All the Cameras in Japan

As December rolled around and I started plotting out the end of this year-long series, I had a bunch of ideas for what the final few posts could be about. Knowing that 2019 will bring about some changes to Three Percent (has it ever really remained the same? over eleven-plus years, the one thing that’s remained constant is my desire to write all the swears), I wanted to blow this year out in style. I know that next week I’ll post a post of all my posts (a list of lists! mega-list!) highlighting the ones (one?) that I think are the most interesting. (Seeing all these in one place, with their silly titles and recaps of grump, which is different from grumpy recaps, will either make clear the trajectory I intended for this series, or paint a picture of my fragmented, aging mind. Or both.)

I also know the title for the final post of the year, and the complicated (re: nonsensical) matrix behind it. (I can not wait to work on this.)

Which left one last post (this one!) to try and bring together a bunch of remaining threads from earlier in the year. Looking through my list of potential blog post ideas, nothing really seemed to be appropriate.

- The most obscure books in the translation database from the most obscure presses. (An anti-Book Marks list and I just want to leave everyone alone for the holidays.);

- An update on the sales numbers from all the January translations + lots of math. (Too depressing right now and the graphs all went missing.);

- A look at Lit Hub’s mammoth “best of the best of the best of” list in hopes that it will show that success is usually found by the new (new press, debut author) or the super established—demolition of the middle. (Not very interesting and the list is too long to parse.);

- Five things that would revolutionize the publisher-bookseller relationship. (Way too much work.);

- A summary of the 2018 translation statistics. (Writing that for Publishers Weekly and can expand on it here after the article is published.);

- An analysis of the translators who have had the most work published over the past eleven years and if that’s consistent from one year to the next or a bit random. (SAVE FOR 2019!);

- Prisoner’s Dilemma and Game Theory as it relates to publishing (see Winter Institute) and the desire to defect/compete rather than collaborate. (Again, save for later);

- Fake jacket copy for my ten favorite books of the year, without ever identifying which books those were—a guessing game for the well-read. (Can you be more pretentious?);

- A self-trolling post in which I look at the books I wrote about 10 years ago, and what’s changed in my approach over those years. Like, apparently, a few years back I wrote something called “The Problem with Book Awards [Why America Sucks, Part Infinity]”? I’m sure that’s a 100% rational post. (THIS SERIES IS ALREADY TOO SELF-INDULGENT.).

Since these all sucked/were too much work, and since I had declared publicly (aka on a podcast) that the rest of my December was going to be reading for fun (lie!), I thought I’d read The Lady Killer by Masako Togawa and build some sort of post around that.

The Lady Killer by Masako Togawa, translated from the Japanese by Simon Grove (Pushkin Vertigo)

Last week I talked a bit about the sexiness of Coach House’s paper. Well. Pushkin Vertigo is the exact opposite, and yet I find the precarious production values in these books to be incredibly appealing. It’s such a weird tradition for British presses to produce such ephemeral products. (Books that go the way of the British Empire, but in months, instead of centuries! Not funny, I know. But, maybe, kind of funny.) As I was reading this, I kept waiting for chunks of pages to simply fall out, or for the pages to instantly yellow in the sun—and there was something fittingly pulpy about all of that. All these Pushkin Vertigo books are designed in the same disposable way, and I think I love it.

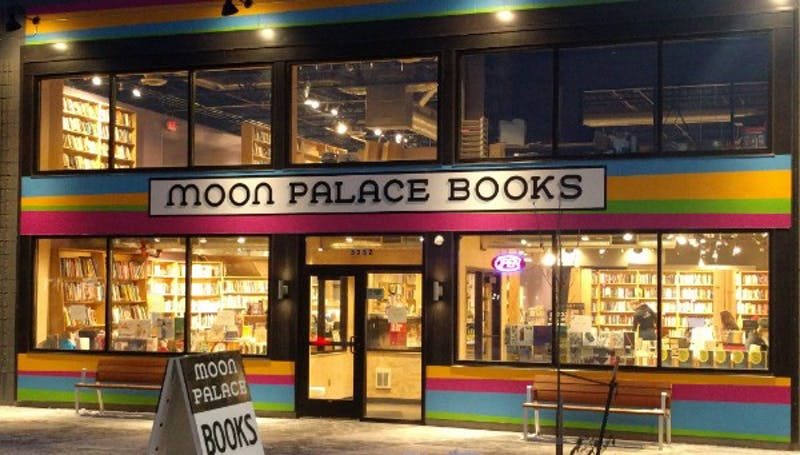

In terms of this particular title, it’s written by a cabaret performer turned mystery writer who passed away a couple years ago and is considered to be one of Japan’s greatest crime writers. She has one other book in this series—The Master Key—which won a prestigious award, and which I’m planning on buying from Moon Palace Books next week.

Quick digression: LOOK AT THIS FUCKING PALACE

What you can’t see is the cafe/bar in the back AND the performance space where Consortium held its sales conference party and where old punks rock the fuck out most every night. This is my Shangri-La and I want one here in Rochester.

Anyway, the plot of The Lady Killer: A dude who physically can’t have sex with his wife, but can totally get down with random women he seduces at bars, gets one of his “conquests” pregnant. Six months later, she kills herself, in part because she’s pregnant with his child. Shortly after that, the women he’s with—all detailed in sterile, offensive ways in his “hunter’s diary,” which, yes, is maybe the worst thing—start turning up dead. He’s convicted because his rare blood type is found at every scene along with matching semen. But a lawyer thinks it’s all a frame-up. (That’s British-speak, I believe.) He and his employee start investigating, and the mystery unfolds bit by bit to a somewhat surprising ending.

(I have no idea how to judge the “surprisingness” of a twist ending in a crime novel. I don’t read enough of them to have a baseline for what’s “normal” and “expected.” But in the crime novels I have read—small sample size!—they all end with a bit of a twist, which, because I’m generally waiting for a twist, makes the twist not all that twisty. Is there a game theory to writing mysteries? What I mean is, do you get added benefit—more dedicated readers—by having one out of every five books end the way everyone expected it? But would that mean that it would end with the most obvious twist? Or could you start a mystery novel by declaring the main suspect on page one and then again in the final paragraph, with absolutely zero doubt in the middle as to that character’s guilt? Didn’t see that one coming! She played it straight!)

Initially, I thought The Lady Killer was making it into English for the first time ever, but the Human Bibliography of International Fiction, Michael Orthofer, set me straight about this being a reprint. (Weird that Publishers Weekly reviewed it, but not as weird as Kirkus putting Toddler-Hunting and Other Stories on their “Best of 2018” list—a book they originally reviewed in 1996.) Which short-circuited my idea of making this the focus of a post, since the initial premise was to read 52 new translations over 2018 and write about one each week.

Not a recommended course of action. Just as there are only about 50-75 “great” bookstores in America, there are only ever about 25-30 “great” translations to come out in a year. And the more one ages, the less time one wants to spend reading something they just don’t care about. Which brings us to . . .

Seventeen by Hideo Yokoyama, translated from the Japanese by Louise Heal Kawai (FSG)

I tried to read Yokoyama’s earlier book, Six Four, but couldn’t get into it. It seemed interesting enough, but there are soooooo many words on every page that don’t really need to be there. A good book doesn’t need to describe everything. My sense—and this is unfair given that I read about 60 pages of a 9 million page novel—is that his prose doesn’t leave enough space for the reader to imagine anything. And the best reading experiences are only half-directed, with the other half being supplied by the reader.

Seventeen is a book about journalism and a plane crash. That’s cool! And the prose is as workmanlike as can be. It’s as if it were 350 pages of a craft seminar on declarative simplicity.

There was nothing to do but wait. The layout of the city news pages had been completed. It consisted entirely of the Kyodo articles Nozawa had been working on. The moment they received Sayama’s draft, they would switch it around. The plan was in place, but still the phone didn’t ring. Time was steadily creeping up on Yuuki.

Anxiety was stalking him, too. Since night had fallen, there had been one piece of bad news after the other.

I know this isn’t a term, but this is what I think of as “lock-step writing.” A and then B which follows A and both are standard, logical events that progress in ways that everyone can imagine.

Honestly: Why do people like books like this?

Don’t get me wrong, it’s not a shitty book or anything—it’s just utterly forgettable from a style standpoint.

Why do people like books that lack style?

These are the same people who complain that are books are “too demanding” and don’t have “easy to pitch plots.”

Yeah! I know! What are books?

*

I gave up on Seventeen. I only have so many more days to live, books to read. And, so far, I’ve finished 101 books this year. Not particularly impressive, but I hit my goal. (And will likely finish a few more before 2019.)

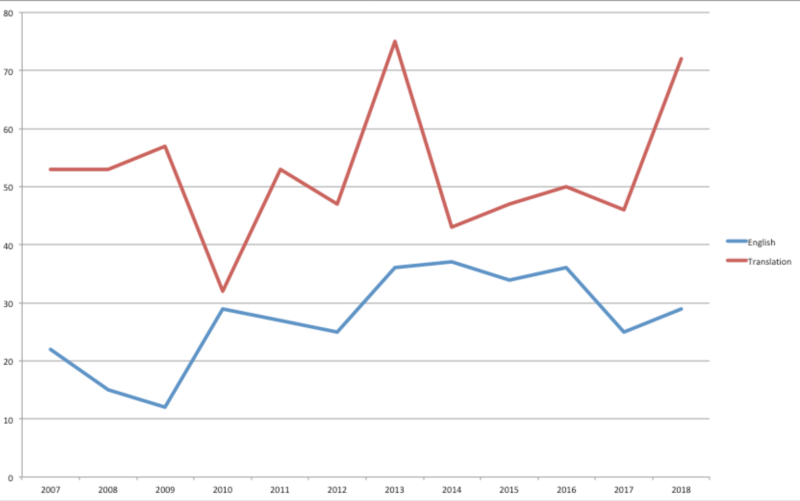

Because I’m an über-nerd who is a little too into Excel spreadsheets, I have a list of every book I’ve read (or read part of) going back to 2007. Not only that—I have them categorized by author’s country of origin and language. And whether they were written by a man or a woman. I was Goodreads before Goodreads was LibraryThing. (NERD JOKE ALERT.) Yes, you’re right, junior high wasn’t very fun . . .

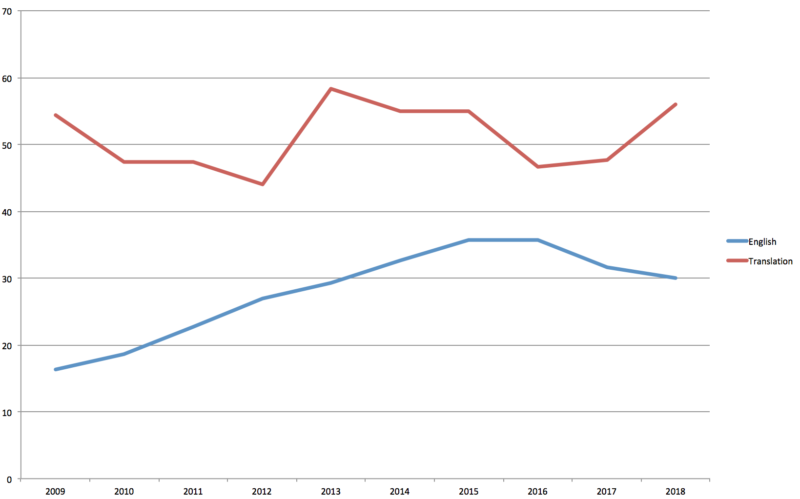

The funniest thing about that chart of how many books I read that were in translation vs. originally written in English is that it perfectly captures why I like rolling-average charts better than single-year ones. Look at 2010. In isolation, it looks rather dramatic. But, if you take into account the three-year average for both lines (e.g., total titles 2007-2009/3 = 2009 number, 2008-2010/3 = 2010 number, etc.), things get a bit smoother:

Quantifying your interior life is a very weird thing to do.

*

What I’ve never tracked is the books I’ve read by region.

When I was at Quail Ridge Books, in the time just before Y2K ruined the world, I organized an “International Literature” section. This is a controversial move today—”why separate translations? A good book is a good book is a good book. Don’t put international lit in a ghetto!”—but in 1999, there was almost zero attention being paid to international literature, and putting these titles in with the regular fiction didn’t normalize their existence, but rather masked them so that you could grab Charles Frazier’s Cold Mountain while not even seeing Carlos Fuentes’s Terra Nostra.

(Another post idea: Irrationality and Perceptual Bias in a Bookstore Setting. Sounds academic. Maybe I could finally get an advanced degree by writing . . . no. Never going to happen. At this point I feel like it’s a badge of honor to not have an MA or PhD or whatever. I always wanted to have one . . . to be in academia, but I’m too far gone now. I’m stationed in a part of the world in which business and culture fight and fuck and advanced degrees don’t matter as much as sales trends and the cult of personality. Besides, if I ever have to write like an academic again, I may lose the last remaining sliver of my dignity.)

After getting permission from my bosses to make this section—have I written this before? Is everything just a rewrite of a rewrite done in an insomniac fog? Just wait till you read The Dreamed Part and that reference will land—I figured out that I absolutely had to group things into regions instead of countries. Which is, inherently, fraught. To what region do you file Turkey? Algeria? Morocco? Turkistan?

I did what I thought made sense, and committed to revising the groupings every time someone brought up a thought-out complaint. This happened once or twice, which is a long way of saying: These charts are inherently fucked. I know that. I’m just trying to cull something interesting from the Translation Database (still down!) that might signify something.

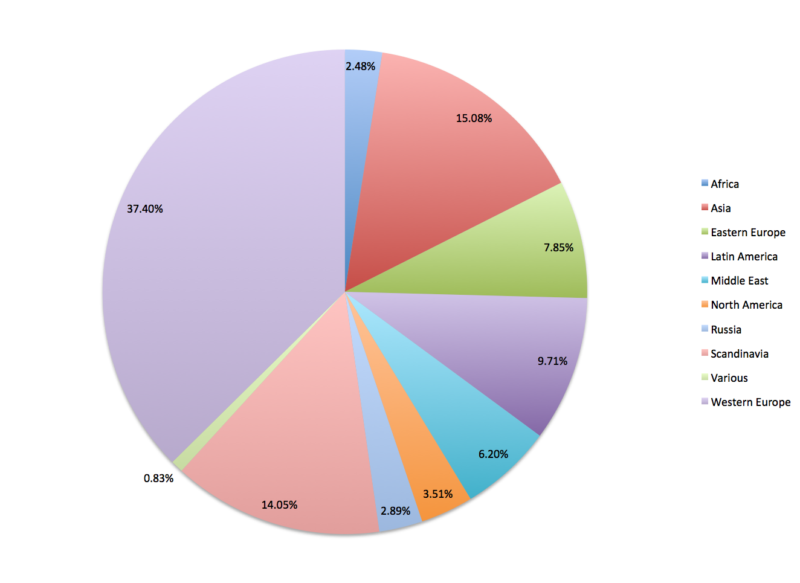

Here’s a chart of 2018 fiction broken down by arbitrary regions.

Unsurprisingly, Western Europe (Italy + Spain + Germany + France + you get the picture) dominated, with 37.40% of all fiction translations published. But, then, Asia! You know what? Because Rachel Cordasco is a fanatic about finding translated Japanese books. No offense of anyone, but these Japanese “light novels”? Holy crap are there a LOT of them. And each one sounds more insane and like YA-bullshit than the last.

The human realm of the kingdom is headed for its greatest disaster yet! After failing to prevent a daring raid on the Eight Fingers’ appalling brothel, the Six Arms are dying for a chance to defend their reputation as the criminal underworld’s strongest enforcers. These criminals are notorious for their brutality as much as their strength, meaning the only people who stand a chance against them are the legendary Blue Roses . . . and one polite, dignified butler. When these thugs make Sebas the first target of their revenge, they may get much more than they bargained for by inadvertently picking a fight with Ainz Ooal Gown!

OK, cool. Appalling brothels, enforcers, Blue Roses, Ainz Ooal Gown—GOT IT.

This is, quite literally, the description to Overlord, Vol. 6: The Men of the Kingdom Part II.

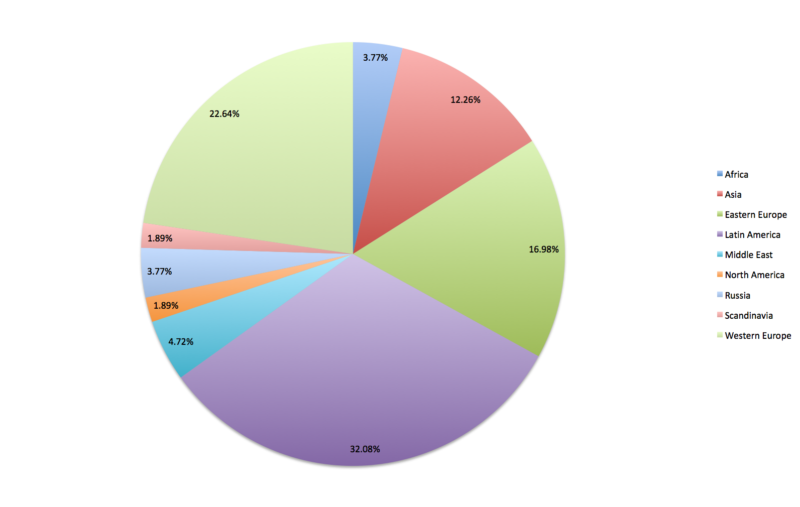

How does this measure up against the poetry published in 2018?

Well, that’s different. (Read that with a Minnesotan accent.) In terms of poetry, Latin America dominates. That’s a strong 32+% for poets mostly from Argentina, Chile, and Mexico.

Well, that’s different. (Read that with a Minnesotan accent.) In terms of poetry, Latin America dominates. That’s a strong 32+% for poets mostly from Argentina, Chile, and Mexico.

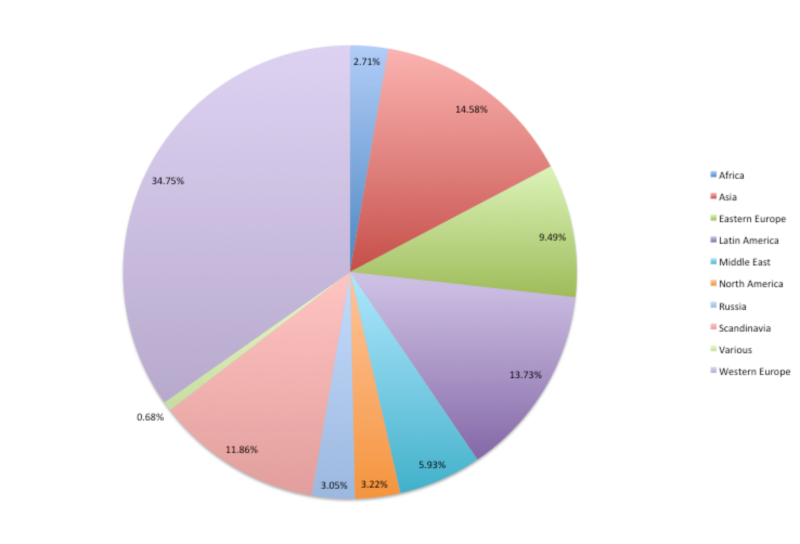

Put all the numbers together and you get this:

Western Europe is above Asia which is above Latin America which is above Scandinavia . . . This totally tracks. French/German/Spanish always dominate, although there are some indications that this stranglehold isn’t going to last forever.

And, from a value exploitation/game theory/Moneyball perspective, there’s a shitload of value to be found by honing in on the regions at the lower end of this chart. Africa and the Middle East, obviously, but also Russia and Eastern Europe.

*

You know what would make all my research much more interesting and valuable? Access to Nielsen BookScan. As flawed as it might be at capturing total sales, it’s incredibly useful for correlating production and sales. I could do sooooo much if someone would just give me a password. (Spoiler Alert: Nielsen denied me. And Consortium/Ingram only gives us info on our own books.) I feel like I’m being denied my intellectual freedom . . . or, whatever. If I had a PhD in data science they’d probably give me access . . .

*

The first person to email or text me with the lyric following the title of this post will get a collection of a few of my favorite books. (Which is super easy, since the title of the post is also the title of the song. And “the best play in American football” is not right.)

*

So here’s the thing: I need to leave this series behind; I want to do something new; I don’t want to lose these nights of writing in this particular voice. (I’ve said it before, but writing these posts is like some sort of performative therapy. If I lost this, I might lose myself.)

Reading two Japanese books in a row reminded me of a weird/nerdy thing I did back in college: On every winter/summer break, I would read a bunch of books each month that fit within a particular grouping. “Books by Women.” “Science Fiction.” “Latin American Classics.” And as forced and silly as that was? I liked it. I made connections that were maybe there, maybe not. I spent too much time with card catalogs trying to learn about particular pairs of authors that were likely as random as they were intertwined.

That’s what 2019 is going to be. A return to reading as exploration.

If 2018 was a way of evaluating the cultural side of the publishing world through new translations, 2019 will be about exploring sets of books, as books, from a reader’s perspective.

Here’s what you can expect:

- January is going to focus on Spain. I’ll write an intro post with shittons of stats about books from Spain. And will follow that with weekly rambles about Spanish books translated from Castilian, Galician, Basque, and Catalan;

- Several interviews a month with translators—established and up-and-coming, but mostly the latter;

- Months in which I try and focus on publishers doing work from a region (like all the Quebecois publishers) and months in which I take a new book and try and work backward (chronologically) through its influences;

- More samples, because I want to promo our forthcoming titles and give translators a space to share passion projects;

- A monthly “What You Missed” post to counter all the “You Must Read X in Y!” posts that already exist. This will include translation stats and highlights of books that weren’t necessarily “trendy”;

- Every month we’ll feature a backlist Open Letter author and offer a discount on their title(s). These selections will only sometimes be synergistic with all that’s listed above . . .

I don’t know that I’ll actually follow through on all the posts already plotted out for January, but, then again, I didn’t plan to finish this series on “A Year of Reading New Translations” (I’m nothing if not a quitter), but I’m two posts away and feeling nostalgic.

Hug your loved ones over the holidays, and come back next week for a highlight reel, and on 12/30 for “10 x 10 x 10: Everything Comes to an End.”

Leave a Reply