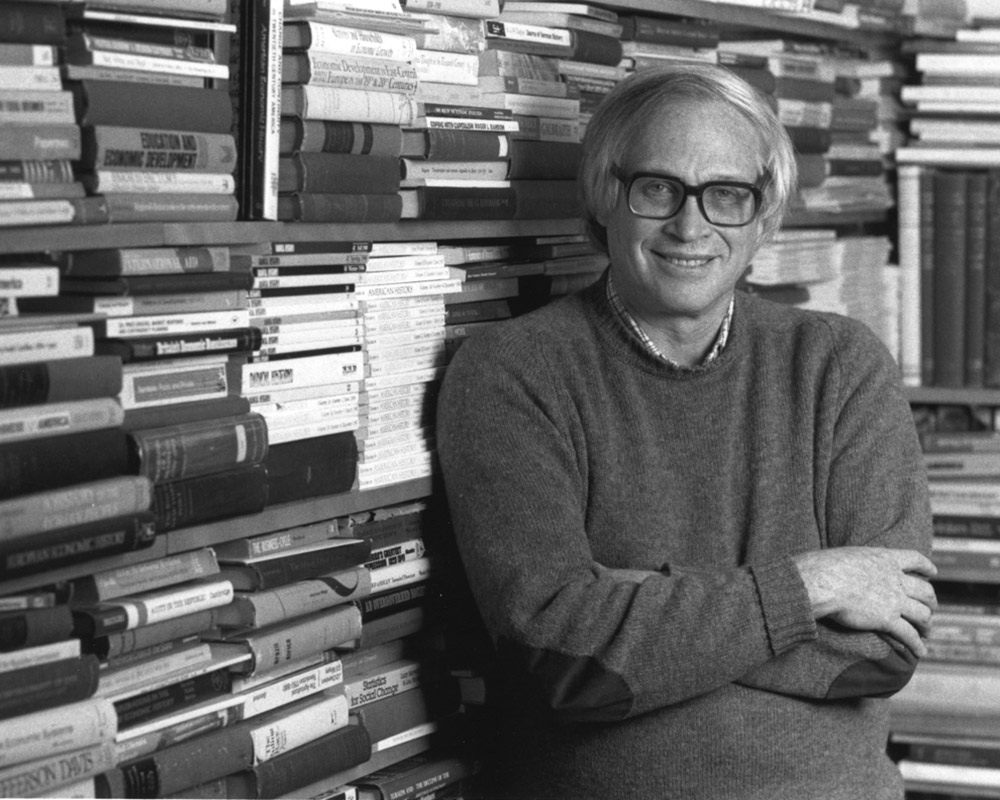

Economic Historian Stanley Engerman

ECONOMIC POWER: “Before we had the internet, we had Stan,” colleagues say of Engerman’s generosity as a scholar and the breadth of his knowledge of economics and economic history. (Photograph: University Libraries/Department of Rare Books, Special Collections, and Perseveration)

ECONOMIC POWER: “Before we had the internet, we had Stan,” colleagues say of Engerman’s generosity as a scholar and the breadth of his knowledge of economics and economic history. (Photograph: University Libraries/Department of Rare Books, Special Collections, and Perseveration)Stanley Engerman, an internationally recognized economic historian, is being remembered as a pioneering scholar, dedicated teacher, and generous colleague.

Engerman, who earned wide praise for his work on the economic impact of institutions, most notably through his study of slavery, died in May.

Claudia Goldin, a professor of economics at Harvard University who worked with Engerman on a 1991 paper, says that one of Engerman’s enduring contributions to the field was his influence on fellow economists.

“If you check the papers that were published in the last 50-plus years, you will see thanks and acknowledgments to Stan in an extremely large number,” says Goldin. “Before we had the internet, we had Stan, and he was incredibly important to everyone.”

Engerman, who would become the John H. Munro Professor of Economics in 1984—a title he held until his retirement in 2017—and a professor of history, joined the Rochester faculty in 1963, shortly after earning his PhD in economics from Johns Hopkins University.

Engerman’s most important work is widely considered to be Time on the Cross: The Economics of American Negro Slavery (Little, Brown and Company, 1974), coauthored with fellow economic historian Robert Fogel, who would go on to receive a Nobel Prize. The book examines the economic underpinnings of American slavery, upending the conventional belief that slavery was not economically viable.

“One point that was destroyed by Time on the Cross was the idea that slaveholders kept slaves for prestige, rather than economic reasons,” says Joseph Inikori, a professor emeritus of history at Rochester who coedited with Engerman the 1992 book The Atlantic Slave Trade: Effects on Economies, Societies and Peoples of Africa, the Americas and Europe (Duke University Press). “Engerman and Fogel made it clear that slavery was a business enterprise centered on economics,” he says.

As the authors explain in their book, “There is no evidence that economic forces alone would have soon brought slavery to an end without the necessity of a war or some other form of political intervention.”

Michael Wolkoff, a professor of economics at Rochester, notes that Engerman was instrumental in the development of cliometrics, the application of econometric techniques to the study of history. In honor of his contributions, the Cliometric Society named Engerman a fellow in 2010, one of many awards and accolades he received during his lifetime.

Engerman’s wife, Judy, died in 2019. He is survived by his three sons—David, Mark, and Jeff—and his sister Natalie Mayrsohn.

—Peter Iglinski ’17 (MA)

This essay is drawn from a longer story.