Features

ANSWERING A CALL: Peter Redmond ’85 says he took to heart President Kennedy’s call to “do for your country” and joined the Peace Corps in 1990. While serving in Honduras, he met fellow volunteer Melissa Estok. The couple married when they returned to the United States. They have three children.

ANSWERING A CALL: Peter Redmond ’85 says he took to heart President Kennedy’s call to “do for your country” and joined the Peace Corps in 1990. While serving in Honduras, he met fellow volunteer Melissa Estok. The couple married when they returned to the United States. They have three children.Peter Redmond ’85 had wanted to join the Peace Corps since seventh grade, when his social studies and English teachers left their jobs to begin volunteer service in Africa.

“Growing up in an Irish-Catholic family, I was well aware of John F. Kennedy saying, ‘Ask not what your country can do for you, ask what you can do for your country,’ ” says Redmond, director of the Center of Excellence in Foreign Affairs Resilience at the US Department of State. “I took that challenge seriously."

But it took years—and a tragedy—for Redmond to join the volunteer government program established by Kennedy in 1961. “After graduating from college, I was unclear about what I wanted to do with my life and tried out different jobs,” he says.

His indecision ended when his cousin died of a brain aneurysm at 25—the same age as Redmond. Redmond calls her death “a wake-up call to follow my dreams.” A year later, he was on a plane to Honduras. He worked at a forestry college in a poor region of the Central American country from 1990 to 1992. He taught workshops, trained midwives and volunteer health workers, and promoted infant vaccinations and rabies vaccinations for dogs.

“The Peace Corps gave me confidence to know I could do anything I set my mind to,” says Redmond, who majored in political science at Rochester. His service also led to his meeting Melissa Estok. She, too, was serving in Honduras. The two married in 1992 and raised three children.

THOSE WHO SERVE: Glenn Cerosaletti ‘91, ’03 (MA) (clockwise from top left) with two children at harvest time in Bolivia in 1996; faculty member Rachel O’Donnell worked with local organizers in Guatemala from 2002 to 2004; and Kate Phillips ’15 (PhD) picnics with friends at a roadside in Madagascar in 2007.

THOSE WHO SERVE: Glenn Cerosaletti ‘91, ’03 (MA) (clockwise from top left) with two children at harvest time in Bolivia in 1996; faculty member Rachel O’Donnell worked with local organizers in Guatemala from 2002 to 2004; and Kate Phillips ’15 (PhD) picnics with friends at a roadside in Madagascar in 2007.At Rochester Right from the Start

Redmond is one of 427 Rochester alumni, faculty, staff, and administrators who have served in the Peace Corps—which celebrated its 60th anniversary in 2021.

As with all corps ambassadors, University community members have volunteered to spend two years abroad after a three-month training period, working side by side with local leaders to tackle pressing challenges—teaching, giving immunization shots, building schools and houses, and supporting other activities.

Rochester community members were among the first of the now 240,000 or so Americans who have served in nearly 150 countries.

Janet Russell ’62 was one of the first volunteer nurses to serve in Pakistan. Penelope (Penny) Carter ’65 worked in Colombia as a teacher and community developer, crediting anthropology classes at Rochester with sparking her interest. William Condo ’65 served in India on health and nutrition projects.

The late Donald Hess was director of the Peace Corps in North Korea from 1970 to 1972 and worldwide Peace Corps director from 1972 to 1974 before working at the University until 1996, first as vice president for campus affairs, and then for administration.

By that year, Rochester had sent 284 alumni to the Peace Corps—eighth most among US colleges with fewer than 5,000 students.

Kennedy Establishes the Corps

On October 14, 1960, after a long day on the campaign trail, John F. Kennedy’s motorcade rolled into the University of Michigan campus in Ann Arbor at 2 a.m. Kennedy was hoping to get some sleep. But when he was met by 10,000 energized students outside Michigan Union, the presidential candidate issued a challenge:

“How many of you who are going to be doctors are willing to spend your days in Ghana?” he asked the students. “Technicians or engineers, how many of you are willing to work in the foreign service and spend your lives traveling around the world? So I come here tonight to go to bed! But I also come here tonight to ask you to join the effort.”

That impromptu speech is considered the birth of the Peace Corps, which Kennedy created through executive order just five months later. The University of Michigan still has a plaque outside the Union entrance marking the occasion.

Kennedy wasn’t the first to call for Americans to volunteer their service in developing nations. Wisconsin Congressman Henry Reuss pushed for a “Point Four Youth Corps” in the late 1950s, and in June 1960, Minnesota Senator Hubert Humphrey coined the name “Peace Corps” while introducing a bill that would send “young men to assist the peoples of the underdeveloped areas of the world to combat poverty, disease, illiteracy, and hunger.”

Neither proposal gained traction. Kennedy’s idea forged ahead. By the time of his inauguration in January 1961, more than 25,000 letters had arrived at the White House from prospective volunteers, mostly college age. On March 1, 1961, the 35th president of the United States signed an executive order establishing the Peace Corps and named his brother-in-law, R. Sargent Shriver, its first director. Volunteers began serving in five countries in 1961, and within six years nearly 15,000 volunteers—most of them fresh out of college—were serving two-year terms in 55 countries.

Not everyone was a fan. Critics mocked the young volunteers, calling them “Kennedy’s Kiddie Korps.” Richard Nixon, narrowly defeated by Kennedy in the 1960 presidential election, called it a “cult of escapism” for young men hoping to avoid the military draft. Dwight Eisenhower, who had preceded Kennedy as president, called it a “juvenile experiment” and suggested volunteers be sent to the moon.

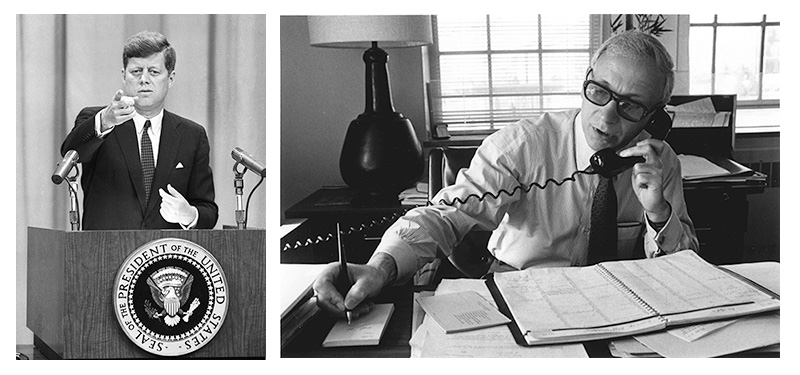

ASK NOT: At a press conference in 1961 (left), President John F. Kennedy outlined the Peace Corps; Donald Hess joined the University’s administration after serving as worldwide Peace Corps director from 1972 to 1974.

ASK NOT: At a press conference in 1961 (left), President John F. Kennedy outlined the Peace Corps; Donald Hess joined the University’s administration after serving as worldwide Peace Corps director from 1972 to 1974.Born of eternal optimism, the Peace Corps has endured challenges. While the program sought to share American skills with people in developing nations, the corps often went to work in countries that had no diplomatic relations with the US government. Volunteers had their own obstacles—living space, weather, language barriers, homesickness, lack of supplies, and threats of injury or death. More than 300 volunteers have died on duty from car crashes, accidents, sickness, drowning, animal attacks, and violent crime.

The organization has faced criticism in recent years over claims of sexual assault alleged by volunteers, many accusing the Peace Corps of putting them in dangerous situations, ignoring their claims, or blaming the volunteers for getting into danger. A USA Today story published this spring reported that 33 percent of volunteers (about 1,280 people) who finished service in 2019 said they experienced sexual assault that ranged from groping to rape. That figure was up from 25 percent in 2015. Following the story, acting Peace Corps director Carol Spahn said in a statement that she was “very sorry for the trauma” volunteers had endured, adding that “these stories demonstrate that we still have work to do to support our volunteers.”

In March 2020 more than 7,000 volunteers were called back to the United States due to the COVID-19 global pandemic. Earlier this year, volunteers were deployed across the US to help administer COVID-19 vaccinations. It was only the second time in history that Peace Corps volunteers had worked within the country’s borders, the first being in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina in 2005.

One of the those called back to the United States was Chiamaka Alozie ’17, a chemical engineering major from Brooklyn, New York. She worked in Panama on a water and sanitation project from July 2018 until her recall in March 2020.

She says her experience has given her a new perspective on how easy it is for American citizens to view the world through a lens of prosperity that’s not available to people in other parts of the world. “It’s made me want to take an active role in not perpetuating the cycles bred from ignorance,” she says.

The Peace Corps received new attention in June, when US Senators Susan Collins (R-ME) and Dianne Feinstein (D-CA) led a bipartisan group calling for “robust funding” for the Peace Corps after several years of no increases.

“As we begin to emerge from the pandemic, a renewed American footprint of Peace Corps volunteers around the world will help our country’s diplomatic efforts and strengthen our country’s relationships around the world,” the senators wrote. “Doing so will ensure that the Peace Corps not only sustains robust programs and services in the face of deteriorating purchasing power but returns to the field with vigor and American spirit, renewing the promise of its creation six decades ago.”

Renewing the spirit of the Peace Corps is important, says Dillon Banerjee, a former Peace Corps volunteer and author of the 2000 book, So You Want to Join the Peace Corps: What to Know Before You Go. His “hope and expectation” is that volunteers soon will be deployed across the globe.

“The Peace Corps is an important and very cost-effective arm of our larger diplomacy machinery,” Banerjee says. “It has a positive ripple effect at home and in the countries where our volunteers serve.”

He acknowledges that the program has changed through the decades to mirror world priorities, such as gender awareness and environmental protection programs.

“Volunteers nowadays often have access to cell phones in even the most remote regions and can access information online, create and maintain blogs, post videos, and solicit grant money for projects,” says Banerjee, acting deputy chief of mission at the US Embassy in Stockholm, Sweden.

“This means volunteers can plan and implement projects in more holistic and directed ways, with input from a wider array of experts. But it also means volunteers stay connected to home, which can make full cultural integration and the ‘Peace Corps experience’ more elusive. There is something to be said about being disconnected and slightly bored for two years. You learn self-reliance.”

Self-reliance was just one of the lessons for Donald Hall, the Robert L. and Mary L. Sproull Dean of the Faculty of Arts, Sciences & Engineering. He served in Rwanda from 1984 to 1986 as a visiting professor, teaching business and technical writing at the National University of Rwanda.

Hall had completed his master’s degree in comparative literature at the University of Illinois before joining the corps, and his volunteer service offered him a chance to see if he wanted to pursue an academic career. An avid hiker who “interacted with the gorillas several times,” he was attacked by a pack of wild dogs his first year, suffered a dislocated shoulder that still troubles him, and endured rabies treatment. The takeaway was worth it.

“I learned resilience, and how to push through immediate difficulties,” he says. “I stayed on the job. When I left the Peace Corps at 26, I was ready to pursue a PhD and well prepared for the career that awaited me.”

Denise Malloy, an assistant professor in the Writing, Speaking, and Argument program, served from 1988 to 1990 in Western Samoa—now Samoa—with future husband Robert Malloy ’00D (Pdc), ’01M (Res).

“I’d been a teacher for six years, so I wasn’t fresh out of college,” Denise says. “We were in graduate school and had been exploring opportunities to teach overseas. We both pulled a Peace Corps post card off the bulletin board the same night and mailed it in.”

The couple lived with host families the first three months, while training and learning the Samoan language. They were then placed in an apartment building with other Peace Corps volunteers—with a mosquito net covering the bed at night—and worked as lecturers at Samoan Teachers College over the next two years.

“It definitely lived up to its advertisement as ‘the toughest job you’ll ever love’ and quite possibly the most unusual way to start a marriage,” Denise Malloy says. “Would I do it again? In a heartbeat.”

Two other professors in the Writing, Speaking, and Argument program are Peace Corps alumni. Rachel O’Donnell taught health, sexuality, and hygiene to youths in Guatemala from 2002 to 2004, and Kate Phillips taught English to middle schoolers in Madagascar from 2006 to 2008.

Glenn Cerosaletti ’91, ’03 (MA)—now assistant dean of students and director of the Center for Community Engagement at the College—helped farmers improve crop production in Bolivia from 1994 to 1996. He worked in a desert-like climate more than 10,000 feet above sea level.

“My motivation for serving was to gain international experience, benefit from language learning, and explore a career in international development,” he says. “I’ve advised many students over the years about applying to the Peace Corps.”

The Peace Corps: For ‘Glass Half-Full People’

Spahn reflected earlier this year on the 60th anniversary and the global pandemic. “I am reminded of how far we have come and what an unprecedented time we are in now,” she said.

“The past 60 years have truly prepared us for this historic moment. During a pandemic that has touched every corner of the globe, it’s clear that we are all in this together. As we look to the next 60 years, I know the Peace Corps will continue to be a community of people—all over the world—willing to do the hard work of promoting peace and friendship.”

Redmond says he’s proud of his service, and those of hundreds within the University community.

“There’s a famous Peace Corps public service announcement that says they’re looking for ‘glass half-full people,’ ” Redmond says. “One of my favorite sayings is, ‘A pessimist sees the glass half empty. The optimist sees the glass half full. The Peace Corps volunteer says, ‘I could take a bath in that.’ ”