In Review

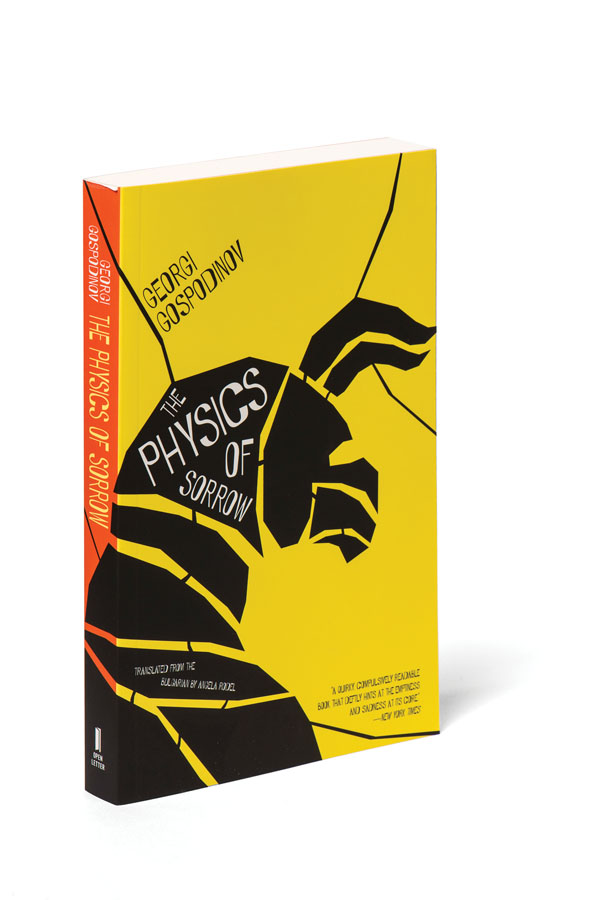

OPEN BOOK: Georgi Gospodinov’s The Physics of Sorrow, translated from the Bulgarian by Angela Rodel, is a new Open Letter novel. (Photo: Adam Fenster)

OPEN BOOK: Georgi Gospodinov’s The Physics of Sorrow, translated from the Bulgarian by Angela Rodel, is a new Open Letter novel. (Photo: Adam Fenster)Open Letter, the University’s nonprofit literary translation press, sold its 100,000th book this fall. The publishing house is also a partner in the University’s program in literary translation studies. Seven years after the press’s founding, and with 78 books in its list, director Chad Post says that he hopes to broaden Open Letter’s geographic perspective even more.

What’s the focus of Open Letter?

We go for a balance of two kinds of authors: classic authors that we know will sell well and new voices. For the well-established authors—like Marguerite Duras, Elsa Morante, and Juan José Saer—we like to bring some of their books back into print and to publish ones that have never been translated.

And we’re trying to find new voices that have never made it into English before. That’s what our NEA [National Endowment for the Arts] funding is for. It’s our “Emerging Voices” series.

Are the emerging voices all contemporary?

Not necessarily. Lúcio Cardoso from Brazil, who has never been published in English before, wrote what’s considered to be the greatest Brazilian gay novel. He died in the 1960s. He was a huge influence in Brazilian literature, and we’re publishing his novel Chronicle of the Murdered House. On the other hand, we’re also publishing Josefine Klougart—a young Danish author who was a finalist for the biggest Nordic prize twice by the age of 30.

But they’re both voices that haven’t been experienced by American readers.

How do you ensure geographic variety?

It’s something we look at. There are certain areas that we’re not good at yet, such as the Middle East and Africa. The systems there are different. For example, there aren’t agents. It’s much more time-intensive than it is when working with someone from France or Germany. So far we’ve published one South African author. And the same with India—there are almost no books that are published in translation in the United States from Indian authors, and that’s another area we’d like to find someone from.

We haven’t hit all the regions yet, but it’s pretty wide. We have Chinese authors, all the western European countries, a lot from Latin America and South America.

We’re doing a series of books as part of a Danish women writers series. In tracking what gets published in translation, I’ve found that in the past eight years, only 26 percent of translated books published in the United States are by female authors. That’s pretty bad. Incredibly low. We’re publishing five books over the next five years in the Danish women writers series. And it looks like we’ll do the same with authors from South Korea.

There’s only one major country over the past eight years that’s had more female authors translated than males, and that’s Finland. And it’s all crime novels.

Are there other presses that do what Open Letter does?

There are a lot of people who publish literature in translation, at least one book—but presses who publish a significant number, there are probably 10. They don’t all do exclusively translations [as Open Letter does], but they do a number of them. Oddly enough, the press that does the most translations of anyone is Amazon Crossing. They published 128 books over the past eight years—and most of that in the past four years.

Has globalization changed things?

There’s not a lot of coverage of translations, but when there is, it tends to be in a different tone than it used to be. It used to be more dismissive—“this isn’t the ‘real’ book,” or, “if you’re going to read translations, here’s a good book.” Now it’s more positive and more generally accepting of international literature as a valuable part of book culture as a whole.

All these books that have broken through—such as Elena Ferrante’s Neapolitan novels and Stieg Larsson’s “Millennium trilogy”—have shifted the conversation away from “We don’t want to read books from Finland or Sweden” to “These are interesting.” That’s changed the conversation dramatically.

What are the hallmarks of a good translation?

The main thing I look for is voice, that you can feel the voice and style of the original book in the translation. With a good translation, you can hear and feel the voice and know right away that you’re on sure footing as a reader.

It’s easier to note what can be bad about it—a lot of inverted clauses that are mimicking the original syntax, wooden and flat dialogue. When it feels mechanical, it’s just not working. Translations can be completely accurate, but not feel like they’re “written.” They don’t feel organic—and a good translation feels organic when you read it.

What’s ahead for Open Letter?

We’ve had a lot of authors we’ve worked on who have won big awards recently, and I think one of these years we’re going to have a book that sells 8,000 copies. We’re in the right position to be able to do that. It’s nothing you can predict. Things just have to lock into place right, and when that happens, it will be really important.

And I think we’ll hit more regions of the world. But mostly we’ll continue to help train translators through the University, working with students and getting them out into the workforce. A lot of our translators have had success recently, and that’s gratifying—getting published, getting grants, awards, and residencies. They’re the things you need to do to move from a college graduate who does translations to a career translator whom people automatically go to. A number of them have fallen into that category.

You published Voices from Chernobyl by this year’s Nobel laureate in literature, Svetlana Alexievich, when you were with Dalkey Archive Press. Any lessons for Open Letter in that?

A Nobel Prize isn’t something you can really plan or prepare for. I think if you look for high-quality books from a vast number of voices and areas, you’re just going to stumble upon the right one at the right point in time.