Features

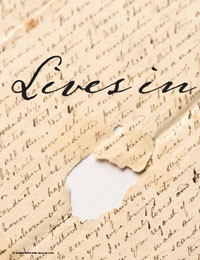

TREASURE TROVE: One of the most extensive collections of 19th-century American family letters known to exist, the William Henry Seward Papers include correspondence such as an 1834 letter from Seward to his wife, Frances. The back shows the tears that wax seals sometimes made in the paper, adding to the challenge that transcribers face. But the family often saved the seals, which can hold the missing words. (Photo: Adam Fenster)

TREASURE TROVE: One of the most extensive collections of 19th-century American family letters known to exist, the William Henry Seward Papers include correspondence such as an 1834 letter from Seward to his wife, Frances. The back shows the tears that wax seals sometimes made in the paper, adding to the challenge that transcribers face. But the family often saved the seals, which can hold the missing words. (Photo: Adam Fenster)Picture an attic groaning with papers saved over more than a century.

That’s the sight that greeted Glyndon Van Deusen ’25, a professor of history at Rochester from 1930 to 1962, when he was invited to the top floor of the Seward family home—once the house of leading 19th-century American politician and Secretary of State William Henry Seward—in Auburn, New York, in the 1940s.

Seeing ‘Sewords’: A Glossary

The average undergraduate doesn’t talk a lot about “victuals” or “habiliments.” But for students contributing to the Seward Family Digital Archive, those are the kinds of words they encounter. To bridge the gap between the centuries, computer science major Demeara Torres ’18 has devised a database, called “Sewords,” that defines terms from the period that participants find in the letters.

‘My Dear Henry . . .’ : A Transcription

In a 1832 letter (with transcription), Frances Seward tells her husband, William Henry, then in Albany, New York, about the family Christmas. He was almost always away for the holiday.

“I shall never forget the sight that met my eyes in that attic,” he later wrote. “Great masses of material, largely letters to William Henry Seward, were there, some in trunks, boxes, and valises, some bound up in bundles, all covered with the dust of decades.”

And that wasn’t the end of it. Van Deusen—who was writing a biography of Seward’s friend and political ally Thurlow Weed— began to bring University librarian John Russell with him on his visits to Seward’s aged grandson, William Henry Seward III. Russell describes the papers he then encountered: “many trunks and boxes in the basement and attic of the house, and in storage rooms in the barn.”

Rochester vied with Yale and the Library of Congress for the papers; ultimately, Seward’s grandson chose Rochester as their home, and in 1951, at his death, the University’s Department of Rare Books, Special Collections, and Preservation became the repository of the papers.

Now an intergenerational team of “citizen archivists”—led by Thomas Slaughter, the Arthur R. Miller Professor of History, and with the wide-ranging support of librarians at the River Campus Libraries—is working to bring to light the extensive holding of family papers in the collection. Slaughter calls it “one of the best Victorian-era, intact family collections in the nation.”

The letters exchanged by family members are the focus of the Seward Family Digital Archive Project, now in its fourth year and supported by a grant from the Fred L. Emerson Foundation. A searchable public website is scheduled to launch in April, making available 20 years’ worth of letters, from 1822 to 1842, drawn from the collection and four related manuscript collections at the University, the Seward House Historic Museum in Auburn, and a small private collection held by a Seward descendent.

The William Henry Seward Papers is one of the largest manuscript collections that the library holds and among the most often cited. Seward, who lived from 1801 to 1872, was a trial attorney, a New York state senator (1831–1838), governor of New York (1838–1842), U.S. senator (1849–1860), and secretary of state (1860–1869). He was the frontrunner for the Republican nomination for president in 1860, only to be sidelined in favor of someone more moderate in his support of abolition: Abraham Lincoln. Today he is best remembered for his decision to purchase Alaska—at the time, called “Seward’s Folly.” He was also attacked in the assassination plot that killed Lincoln. The collection of Seward’s papers, both professional and personal, includes 230 linear feet of materials, 150,000 items, and 375,000 pages.

When librarians first organized the papers in the 1950s—in what must have been a near-Herculean effort—archivists assumed that historians’ interest would center on the papers that relate to government. Even when portions of the collection were microfilmed in the 1980s, attention was still given, almost exclusively, to the state papers.

“The family letters themselves were separated out of the general correspondence into three cabinets and not microfilmed along with the rest of the collection,” says Alison Reynolds, the William Henry Seward Project archivist in the special collections department. “There are also 31 boxes relating to family memorabilia, personal papers, and household finances, and those weren’t microfilmed at all. So even in 1981 when they did the microfilm, they still thought the family part wasn’t going to be as interesting or as frequently used.”

But since the collection arrived on campus in the mid-20th century, historical priorities have changed, with the emergence of social and cultural history and the growth of interest in family history, gender studies, and investigations of race and class.

There are 5,000 family letters, running to a total of 20,000 pages, says Slaughter. Household account books, diaries, travel journals, scrapbooks, and other items add another 5,000 pages.

The project involves making digital images of each page of the selected letters, and transcribing and annotating them. The completed digital archive will feature in the range of 25,000 digital images, including some of the Seward family’s photographs.

Carrying out the project is a three-pronged team. The first two groups in the team are students in Slaughter’s course related to the project, and student employees of the project, including both undergraduates and graduate students. They work in a room in the Digital Humanities Center that they’ve dubbed the “War Room,” and framed photos of team members’ faces, superimposed on 19th-century figures, flank the large computer monitors around the room.

Each fall semester, the students in Slaughter’s course, The Seward Family in Peace and War, learn the history of the influential and extended family and gain firsthand experience with digitization and documentary editing. Mary Ann Mavrinac, vice provost and Andrew H. and Janet Dayton Neilly Dean of River Campus Libraries, calls the Seward Family Papers Project “an embodiment of the River Campus Libraries’ future in working with students” as it equips them “with 21st-century digital media skills while giving them direct access to one of our most rare and unique collections.”

The third group is less expected: volunteers, including residents of the Highlands at Pittsford, a University-affiliated retirement community. Their participation is part of a pilot program to expand the project beyond the University and into the community. The residents of the Highlands, located in the Rochester suburb of Pittsford, bring a singular skill to the project, one not readily found in people in their late teens and 20s: an intimate familiarity with both letter writing and reading cursive handwriting.

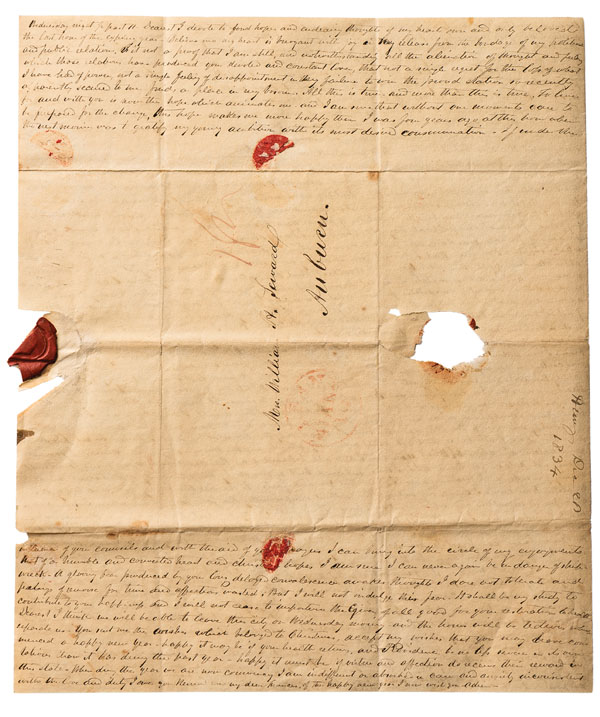

AT WORK: Retired American history librarian Margaret Becket volunteers as a transcriber and annotator for the project. She calls the language of the letters “formal, even when they’re writing to their families. It’s not stiff, but it’s dignified.” (Photo: Adam Fenster)

AT WORK: Retired American history librarian Margaret Becket volunteers as a transcriber and annotator for the project. She calls the language of the letters “formal, even when they’re writing to their families. It’s not stiff, but it’s dignified.” (Photo: Adam Fenster)Students in Slaughter’s course have typically struggled with the longhand they find in the letters. But the volunteers don’t.

No longer widely taught in schools, cursive writing isn’t second nature to undergraduates today. “A lot of them have no familiarity with it,” says volunteer and retired University librarian Margaret Becket, “and even the ones who did learn it in school don’t use it nearly as much, and don’t even see it very much.”

“We all had the Palmer Method,” says volunteer Lyn Nelson, who lives at the Highlands with her husband and describes herself as “an original Katharine Gibbs girl,” from the business school that, beginning in the Great Depression, trained women for careers in business, with instruction in typing, shorthand, and other office skills.

“It’s hard to believe that they don’t teach it anymore. It makes one feel sort of sad,” says Allan Anderson, a retired hospital administrator who, in a long and geographically varied career, held several positions at Highland Hospital and was an executive director of Strong Memorial Hospital from the late 1960s through the 1970s. Retired in 1996, he and his wife, Pauline, have lived at the Highlands since 2012.

Becket, Nelson, and Anderson all note that the ease of reading the writing varies with the penmanship. And archivist Alison Reynolds observes that 19th-century handwriting isn’t quite familiar cursive.

“It’s a lot more extravagant. They use a lot more loops, and there’s a letter that kind of looks like an ‘f’ but it’s a double ‘s’ [called a ‘long s’], and so that can be tricky as well. And n’s and u’s, or o’s and e’s—they all can get confusing. And it’s not as neat, because they weren’t using the high-quality pens we have, either.”

In fact, pen technology and handwriting methods get hands-on treatment in Slaughter’s course, where students try the kinds of pens that Seward family correspondents would have used. They also study handwriting primers and theory books that teach them proper posture, hand position, and letter formation.

“It gives you perspective,” says Demeara Torres ’18, a computer science major from New York City. “You realize this is what they had to do.” She took the course—which changes its thematic focus every year—last fall. But she has worked on the project since her first day of college, after meeting Slaughter during a scholarship interview when she was still in high school.

Handwriting is only part of what makes reading the letters challenging. The paper is thin, with writing from the other side bleeding through. The ink is sometimes thick and blotchy, and big blobs of ink fell from the pen onto the page; other times, the ink is faint and spidery. To economize on paper, letter writers would occasionally cover a page in script both horizontally and vertically. Sometimes several people would write parts of a letter, or one letter would contain different sections for different recipients. There were no envelopes; instead, correspondents would fold the paper so that part of the page became the outside. And sealing wax would tear words away when the letter was opened, sometimes leaving gaping holes in the letters—though the Sewards often saved the wax, which can still hold the missing words. Slaughter and his assistants digitize and transcribe those, too.

Creating a “documentary edition” according to the standards of the Association for Documentary Editing has “only ever been done with a stable staff of PhDs,” Slaughter says. But this project has a transient student staff, and now, a corps of volunteers, most of whom are new to the world of archives.

Most of the country’s major documentary editorial projects began in the 1950s, says Beth Luey, past president of the American Association for Documentary Editing and a former editor of the Adams Family Papers at the Massachusetts Historical Society. They were research projects, and students weren’t involved. “But Tom Slaughter has demonstrated that you can do this. There are people in the editing community who thought that was true, but couldn’t prove it.”

Maintaining editorial standards requires careful coordination, and that’s built into the project, too. “The most important thing is transcribing accurately and annotating as fully as possible,” says Slaughter. Because students are constantly graduating and moving on, or completing the course, the students involved “are always just learning the history, the vocabulary, and the people,” he says.

Documented best practices are the key to maintaining continuity, so that students can train the students who will replace them, without ever meeting them. That pedagogy—guidelines, resources, syllabi, and student research—will be shared, along with the documents, on the digital archive.

Even a decade ago, annotation on such a scale would have been far more cumbersome, if possible at all. Online databases—newspapers, city directories, genealogical resources, and more—have allowed project workers to identify more than 4,000 people mentioned in the letters, along with an extensive list of Seward pets, from Brownie the canary to Snip the spaniel. The team has created a database of “Seward People and Places.” It aims to be comprehensive, identifying every person, place, and literary work mentioned in the letters.

Working on the project has “opened up a more technological aspect of history,” says Sarabeth Rambold ’18, a history and political science major from Manchester, Vermont. “You think of history as something that’s oriented in the past, but this is very driven toward the future. It’s an interesting combination.”

Rambold took the course in the fall of her freshman year, and then took a job with the project. This year she has been working with the volunteers at the Highlands, especially Anderson.

“I’d never have gotten to work with people so different from myself, age-wise, if I hadn’t started working here,” she says.

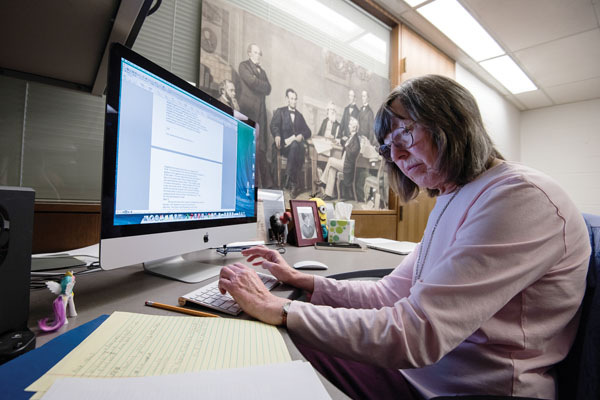

ACROSS GENERATIONS: Collaboration manager Lauren Davis (left), a history PhD student, and Sarabeth Rambold ’18 (middle) discuss transcriptions with volunteers Lyn Nelson and Allan Anderson at the Highlands at Pittsford, a University-affiliated senior community. (Photo: Adam Fenster)

ACROSS GENERATIONS: Collaboration manager Lauren Davis (left), a history PhD student, and Sarabeth Rambold ’18 (middle) discuss transcriptions with volunteers Lyn Nelson and Allan Anderson at the Highlands at Pittsford, a University-affiliated senior community. (Photo: Adam Fenster)So far, the students have mainly been helping the volunteers with technology.

While the technology learning curve for the volunteers has been steep, Lauren Davis is impressed with their determination. She’s the first-year history doctoral student who is managing the volunteer arm of the project. After earning her master’s degree, she taught history students for three years at Wayland Baptist University in her home state of Texas. She worked with students from their teens to their 60s.

“I became interested in what it brings to the table when you have intergenerational education,” she says.

While the volunteers are adept at reading handwriting, the students bring computer savvy. “It’s a balance,” says Davis.

As a little girl, volunteer Lyn Nelson remembers, she’d go to the library in the summertime and fill her bag with biographies. Now she finds a direct connection to history in the Sewards’ correspondence.

She transcribed a letter in which Seward describes seeing the Washington Monument, already standing 15 feet above the ground.

“I adore that!” says Nelson. “It just tickled me. It gave me shivers all over.”

She says that “the whole project gives me energy, delight, interest. I find it—how should I phrase this? I’m eager to get to it, and eager to learn from it, and it adds something, a new dimension, to my life.”

For volunteer Allan Anderson, who was raised on a farm in Chautaqua County, New York, it also resonates with an old dimension of his life. His deep familiarity with the western New York terrain where various Sewards and their friends lived and traveled is an asset to the project, says Davis. Anderson’s great-great-grandfather even purchased the family farm from the Holland Land Company, which once owned most of what is now western New York. Seward was an agent for the company—but the Anderson farm was not bought “from Mr. Seward, as far as I know,” he says with amusement.

Connections, though, are at the heart of the project—between people and across time and distance. The letters give students “a whole different sense of the kinds of connections that people made with, and through, their letters,” says retired librarian Margaret Becket.

In many ways, the Sewards—who even annotated the outside of letters—are an archivist’s dream, says Serenity Sutherland, a doctoral candidate in history, a 2014–16 Andrew W. Mellon Fellow in the Digital Humanities, and the project manager. “If you can imagine—a whole family that saves everything from 1776 to the 1880s. They saved everything.”

At the Seward House, home to many of the material objects they saved, “everything” includes ordinary household items, gifts from abroad, and telegrams and even bloody bed sheets from when Seward was stabbed by former Confederate soldier Lewis Powell as part of the Lincoln assassination plot. “When you combine these [objects] with the letters in which they’re mentioned—it’s just a really complete collection that I don’t think many other paper collections have,” says Sutherland.

And in their letters, the Sewards discuss some of the most vital political topics of their day, including abolition and women’s rights.

Seward used his governorship to bring reform to education, immigration, prisons, and law in New York. In 1850, the outspoken abolitionist gave his famous “higher law” speech, in which he declared that “. . . there is a higher law than the Constitution.” He and his wife, Frances, sheltered fugitive slaves in their Auburn home as part of the Underground Railroad and contributed financial backing to Frederick Douglass’s North Star newspaper, which Douglass published in Rochester.

But Frances was perhaps even more reform-minded than her husband, and the letters are a record of their exchanges. She raised funds for antislavery causes. She raised the niece of Harriet Tubman while Tubman worked for the Union Army as a nurse and a spy. She supported the Married Woman’s Property Act, a law passed in New York state in 1848. She was “very moral and religious,” says Sutherland. “She had a lot of strong beliefs—beliefs that, when they were younger, she believed he held, too. But when he became more involved in politics, William Henry Seward lost some of the ardor that he originally had for abolitionism—or at least, he tempered it with wanting to be a good politician, and to be successful.

“Frances never did. She was always strong in her belief that it was absolutely morally wrong for a nation that espoused freedom to be enslaving people, and she never wavered from that. So she would write intellectual arguments to William Henry, telling him why he was wrong for the speech that he made about promoting leniency for slaveholders, or something like that. She did a lot of negotiating in her letters.”

Daughter Fanny’s diaries and correspondence, alongside her library, which is conserved at the Seward House, provide an unparalleled glimpse into the life of a 19th-century American teenage girl. “Fanny’s ambitions to be a writer, her experiences in Washington, D.C., where she had friendships with a famous actress and with the children and spouses of the leading politicians of the day, and her firsthand experience of major historical events are documented only in our collection,” Slaughter says.

The project is beginning to expand beyond the family letters, to include not just items like diaries but also the correspondence of close friends.

“We’re finding that family stories aren’t always confined to the family members. A lot of family stories get told to close friends. And so we’re thinking that we have to have the papers of these friends [which are also held in Special Collections], too, in order to really tell the family story,” says Sutherland.

The stories were read with urgency at the time, and remain almost as compelling today.

“Receiving letters was so important to the family members,” she says. “They beg each other to write to them. They say, please write to me—I haven’t heard from you. Frances especially begs William Henry all the time to write to her. She’s saying, I haven’t gotten a letter from you in one week. You must be sick; I know you’re sick because you wouldn’t not write to me. They guilt each other into writing.”

But the fear was real. Before antibiotics, a sudden fever could take a healthy person away in the time between letters. “That was part of the function of letters: letting people who love you know that you’re still OK, because people could get sick so quickly, so unexpectedly,” Becket says.

Seward maintained a punishing travel schedule in the United States and abroad that kept him away from his family frequently and for long stretches. Their lives, in a very real sense, were lived through their letters. One letter from Fanny to her mother in 1864 runs to 26 pages, as she adds the happenings of day after day after day. Sutherland calls it a “mini-novella.”

And reading the letters is, in many ways, like reading a novel, says Becket. The dramas they describe—from arguments over a nation’s slaveholding to grief over a baby needlessly lost to smallpox to delight over the antics of squirrels, in a letter from an aunt to Seward’s youngest son—may be of interest to any reader, not just to historians of 19th-century America.

“You’re always getting surprises, and shifts in relationships,” Becket says.

“William Henry Seward was so famous, but when you read his letters, you see he’s just a normal person, dealing with normal family things,” says student Sarabeth Rambold. “I like how accessible it makes historic people.”

“To have this focus on the family papers puts [Seward] and his work in a context that we don’t have for very many other, even very important, Americans, and I think that’s the value of it,” Becket says. Through the letters, “we know more about people’s lives and how they got through each day. Their relationships, their priorities, can tell us so much more, not just about Seward but about people in his social class, and the value system of the whole culture.”

“We don’t usually think of historians as explorers, but they are,” says Luey. “It’s exciting to see things people haven’t seen before, or they’ve gotten wrong, or that you just see differently. We don’t get many chances to do that in our lives, and I think it’s important for someone to have the chance to do that at least once in college.

“There are a lot of ‘ah-ha’ moments” in learning, but usually they involve someone else’s discovery, she says.

“To have one that’s your very own is a treasure.”

The Seward Family Digital Archive is scheduled to go online on April 13, at sewardproject.org.