CARNEGIE ON CAMPUS: Opened in 1911 on the Prince Street Campus as the first home of Rochester’s engineering programs, the Carnegie Building (above) eventually became a residence hall for students in the College for Women (below). After a fire this winter, the building, owned by private developers, was torn down. (Photo: University Libraries/Department of Rare Books, Special Collections, and Preservation)

CARNEGIE ON CAMPUS: Opened in 1911 on the Prince Street Campus as the first home of Rochester’s engineering programs, the Carnegie Building (above) eventually became a residence hall for students in the College for Women (below). After a fire this winter, the building, owned by private developers, was torn down. (Photo: University Libraries/Department of Rare Books, Special Collections, and Preservation)On January 27, 2015, an early morning fire gutted the Carnegie Building on the University’s original Prince Street Campus. Although the building had not been University property for almost 60 years, the event was widely noted by alumni, staff, and Rochesterians for whom it had long been a familiar sight on Goodman Street between University and College avenues. A note from Deanne Molinari ’58 captures the concern: “Carnegie was the dorm and first exposure to the University for many women students. For the Class of 1958, it has resonance because we were the last class of women to enter on the Prince Street Campus before the merger with the College for Men. I believe classmates and others would be interested in the building’s fate.”

(Photo: University Libraries/Department of Rare Books, Special Collections, and Preservation)

(Photo: University Libraries/Department of Rare Books, Special Collections, and Preservation)In 1905, Andrew Carnegie promised the University $100,000 toward the construction and furnishing of an engineering building—the seventh building on the Prince Street Campus—if the University could raise the same amount to be added to its endowment to support a Department of Applied Sciences.

According to Arthur May’s A History of the University of Rochester, President Rush Rhees was interested in expanding the sciences at the University. The Eastman Building, with facilities for physics and biology, was nearing completion, which meant that George Eastman was unlikely to contribute; another major donor at the time, Hiram W. Sibley, had already committed to renovate the library in Sibley Hall, which had been initially funded by his father.

Sibley suggested that Rhees contact John D. Rockefeller Sr. Previous direct appeals to Rockefeller had not borne fruit, but working with alumnus Frederick Taylor Gates, Class of 1877, who headed the Rockefeller-funded General Education Board, Rhees and others secured a portion of the necessary matching funds—and perhaps equally important, the foundation was laid for the relationship that would culminate in a far larger grant to fund the School of Medicine and Dentistry in 1920.

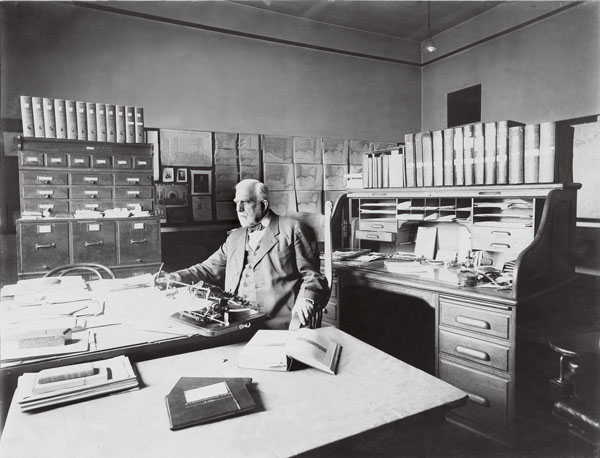

FAIR PLACE: The last professor hired by President Martin Brewer Anderson in 1888,

geolo-gist Herman Fairchild was a fixture in the Carnegie Building even after retiring

in 1920. (Photo: University Libraries/Department of Rare Books, Special Collections, and Preservation)

FAIR PLACE: The last professor hired by President Martin Brewer Anderson in 1888,

geolo-gist Herman Fairchild was a fixture in the Carnegie Building even after retiring

in 1920. (Photo: University Libraries/Department of Rare Books, Special Collections, and Preservation)Almost four years would pass before the money was in hand and plans could move forward. A front page article in the September 30, 1909, Campus proclaimed that Millard Ernsberger, Class of 1888, had been hired to lead the new program of study. Course offerings included statics and kinetics, drawing, hydraulics, thermodynamics, and materials science, but would not be all technical: Ernsberger, the Campus reported, “is an earnest believer in the value of a broad cultural education as a foundation for special work.”

The building was described in the 1911–12 Undergraduate Bulletin as having a footprint of 63 feet by 123 feet: “[a]ll steam and water piping, and all electric conduits throughout the building are exposed, thus forming a valuable adjunct to instruction.” The basement housed engineering laboratories, including steam engines, while the first floor had lecture and recitation rooms, a computing room, and a cement-testing lab. Three large drafting rooms with “multi-part-desks” for technical drawing, recitation rooms, and a blueprint room occupied the second floor. The first students to receive degrees with a major in mechanical engineering graduated in 1914.

The River Campus opened in 1930, and included a new engineering building (named in 1949 for Joseph Gavett Jr.). Carnegie was renovated to provide spaces suitable for instruction in psychology, sociology, and geology. Steam pipes were replaced with radiators, plumbing and electricity were upgraded, and fire escapes were added.

More changes occurred during World War II. For the first three decades of its existence, the College for Women was largely a commuter school. Then between 1930 and 1944, there was a 700 percent increase in resident students. A total of 288 women—more than one half of the enrollment—sought a residential college experience. To help accommodate the growing enrollment, the upper floor of Carnegie was converted to house 60 women, at a very modest 80 square feet (or less) per student, including bed and nightstand.

With the merger of the colleges in 1955, most of the University’s properties on the Prince Street Campus were sold and a variety of businesses and their staffs have occupied the spaces. Andrew Carnegie’s name continues at the University as a professorship in physics, established in 1965 and currently held by Professor Joseph Eberly.

The building was razed after the remaining shell was declared an imminent danger to the public at a City of Rochester hearing in March. If the developer doesn’t repurpose the lintel, inscribed with the word “Carnegie,” it may be “returned” to the University.