From the Archives

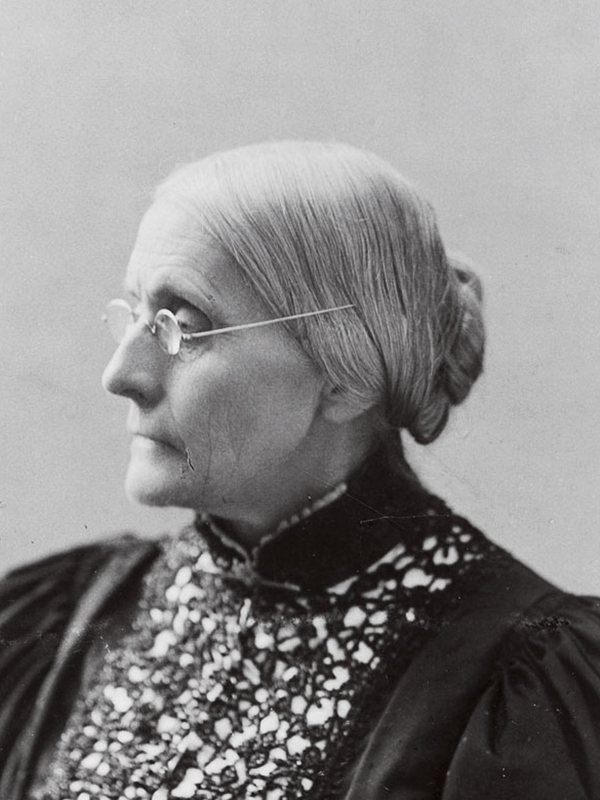

DOORS SWING OPEN: A month after winning admittance for women to the University of Rochester, Anthony took a carriage ride through campus, writing later in her diary: “l thought with joy, ‘These are no longer forbidden grounds to the girls of our city. It is good to feel that the old doors swing on their hinges to admit them.’ ” (Photo: University Libraries/Department of Rare Books, Special Collections, and Preservation)

DOORS SWING OPEN: A month after winning admittance for women to the University of Rochester, Anthony took a carriage ride through campus, writing later in her diary: “l thought with joy, ‘These are no longer forbidden grounds to the girls of our city. It is good to feel that the old doors swing on their hinges to admit them.’ ” (Photo: University Libraries/Department of Rare Books, Special Collections, and Preservation)On a lazy Saturday afternoon in early September 1900 the executive committee of the Rochester Board of Trustee was handling a bit of routine business: approval of a young biology instructor’s request for a raise (to $1,200 per annum).

Next, the committee was to discuss the purchase of some new equipment for the physics lab.

“At this point,” tersely record the minutes of that meeting, ‘the Committee were waited upon by Miss Anthony, Mrs. W. A. Montgomery, and Mrs. Bigelow, representing the Women’s Coeducational Society.’ “

What the minutes do not record is that it was an unexpected (and, for at least some of the participants, unwelcome) interruption. Before their visitors had left — and the trustees could get back to granting Instructor Merrell his raise — the course of the University of Rochester had been irrevocably altered. Its 50-year history as a small liberal arts college exclusively for men had come to a dramatic close.

How Susan B. Anthony pledged her $2,000 life insurance policy in a successful eleventh-hour bid to accomplish that end is an old story. But in this year of anniversaries [updated for 2020] — 200 years since Anthony’s birth, 120 years since “Susan’s girls” entered the University, and 100 years since women got the vote — the story bears telling once again.

It had taken a decade of work. From 1890 on, several local women’s organizations had been pressuring University officials to relax its men-only restriction. Anthony joined the skirmishes in October 1891, when University President David Jayne Hill and his wife, Juliet, attended a large reception for suffragist Elizabeth Cady Stanton at the Anthony home on Madison Street.

Bypassing small talk, Stanton let fly that “it was rather aggravating to contemplate the University’s fine buildings and grounds while every girl in the city must go aboard for higher education.” Juliet Hill had just given birth to twins, a boy and a girl — prompting President Hill to respond, mildly but encouragingly, that if God was willing to place the sexes “in such near relations” for nine months before birth, “perhaps they might with safety walk the same campus and pursue the same curriculum in their later years.”

Trustees, and particularly (and vociferously) alumni for the most part saw otherwise: Five years later, Hill had left the University, and the young women of the city were still attempting to edge inside.

A breakthrough came on June 14, 1898, when the trustees voted to admit women on the same condition as men effective “when the women of Rochester shall raise the necessary funds.” The estimated cost of the expanded faculty and facilities deemed essential: a daunting $I00,000 — a sum that, in the closing years of the 19th century, could have purchased very comfortable, brand-new homes for about 50 local families.

(In all fairness, it should also be noted that the University was still a small, struggling college, recouping a much small portion of tuition and fees, even than it does today. Officials believed that the additional money was necessary if they were to accommodate a sudden surge in enrollment of whatever gender.)

A committee of prominent local women immediately set to work, to limited success. Two years after they started, in June of 1900, they reported to the trustees: Although they finally had $40,000 in hand — and were hopeful of another $10,000 — the bucks, unfortunately, stopped there.

After yet another lively discussion of the merits of coeducation and the limits of the physical facilities on campus, the board members relented and halved the required funds. Women would be admitted at the beginning of the fall semester, “provided $50,000 is secured in good subscriptions by that time.” The deadline was set for September 8, the date of the executive committee meeting.

Through the ensuing summer months, according a sympathetic reporter at the Democrat and Chronicle, the fundraisers “walked the streets,” soliciting donations and organizing “fairs, fetes, and entertainments” for the cause. It was discouraging work: “Men whom they expected would come down with thousands begged off with paltry subscriptions like $5.”

“Then something happened,” continued the D&C account. “Susan B. Anthony, full of years and worldwide respect, threw herself into the breach.”

Anthony — with the national cause of “woman suffrage,” as it was called then, uppermost on her mind — had played a minor role in the local campaign. Trusting that her fellow committee members were doing their job, she was out of town on another of her grueling lecture tours until just a few days before the deadline.

Committee treasurer Fannie R. Bigelow called Anthony on the telephone on Friday evening of that week to deliver the bad news. One: the deadline was tomorrow. Two: Bigelow and Anthony were the only committeewomen in town at the moment. Three: every wealthy partisan in the area had been contacted, and the fund was still short $8,000. And four: there was little hope of an extension from the board.

At this point, any normal person could have thrown up her hands and gone on upstairs to bed. (The weather had been unbearably hot, mind you, offering another quite sensible excuse to abandon the struggle.) But it was precisely on occasions like this that Anthony, with all her derring-do, earned her stars. After a wakeful night of sorting through her options , the 80-year-old activist put on her bonnet and went to town.

Charity began at home, with her sister Mary, who had planned to bequeath $2,000 to the University if it became coeducational. Susan urged her to give the money now or coeducation might never happen. And so Mary put down the first $2,000. Next Anthony and Bigelow took a carriage to the home of a Sarah Willis, a woman who had supported the feminist cause for nearly 50 years to secure the next $2,000.

Then the going got harder.

Some prospects were not at home, others unsympathetic to the cause. After a meeting with one of the city’s richest women, who begged off by citing her “many expenses,” Anthony got in the carriage, dropped down on the cushions, and, as they drove away, exclaimed, “Thank heaven I am not as poor as she is.”

George Eastman also turned her down — “flatly refused,” she wrote in her diary. But he had a better excuse: He had just given $20,000 to Mechanics Institute (now Rochester Institute of Technology), and thought that was “good work” enough. (It would be four more years before he made his first gift to the University.)

Dogged and desperate fundraiser that she was, Anthony continued her rounds, eventually extracting another $2,000 from her friend the Reverend William Channing Gannett and Mary Lewis Gannett, and then, finally a guarantee of the last $2,000 from the aging, ever-generous Samuel Wilder.

With the pledges in hand, Anthony and Bigelow raced to the trustees’ meeting at the Granite Building downtown and, joined by committee leader Helen Barrell Montgomery, asked to speak to the trustees. “It was quite evident that their appearance was a surprise,” Anthony’s biographer, Ida Husted Harper, writes gently.

Her voice “shaking with excitement,” as Harper records, Anthony laid out the details of the pledges. After consulting amongst themselves for a few moments, the trustees replied that they would accept all but the $2,000 from Wilder because of his precarious health (meaning that, if he died before payment, his estate could not be held for the money).

Even Anthony was stunned — but, gathering her considerable wits, she rose, advanced to the table where the men were seated, and announced: “Well gentlemen, I may as well confess —I am the guarantor. But I asked Mr. Wilder to lend me his name so that this question of coeducation might not be hurt by any connection with woman suffrage. I now pledge my life insurance for the $2,000.”

The dowry was paid — at a high cost to Anthony, who the next day suffered a stroke that caused her lose her speech for a week. One month later, when she was able to go out in a carriage again, she asked to be taken through the University campus. That night in her diary she wrote, “l thought with joy, ‘These are no longer forbidden grounds to the girls of our city. It is good to feel that the old doors swing on their hinges to admit them.’ “

Years later, one of those girls, Vera Chadsey Twichell ’04, reminisced about the day Papa came home with the evening papers and gave her the news that she was about to realize her “fairy-tale dream” and “actually go to college”:

“I shall never forget his call to me to see the headlines saying that dear, blessed Susan B. had pledged her life insurance to make up the last thousand dollars. My father said to me, ‘On Monday morning, you go and register at the college.’ “

“Dear, blessed Susan B. . . . “ The words ring strangely to our modern ears. Accustomed to the granite profile, that mythic icon of feminism, we revere Susan B. Anthony for what she achieved and let slip the real woman behind the achievements. Can we recall her?

A place to start might be the celebrated life insurance policy (which, incidentally, was returned to her when the fund later went over the top). It was taken out in 1855 when she was 35, with the New York Life Insurance Company. Edward M. Moore, a western New York surgeon (and, as it happened, president of the University’s Board of Trustees in September 1900), described her in the medical certificate: “Height, 5 ft. 5 in. . . . [C]haracter of respiration, clear resonant, murmur perfect; heart, normal in rhythm and valvular sound; pulse, 66 per minute; disease, none. The life is a very good one.”

Anthony was a tall woman for her era. Sturdy and stalwart, she was blessed with a constitution that could withstand the stress of 19th-century travel, which she loved, and the strains of constant speechmaking, which she loathed. (“It is terrible martyrdom for me to speak,” she once wrote to her mother. Be that as it may, she later estimated that over the preceding 45 years she had delivered some 75 to 100 public lectures annually — and that wasn’t even counting speeches before state and federal lawmakers.) In contrast to the habitually hurried Americans of the late 20th century, she slept about nine hours a night and lay down for an hour each afternoon.

The Hartford Post in 1869 offered this portrait: “Miss Anthony is a resolute, substantial woman of forty or fifty, exhibiting no signs of age or weariness. Her hair is dark, her head well formed. . . . In speaking, her manner is self-possessed without ranting or unpleasant demonstrations, her tones slightly monotonous. Long experience has taught her a candid, kindly, sensible way of presenting her views, which wins the goodwill of her hearers whether they accept them or not.”

Adapted from a story originally published in the fall 1995 issue of Rochester Revew. Download the 1995 issue.