In Review

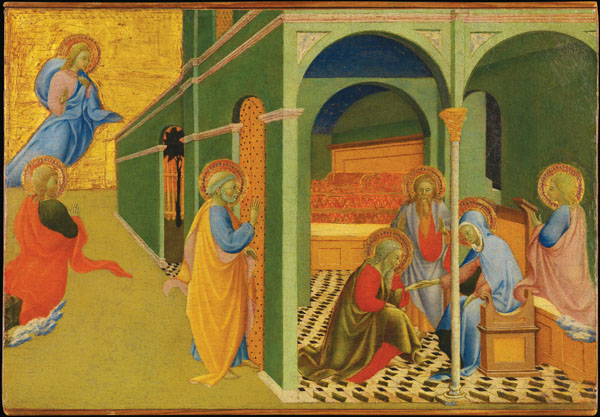

LEAVE-TAKING: Critic Jane Tylus compares the gesture of Saint Peter in a Renaissance painting by Sano di Pietro to the “posture of the poet who is ready to say goodbye to a poem but hasn’t sent it off yet.” (Photo: Berenson Collection, Villa I Tatti, Florence, reproduced by permission of the President

and Fellows of Harvard College;

Photo: Paolo De Rocco, Centrica srl, Firenze)

LEAVE-TAKING: Critic Jane Tylus compares the gesture of Saint Peter in a Renaissance painting by Sano di Pietro to the “posture of the poet who is ready to say goodbye to a poem but hasn’t sent it off yet.” (Photo: Berenson Collection, Villa I Tatti, Florence, reproduced by permission of the President

and Fellows of Harvard College;

Photo: Paolo De Rocco, Centrica srl, Firenze)Saying good-bye—in life and in art—isn’t easy.

For Jane Tylus, a professor of Italian studies and comparative literature at New York University, the idea that there’s a convergence between both forms of parting became clear when she saw a 15th-century painting that she describes as “probably the most beautiful and thought-provoking painting I’ve seen in a long time.”

It was Congedo della Vergine, by Sano di Pietro, at Villa I Tatti, near Florence. The painting depicts a non-Biblical story of the Virgin Mary’s leave-taking from the disciples as she prepares to be reunited with Jesus Christ. In one panel of the painting, Saint Peter stands at the threshold of her house—there to say good-bye, but hesitating at the moment of doing so.

“This gesture of Saint Peter, who knows what is in front of him, but isn’t ready to go in just yet—this, to me, captures the posture of the poet who is ready to say good-bye to a poem but hasn’t sent it off yet,” says Tylus, who also is faculty director of the NYU Center for the Humanities. Like Saint Peter, she says, the artist stands before a work, declaring, “‘I’m about to say good-bye—but not yet. I can’t bear to say good-bye yet.’”

The painting led Tylus to what she calls a “new way of thinking” about “what a lot of visual and literary art is doing in the Renaissance.”

As this year’s keynote speaker for the Ferrari Humanities Symposia, Tylus outlined some of her new ways of thinking about how artists and others depicted rituals of separation in early modern Europe. Tylus’s lecture, “Saying Good-bye in the Renaissance: Leave-Taking as a Work of Art,” was one piece of a three-day visit that involved a variety of activities, including a meeting with humanities graduate students, a public talk on the future of the humanities, and a presentation and roundtable conversation on the city in history with faculty and students from a multidisciplinary undergraduate course, Cities: Contested Spaces.

In her recent work, Tylus has written about the most significant women writers in Renaissance Italy, including Catherine of Siena, Lucrezia Tornabuoni, and Gaspara Stampa. Thomas Hahn, a professor of English and the organizer of the symposium, praises her skill as a translator whose work “extends far beyond linguistic expertise and elegance” in books such as Reclaiming Catherine of Siena: Literacy, Literature, and the Signs of Others (Chicago, 2009)—winner of the Modern Language Association’s Howard R. Marraro Prize—and Siena: City of Secrets (Chicago, 2015).

“Her purpose in these books wasn’t just to recover the past but to situate these writers alongside the monuments and poetry that we all regard as a common heritage—for example, the work of Dante, Petrarch, and Michelangelo,” he says. “She ‘translates’ not just the words of individual writers, but a full sense of an age, a city, a work of art.”

The topic of Tylus’s keynote address was spurred by personal experience: coming to terms with the loss of parents and reflections on mourning and grieving. But her scholar’s mind soon ranged beyond her private sadness to thoughts about how contemporary beliefs and practices surrounding loss differ from what they were centuries ago.

A practicing Catholic, Tylus says she realized that “in my life, there’s a lot more continuity with the Middle Ages. There are sharp differences that Protestantism introduces to Catholic practices of not really saying good-bye.”

With the Protestant Reformation came enormous departures from Catholic religious practice, including a rejection of the idea of purgatory, where souls would be purified before ascending to heaven. Practices such as allowing the living to shorten, through paying for indulgences, the deceased’s time in purgatory meant that relationships continued, in some fashion, after death, Tylus says.

At the same time, artists were carrying on a long poetic tradition of pausing before the end of a work to contemplate the act of letting go. With many names—among them, the congedo in Italian and the envoi in French—the end of a poem was often a place where poets would turn to address the work itself and consider what might happen to it once it leaves them.

Michelangelo’s non finito, or unfinished, sculptures for the tomb of Pope Julius II—itself unfinished—are one example Tylus points to of a similar phenomenon in the visual arts. The figures “look like they’re imprisoned in the stone because they’re not finished,” she says. Late in his life, Michelangelo wrote a series of sonnets about his art’s lack of value when it comes to his life beyond death. “It’s a sad kind of rejection of the meaning he’s had as an artist, as he’s also saying good-bye to that life itself in his poems,” she says.

Produced a century later, Shakespeare’s work is “riddled with questions about when and how we say good-bye to loved ones,” she says. One particularly well-known example is Polonius’s comically excessive leave-taking from son Laertes in Hamlet, but Tylus finds particular meaning in the famous closing speech of Shakespeare’s final play, The Tempest. Prospero implores the audience to “release me from my bands/With the help of your good hands.”

“There’s a real sense that Prospero is going to die and is calling to the audience for life beyond death,” she says.

For Michelangelo, who was heavily influenced by some tenets of the Reformation, these radically new ideas struck at the roots of a sense of human community extending beyond death.

What was at stake, Tylus says, was nothing less than “the worth of a work of art in the face of the Reformation.”

Ferrari Humanities Symposia

Jane Tylus was the 2016 keynote speaker this spring for the Ferrari Humanities Symposia, an annual event designed to highlight the broad interdisciplinary connections that are fundamental to a liberal arts education. Tylus is the director of NYU’s Center for the Humanities and a professor of Italian studies and comparative literature.

University Trustee Bernard Ferrari ’70, ’74M (MD) and his wife, Linda Gaddis Ferrari, established the symposia to broaden the liberal education of the University’s undergraduates, enhance the experience of graduate students, and expand the connections of University faculty with other scholars from around the world. Established in 2012, the series has hosted speakers including Anthony Grafton and Stephen Greenblatt.

—Kathleen McGarvey