boy growing up, going into a business establishment and having the businessperson say, what are you? Are you colored or are you white? Which always puzzled me—I thought, if you can’t tell, you know? I mean, please. But my answer was always, ‘I am a Negro.’ We didn’t have the word biracial back in those days. ‘I’m a Negro.’ And if I had any anxiety that I might be rejected, I wouldn’t go in. And so the way that still plays itself out is, there’s a voice in the back of my head—it’s a soft voice any longer—but it’s a voice where I will still hesitate. And in our travels—travel is a great thing for my spouse and me—I have been known to say to her, go in and be sure that it’s OK. Because that voice is still there, and the anxiety associated with rejection on the basis of the accident of birth, I still carry that inside of me. The veil, once it descends, doesn’t easily lift. I have been able to pull it apart and look through it, and develop social and cultural fluency as a result of doing that, but the veil still has an effect.”

Burgett’s parents met at the Catholic church, St. Elizabeth’s, where his father’s family were parishioners and his mother taught and played the organ. His father, who hadn’t graduated from high school, was drafted into the army to serve in World War II. After the war, he returned to St. Louis and earned his diploma while in his 30s. From there he went to St. Louis University, where he earned a bachelor’s degree in music education and voice.

“My father was an artist, and what he really wanted to be was what Eastman alumnus William Warfield became,” Burgett says, making reference to the famous African-American concert baritone and 1942 graduate, with whom his father once performed. “My father was well-known in St. Louis and the Midwest, and in fact he was the first African American to sing with the St. Louis Symphony.” But while he yearned for a musical career, he soon had six children to support—which he did with a job as a building mechanic for the telephone company. There was a divided quality to his father’s life, too, Burgett says. “He finally had a college education, but opportunities for black males especially were limited. And what he really wanted to do was get on the stage and sing.”

His father left for work every day in a suit and tie. One day, he forgot his lunch, and Burgett’s mother sent her two sons, Paul and his brother, Peter, to deliver it. “We got into the building and we called him to come up, and he came up—and he was wearing his work uniform, which was overalls. It was the only time I’d ever seen him like that, before or since. I was shocked. That wasn’t the dad I knew. He took enormous pride and pleasure in the development of his children, but I think deep inside was a profound sadness that he didn’t have a career in music.”

When casting began in New York City for a traveling company performing Porgy and Bess, Burgett’s mother gave his father money she had saved for him to travel east for an audition. He won a role, but decided not to accept it “because my mother was struggling back in St. Louis with all these children—I think there were maybe four of us by then. He made the decision not to go abroad with the company, but rather to come home and pick up his job with the telephone company, and that’s what he did. He got home late at night. And I can still remember his arrival because it was a moment of total and utter ecstasy that Daddy was home. And as ecstatic as I was, he must have been saddened and depressed by it. But he kept that pretty much to himself. It was just not going to be. He decided that his first responsibility and his first priority was to his family, and so he went back to St. Louis and put his overalls back on.”

Burgett’s mother gave piano lessons in the family home, and Burgett began playing at age five. When he was nine, a family friend and violist with the St. Louis Symphony, Edward Ormond, observed that the boy had good hands for the violin and offered to teach him himself. When Ormond moved to the Cleveland Symphony Orchestra when Burgett was 12, he was devastated to lose his teacher, but continued his study at the community music school. By the time he was 16, Burgett had been selected to attend the International Congress of Strings, a summer music program at Michigan State University. Just two string players were chosen from each of the 50 states, plus Mexico and Canada. It was the same year that he joined the St. Louis Philharmonic and that he was accepted as a student by St. Louis Symphony concertmaster Melvin Ritter. Burgett calls the effect of those experiences “life changing.”

He auditioned in St. Louis for the Eastman School. Ritter wrote to Eastman admissions director Edward Easley that Burgett “hadn’t had rigorous training, but the raw material was there, and he works his tail off,” Burgett remembers. He was admitted, and Easley later told him he was “persuaded you would be a fine music teacher.”

Arriving at Eastman was a “watershed moment” on a number of fronts. “I was at the mountaintop, musically,” Burgett says. And he arrived in the fall of 1964, just after the passage that summer of the Civil Rights Act. Surrounded by fellow musicians, he found himself in an atmosphere where he could thrive. “The issue of race took a backseat, and the veil began to rise,” he says. The bonds of similar passions between the students overcame other differences. Eastman allowed him to develop socially in ways not possible for him before, even though Rochester was “still smoldering,” he says, from the 1964 riots that convulsed the city.

“In the environment of Eastman, I took enormous comfort. I didn’t have to look over my shoulder all the time.” He was elected president of the freshman class, and “that stunned me. Qualities of my makeup were unleashed because my classmates accepted me. I can’t even begin to explain how important that was.”

The profound changes Burgett felt were perhaps not as visible from the outside. Vincent Lenti, professor of piano and Eastman School historian, was a second-year faculty member when Burgett arrived as a freshman. He was “very congenial, outgoing, confident. I can’t think of a time when Paul wasn’t Paul,” Lenti says. “He’s not one of those people about whom you say, gee, it’s a miracle he turned out as he did.”

In his “Fiery Furnace” speech, Burgett explains that he chose to stay at Eastman, despite his initial fears that his talents didn’t measure up, because of his love of music. “I was passionate about it. I got to this place, and I found that I didn’t have to explain myself to anybody. It was just simply understood. Music was the totem to which all of us were drawn. I couldn’t think of anything I would rather do than be in this environment.”

Passion is a touchstone of the speech, and he tells the students—eventually leading them in a chorus—words that he believes can guide them through their college years and beyond: “Passion and ability drive ambition.” What you major in, he tells them, isn’t all that important. It’s what you care about, what you feel compelled to do, coupled with the necessary skills, that will lead you to a successful and meaningful life.

“My undergraduate experience was heady and wonderful, and allowed me to grow in ways not possible before,” Burgett says. “My freedom became the centerpiece of my education—and isn’t that what it’s supposed to be?”

After graduating from Eastman in 1968, Burgett was awarded a National Defense Education Act Fellowship to earn a doctorate. He did one year of study, but eligible for the draft in the Vietnam War, he opted instead to join a military band in the Army Reserves, in which he played the tuba. He was executive director of the Hochstein School for two years, and then returned to Eastman for his doctorate.

He thought “long and hard” about his research topic. “I decided that I’d had the best education that a person could hope to have. The musical titans for me were Bach, Beethoven, and Brahms, Mozart, Mahler, et cetera. But I couldn’t tell you what Charlie Parker played, much less whether there were any black classical composers. I didn’t know.” Burgett told his advisor, Paul Lehman, that he wanted to do something that spoke to his heritage. “So he told me to go into the Sibley Music Library and spend the next year reading. Just reading. I remember Dr. Lehman saying to me, ‘I don’t know much about the subject, but we’ll learn together.’” The work, Burgett says, “was irresistible. I couldn’t not do it.”

He spent the next three years writing his dissertation, “Aesthetics of the Music of Black Americans: A Critical Analysis of the Writings of Selected Black Scholars with Implications for Black Music Studies and for Music Education.” It is dedicated to the memory of his father. “My father’s nickname for me, all my life, was Doc. That’s what he called me,” says Burgett, his eyes rimming with tears. “And he would call me Doctor Bones, because I was incredibly skinny as a boy. But then Doctor Bones got shortened to just ‘Doc.’ And when I was a doctoral student, I would say to him, I’m on my way to authorizing your nickname of me. But he died before I finished it. So he got the dedication.”

Burgett took a post teaching violin at Nazareth College in the Rochester suburb of Pittsford, first as a lecturer and then as an assistant professor of music. But in 1981 a new opportunity appeared: Eastman was hiring a dean of students. When Lenti learned that Burgett was interested in the job, he wrote a letter to Eastman director Robert Freeman telling him, “I understand Paul Burgett is applying. Look no further.”

Freeman listened, appointing Burgett. “In the days when I knew him at Eastman, he was close enough to the age of the students that they all trusted him. We all did. And should have,” Freeman, now a professor of musicology at the University of Texas, says. “He came from an atmosphere that was deeply unfair, and Paul has not only survived but conquered brilliantly.”

Colleen Conway ’88E, ’92E (MA), a professor of music education at the University of Michigan, remembers that Burgett—in days long before the Internet—knew each freshman’s name, where they came from, and what they played before they arrived on campus. “That little piece of showing care and interest—it makes me tear up, because I feel like that really set the teacher that I then became.”

As president of the Eastman student association, Conway saw Burgett’s responsibilities up close. “I remember getting a window into what his job was like—meetings starting at 7:30 in the morning. And I could see the schedule, and when I’d go in at 1, I’d think, how did he make me feel special when he’s seen 20 other people today? You’ve got to be there in the moment, and he’s just really good at that.”

As dean, he influenced students profoundly without having classroom time with them, she recalls. “And that’s really powerful. Somehow he’s able to do that just through hallway conversations. He wasn’t teaching me classes—he was teaching me to be a person. There are more important things than the musical learning, and that’s something I learned from him. And I think you could say that across campus—there’s more important learning in ages 18 to 22.”

Burgett’s intuitive sense of how to relate to other people was a priceless gift in his work as dean, Freeman says. “Something we don’t teach college students enough is how to read other people’s body language and listen very carefully to what they’re saying. Paul understood what motivated people, which of course is what a dean of students has to do: act not just as a disciplinary agent but as a friend who can help a student find his own best way.”

Essential, too, was Burgett’s own experience at Eastman, and his abiding affection for the place. “The foundation of his education was performance and applied music but he also had a strong interest and background in academics, pedagogy, and communicating with people,” says Marie Rolf, senior associate dean of graduate studies at Eastman and professor of music theory. “It gave him a great knowledge base; he had immediate understanding of people coming from all aspects of music and deep empathy because he’d been there.”

Adds Betsy Marvin, professor of music theory: “It was palpable how much he loved Eastman. He seemed to be part of the whole fabric there.”

Nevertheless, after seven years, Burgett felt that he had done all he could as Eastman’s dean of students—just at the time that the University was looking to create a similar position.

Dennis O’Brien, president from 1984 to 1994, says undergraduate education was a focus of his presidency. “I decided we needed someone who was at the vice-presidential level, so that he was dean for all students, at Eastman and the River Campus. I wanted a student-oriented person who was a member of the president’s cabinet, so that I could get immediate feedback on student affairs.”

In a survey of students about their perceptions of the University, one student responded that “Rochester was a ‘cold and distant place,’ and there was a hint that the University was cold and distant, too,” O’Brien says. “And Paul is the least cold and distant person I’ve ever met.”

“He took the place by storm. Paul is such an enthusiastic person. He loves people, and people love him in return,” says G. Robert Witmer Jr. ’59, chair emeritus of the Board of Trustees, who had led a committee examining the River Campus’s structure for student activities and affairs. At that time, he had identified Burgett as “the epitome of the type of person we are looking for.”

O’Brien was pleased with his choice. “He did a number of things I admired greatly: he liked being called Dean Burgett. He thought Vice President Burgett sounded kind of pompous. And he wanted to set up shop in Wilson Commons, where the students were. That’s right on—this is someone who wants to be known as a dean, and he’s going to move in right where the students are.”

You can hardly imagine him anywhere else. “Students are my most favorite people in the world,” Burgett says. “I adore them. I love students. My idea of the closest thing to great potential and to efforts at human perfection, for me that’s to be found in students.”

And while he feels that regard for them en masse, his attention has always been specific and particular, too. “Even though there are thousands of students at the University, people always felt he took an interest in every single one of them,” says Malik Evans ’02, now a bank business growth manager who marvels at Burgett’s “boundless energy. I don’t know if I know anyone to this day who has that energy.”

Logan Hazen, associate professor at the Warner School and former director of residential life, was the first person Burgett hired in his new position. His “contagious enthusiasm, his upbeatness—I mean, there’s a message in there,” says Hazen. Even for students meeting with Burgett in a disciplinary capacity, “they could always see Paul valued them, Paul cared for them, and what he was doing was the right thing to do.”

Part of his success in doing that may stem from Burgett’s determination to know and interact with people beneath their appearances and defenses—a product, perhaps, of his own youth. His goal has always been to “gain admission to the backstage” of students’ lives. Much of all our lives, he says, is theater: that which we perform when others are watching us. “But the backstage is where real life is lived, where the costume comes off and where the human being emerges in all of her or his realities.”

For 24 years, his assistant was Beverly Dart. “Bev and I developed over time a theory of our lives with students, and the theory was very simple: when a student came to us, regardless of the reason—and sometimes they came to us and I had to be the sheriff; sometimes they came to us with tragedy—our first goal was to treat them in a way so that when they left, they felt no worse than when they arrived, and if we were really successful, they felt better. Our second goal was that in their conversation with me, whatever the issue was would be defined more precisely. Oftentimes people come thinking the problem is one thing, but the problem may be something else. So spending the time—and that’s what it’s about—it’s spending time with the person across from you long enough to gain clarity about the issue. And then the third goal was to assist the person across from me in articulating options for moving forward. A plan.”

“He’s a good listener, and I think he always made students feel important when they came to see him,” says Donna Brink Fox, associate dean of academic and student affairs at Eastman. “He was careful to listen and counsel them in a way that never came across as too directive. Not ‘You need to do this’ or ‘You’d better do that,’ but ‘Have you thought about. . . ?’ He even does that with me. To me, that’s just his style, whether he’s talking to an undergraduate who’s questioning life as a musician or talking to a colleague or a faculty member. I think he’s the same, and that’s a great quality to have. It’s genuine.”

As University dean of students, Burgett took what had been an underdeveloped student affairs program and made it robust, Hazen says. At Eastman, he had planned the Eastman Student Living Center; at the River Campus, he improved programs at the Interfaith Chapel, Wilson Commons, University Health Service, Counseling and Mental Health Services, Residential Life, and Athletics and Recreation. Through it all, he was an unflagging presence at student events.

PIZZA PARTY: Chatting with academic advisees at one of his signature pizza get-togethers. “Eleven months a year, if a student group said, ‘We’re having pizza at 11 o’clock at night; can you make it?’ Paul would be there,” says Logan Hazen, former director of residential life. (Photo: Adam Fenster)

PIZZA PARTY: Chatting with academic advisees at one of his signature pizza get-togethers. “Eleven months a year, if a student group said, ‘We’re having pizza at 11 o’clock at night; can you make it?’ Paul would be there,” says Logan Hazen, former director of residential life. (Photo: Adam Fenster)“Eleven months a year, if a student group said, ‘We’re having pizza at 11 o’clock at night; can you make it?’ Paul would be there—even if he had an 8 a.m. meeting with the president,” says Hazen. “But day one of the 12th month, Kay”—Burgett’s spouse, Catherine Valentine, now a professor emerita of sociology at Nazareth College—“would take him to other places around the world. That’s how he kept his battery going. It’s hard to keep up with the man. One of my favorite stories: Kay found a village somewhere in rural Vietnam, and she was headed to an artifact shop there. They arrived in an area remote enough that there was no electricity. And then Paul hears a voice calling, ‘Dean Burgett!’ It was an American-Vietnamese Rochester student, so excited to see him there.”

Not all the responsibilities that fall to Burgett are as happy. “He probably makes the hard parts of his jobs over the years look easy because you don’t see them. Dean of students isn’t just a cheerleader for the student experience; there are brass tacks there that are unpleasant for anybody,” says Huber, now a psychiatrist.

Burgett has “all that surface charm and energy, but when there were emergencies, he was always there. Paul would be there and take care of it, and talk to the parents, if that was necessary. He was very hands-on with the kinds of emergencies that would come up,” O’Brien says.

Burgett recalls one instance when a student was experiencing an emotional crisis. Her mother had come but was having difficulty communicating with her. The mother called Burgett and asked him to join them. The student “was crying very, very hard. I took her in my arms, and just rocked her. And hummed. Told her, ‘It’s going to be all right. It’s going to be OK.’ So we stayed in that situation for, I don’t know, an hour, maybe, and then she said, ‘I’m ready to go to the hospital.’ That’s what it took. The human situation is complex, but we gain nothing from abandoning people.

“I often have said to parents, just be patient, just wait—and above all, do not abandon the person. With our students, with novice adults, we must not ever abandon them. They must know, as they try to develop enough confidence to become fully enfranchised adults, they must know that we’re here, and that we’re about creating an environment of safety.”

Burgett doesn’t just make students feel safe—reaching back to his own early life, he expands their sense of who they can be.

“A lot of folks will tell you, when he’s talking with students, he’ll call you Doc. The student will say, I’m not Doc, and he’ll say, don’t worry, you will be,” says Hazen.

It’s something many alumni mention. “Dean Burgett would always refer to us as Doctor so-and-so—he set the bar that anything you want to do is possible, and this is a place where you can make that happen,” says Tiffany Taylor Smith ’91, founder of the consulting company Culture Learning Partners.

In 2001, Burgett ended his tenure as dean of students, becoming vice president and general secretary and senior advisor to the president, then Thomas Jackson. It’s a position he continued when Seligman took over the presidency four years later. Burgett trimmed his duties in 2011, stepping down as general secretary to the Board of Trustees.

MUSIC AND IDEAS: Burgett doesn’t think of himself as an administrator. “I’m a musician and a teacher,” he says. “Paul lives classes,” says President Seligman. Here Burgett responds to students’ rhythm patterns in his History of Jazz course. (Photo: Adam Fenster)

MUSIC AND IDEAS: Burgett doesn’t think of himself as an administrator. “I’m a musician and a teacher,” he says. “Paul lives classes,” says President Seligman. Here Burgett responds to students’ rhythm patterns in his History of Jazz course. (Photo: Adam Fenster)He continues to devote considerable time to teaching. Each fall, he teaches either the History of Jazz or Music of Black Americans. “His courses are extremely popular,” says Covach. Adds Seligman: “There are a lot of people who teach classes. Paul lives classes.”

The passion he feels for working with students is borne out in his teaching, in the “disciplined attention and enthusiasm for the music and ideas that I try to bring to my students in the classroom,” he says. Rochester medical student Jarrod Bogue ’10 took the jazz course as a sophomore, drawn by his interest in the saxophone and the chance to be taught by Burgett. “I’d heard he was a good professor—that’s the feeling on campus. He’s one of the really good ones. He puts so much effort into each lecture, and they keep building. I loved the class.”

Partial retirement also provides Burgett more time for the travel that he and Valentine have long enjoyed, visiting much of the world in the past 35 years.

In October, the Board of Trustees resolved that the University’s intercultural center would hereafter be known as the Paul J. Burgett Intercultural Center. It’s a fitting honor. The center brings students together to work with and learn from those from other cultures, backgrounds, beliefs, socioeconomic statuses, sexual orientations, and more. In its resolution approving the naming, the Board of Trustees praised Burgett as a “tireless advocate for justice and equity for all.” Burgett was delighted with the honor, writing in a note of thanks that he is “an intercultural product . . . from birth.”

“The really interesting thing to me about Paul is his way of bringing people together, seeing growth opportunities in others, and connecting people to both his vision and the vision of others. I see that as one of his most masterful skills. Many people will talk about his charisma, his energy, but that underlies it,” says Huber.

Burgett uses that skill of bringing people together on behalf of the Rochester community, too. “His name always comes up when people think about how they want to connect with the University. They say, is Paul Burgett still there? Let’s call him. They know he cares about Rochester. He’s connected to Rochester, and he believes in Rochester,” says Evans, a member of the Rochester City School District Board of Education. Burgett has served such groups as the Urban League, the Mt. Hope Family Center, the Rochester Arts and Cultural Council, the United Way of Rochester—even the Zoning Board of Appeals for the city.

“He has touched the Rochester community as deeply as anyone I know,” Seligman says.

“Paul was our ambassador to Rochester forever, I guess. That’s a big part students and staff didn’t see a lot,” says Hazen. “All the community activities, all the boards, all the times representing the institution as somebody from the University the community trusted—because we weren’t always trusted. But Paul’s a man of his word, and if you worked with him, you trusted him. He didn’t talk much about it. I don’t think he toots his own horn as much as he toots it for other people,” says Hazen.

Says Mead: “You ask any one person what Paul does, and they say X, and maybe Y, but they don’t know the full alphabet of everything he’s doing.”

“I can’t remember any time that Paul’s ever asked for anything back,” Huber says. “The amount of pizza he’s eaten, lunches he has purchased, advice he has dispensed just by listening and reflecting: I don’t think he ever asks for anything back. Genuinely I can’t remember a time when he’s said, Sam, I need a favor. And you’ve got to think his favor bank, there’s a good balance there. And I don’t know anybody who would say no to him.”

And now Burgett, in the latest phase of his career, has taken on the task of immersing himself in the University’s history, poring over documents in the Department of Rare Books and Special Collections, speaking to alumni, new faculty, and students about what the University stands for and how it came to be.

“I’m having a grand time in this new part of my life, that I didn’t anticipate, as sort of the University’s storyteller: where we came from, who our predecessors were, on whose shoulders we stand, and our responsibilities as stewards of their legacy.”

“He knows more about a lot of the documents than I do,” says Mead.

“There’s a part of what Paul has meant to this University that really needs to be emphasized—he is the institutional memory of the office,” says Seligman, referring to the president’s office. “And he has an almost artistic sensibility to the nuances of history. When I want to understand someone in our past, I turn to Paul.”

In his talks, Burgett makes reference to the University’s history of “inspired, effective, and generous leadership,” Mead says—adding that the phrase applies equally well to him, with a special emphasis on generosity. “I think there’s a lot of people who wouldn’t be where they are without Paul’s advice, his encouragement, and his caring—and his ‘inspired, effective, and generous leadership.’ ”

It’s a phrase that complements his motto from the “Fiery Furnace” speech: passion and ability drive ambition. You can put those two phrases together as guiding principles, she says: the first part is for you; the second is how you fit in the University, in the world, in life.

It’s not surprising that Burgett would have some perspective on how to create such a fit. In the years since he was a small boy in Missouri, he has found a way to carve for himself a place in the world—in the community, in the University, in the lives of generations of students, faculty, staff, and alumni—that is unique. Lively, funny, insightful, caring: “He is a presence,” says O’Brien.

“There are very few people you can maintain as a hero through the really tumultuous portions of growing up,” Huber says. “Who you see as a hero when you’re 18 is different than when you’re in your 30s or 40s or 50s—but he, for me, maintains that status.

“If I had Paul all figured out, there would be two of us—I would do what he does.”