Interview with Amaia Gabantxo

To finish off this month of Spanish literature, I talked to Amaia Gabantxo, translator of Twist and Blade of Light by Harkaitz Cano along with a half-dozen other Basque authors, including Bernardo Atxaga, Unai Elorriaga, and Kirmen Uribe, among others. She also moonlights as a flamenco singer and recently released an album.

Chad W. Post: Let’s start off simple: could you tell us a bit about yourself and how you became a Basque translator?

Amaia Gabantxo: Thinking back, it all seems like a serendipitous confluence of events. I grew up bilingual in the Basque country, with Basque as my mother tongue and Spanish as the language of my initial schooling. Only by the time I reached high school age was I able to receive an education in Basque—before that, 40 years of Franco’s dictatorship had forbidden the use of the language. So I did my primary schooling in Spanish and my secondary schooling in Basque. I had a gift for languages in any case; I was pretty fluent in English, and I could get by in French pretty well despite never having received any French lessons. After high school, hoping to enroll in the School of Translators of Granada and in preparation for my entrance exam, I went to Northern Ireland to spend 9 months there perfecting my English. I stayed in a fishing village on the Antrim coast, next to one of three Ulster University campuses, with relatives of friends.

Amaia Gabantxo: Thinking back, it all seems like a serendipitous confluence of events. I grew up bilingual in the Basque country, with Basque as my mother tongue and Spanish as the language of my initial schooling. Only by the time I reached high school age was I able to receive an education in Basque—before that, 40 years of Franco’s dictatorship had forbidden the use of the language. So I did my primary schooling in Spanish and my secondary schooling in Basque. I had a gift for languages in any case; I was pretty fluent in English, and I could get by in French pretty well despite never having received any French lessons. After high school, hoping to enroll in the School of Translators of Granada and in preparation for my entrance exam, I went to Northern Ireland to spend 9 months there perfecting my English. I stayed in a fishing village on the Antrim coast, next to one of three Ulster University campuses, with relatives of friends.

Luckily for me, an eagle-eyed and very well informed EFL teacher (I wish I could remember his name) let me know that the European Union had set aside scholarship money for European students wishing to attend university in member states other than the ones they were born in. He knew I was attending his “English Proficiency” class because I needed to pass a Cambridge exam of the same name to be considered for entry at the School of Translators of Granada and after class one day he put a question to me: if I really wanted to be a translator, wouldn’t it be better for me to study in the UK? If I went back to Spain, he said, my English would inevitably decline.

He provided all the paperwork and phone numbers (this was in the days before the internet) I needed to process my application. It took a lot of frustrating phonecalls, as this was something very, very few people were doing in those days. But my hosts, the Fordes, especially Maureen, were incredibly helpful and determined to get me there. Most of the administrators we contacted weren’t aware of the EU scholarships and had no idea about the process required to get me into the admissions system. Frankly, I’m not quite sure how it all happened. I suspect Maureen’s tireless persistence and charming telephone manner had a lot to do with it. But happen it miraculously did, and I got a place at Ulster University to study English and Irish literature, and a scholarship to go with it. I also passed the entry exam and got accepted in Granada, but I decided to take my place in Northern Ireland—where I was, I’ll add, the only foreigner in my class.

So I happily studied English and Irish literature at Ulster University, and for my final year thesis I wrote a comparative analysis on the narratives of conflict in the works of Northern Irish author Bernard McLaverty and Basque author Bernardo Atxaga. In the process of writing, I found myself repeatedly focusing on the fact that Atxaga’s books were translated from the Spanish translations of the original texts, and not from Basque (this, I’ll confess, annoyed me). So much so, that at one point my thesis supervisor, Dr. Robert Welch, commented that perhaps I should start translating literature directly from Basque into English, since no one else seemed to be doing it and I was perfectly placed to take on the job.

So I happily studied English and Irish literature at Ulster University, and for my final year thesis I wrote a comparative analysis on the narratives of conflict in the works of Northern Irish author Bernard McLaverty and Basque author Bernardo Atxaga. In the process of writing, I found myself repeatedly focusing on the fact that Atxaga’s books were translated from the Spanish translations of the original texts, and not from Basque (this, I’ll confess, annoyed me). So much so, that at one point my thesis supervisor, Dr. Robert Welch, commented that perhaps I should start translating literature directly from Basque into English, since no one else seemed to be doing it and I was perfectly placed to take on the job.

And that was it. Once he planted the idea in my brain, it seemed so obvious. It became clear to me that everything I’d done until then led to the realm of literary translation. I had even started writing my own fiction and poetry in English at that point, the language switch had happened naturally. So I enquired, and found out about the famous Master in Literary Translation at the University of East Anglia, home to the British Centre for Literary Translation—which had been founded by W.G. Sebald, who taught there and was one of my literary heroes. I applied, got in, and my world bloomed like a flower in the springtime: I started publishing translations of Basque poetry while still doing the MA; astonishingly, I was invited to read the Dublin Writers Festival. Short stories followed, and soon thereafter my first commission for a novel. I haven’t stopped translating Basque literature since.

CWP: Are there any distinctive elements to contemporary Basque writing?

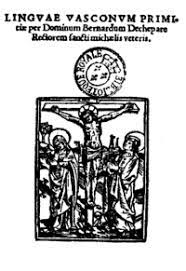

AG: I always say that the case of Basque literature is a paradoxical one. Written in (possibly) the oldest language in Europe, it is simultaneously (also possibly) the youngest literary system in Europe. Basque writers don’t have many forebears to emulate or a “tradition” to write into: the first Basque book, Bernart Etxepare’s Linguae Vasconum Primitiae, was published in 1545, and from then until the early twentieth century most of what was written was church-related (translations of sections of the Bible, prayer books . . . ). Contemporary Basque writers are creating, right now, a tradition that future Basque writers will be able to lean on. So, if there’s one distinctive element to Basque literature today, perhaps it’s that Basque writers feel that EVERYTHING needs to be written, that there’s room for EVERYTHING. Another consequence of writing into such a tradition-lacking literary tradition is that precisely because there are no blueprints, writers feel very free about what they can write and, as a result, there is a lot of experimentation.

AG: I always say that the case of Basque literature is a paradoxical one. Written in (possibly) the oldest language in Europe, it is simultaneously (also possibly) the youngest literary system in Europe. Basque writers don’t have many forebears to emulate or a “tradition” to write into: the first Basque book, Bernart Etxepare’s Linguae Vasconum Primitiae, was published in 1545, and from then until the early twentieth century most of what was written was church-related (translations of sections of the Bible, prayer books . . . ). Contemporary Basque writers are creating, right now, a tradition that future Basque writers will be able to lean on. So, if there’s one distinctive element to Basque literature today, perhaps it’s that Basque writers feel that EVERYTHING needs to be written, that there’s room for EVERYTHING. Another consequence of writing into such a tradition-lacking literary tradition is that precisely because there are no blueprints, writers feel very free about what they can write and, as a result, there is a lot of experimentation.

CWP: It’s possible that Bernardo Atxaga is the most famous Basque writer among English-readers, yet most of his books have been translated into English via the Spanish translation of the original. Do you/other Basque scholars consider this at all problematic? (Not to diminish MJC’s translations—she’s excellent!)

AG: As you will have read above, this is one of the reasons that motivated me to translate directly from Basque into English. I agree that MJC is a terrific translator, and I know that author and translator relationships can be profound, and think that Atxaga and Jull Costa are very close and wouldn’t want to impinge on that. When they started collaborating in the late 90s there was no other way to translate Basque literature but to do it through a bridge language. I don’t know if other scholars pay much attention to this, but it is something I wrote about at length in a recent review I wrote for the TLS (of Atxaga’s Nevada Days, translated by MJC), since I do believe that Atxaga’s work should be translated from Basque now that it’s possible. Apart from anything else, his books are actually very different in tone and style in their Basque and in Spanish versions. Sadly, the fact that Atxaga still gets translated from the Spanish versions of his books is part of an established system of oppression, colonization, and appropriation of Basque culture that’s bigger and older than all of us. I have no doubt that everyone involved in the case of Atxaga’s translations into English (MJC, his publishers, Atxaga himself) are super-nice, cool people, but the system to which they continue to contribute remains problematic. There are three or four people translating Basque literature into English right now, and any of us could translate Atxaga directly. (I would love to do it, of course, although I suspect that writing this here probably reduces the chances that I will).

AG: As you will have read above, this is one of the reasons that motivated me to translate directly from Basque into English. I agree that MJC is a terrific translator, and I know that author and translator relationships can be profound, and think that Atxaga and Jull Costa are very close and wouldn’t want to impinge on that. When they started collaborating in the late 90s there was no other way to translate Basque literature but to do it through a bridge language. I don’t know if other scholars pay much attention to this, but it is something I wrote about at length in a recent review I wrote for the TLS (of Atxaga’s Nevada Days, translated by MJC), since I do believe that Atxaga’s work should be translated from Basque now that it’s possible. Apart from anything else, his books are actually very different in tone and style in their Basque and in Spanish versions. Sadly, the fact that Atxaga still gets translated from the Spanish versions of his books is part of an established system of oppression, colonization, and appropriation of Basque culture that’s bigger and older than all of us. I have no doubt that everyone involved in the case of Atxaga’s translations into English (MJC, his publishers, Atxaga himself) are super-nice, cool people, but the system to which they continue to contribute remains problematic. There are three or four people translating Basque literature into English right now, and any of us could translate Atxaga directly. (I would love to do it, of course, although I suspect that writing this here probably reduces the chances that I will).

CWP: Which other classic Basque authors should English readers know about?

AG: The Basque Series, curated by the Center for Basque studies at the University of Nevada Press has put together a collection of “classics.” We slowly keep contributing volumes to it, and anyone interested on the subject of Basque literature could start there. The first Basque book, Linguae Vasconum Primitiae, is on their list. It’s a collection of 16 poems written by a monk, Bernart Etxepare, in 1545. The UNP has also published a couple of anthologies of short stories, which can give you an overview of authors currently writing in Basque (An Anthology of Basque Short Stories and Our Wars). My recent translation of Gabriel Aresti’s two poetry collections, Downhill and Rock & Core are also part of that collection. Aresti is regarded as the “father of modern Basque poetry,” and was the first to write poetry in vernacular Basque—until then, most Basque poetry had been written in a high-flown literary language that borrowed heavily from the stylistic quirks of ecclesiastical writings.

Ramon Saizarbitoria’s Rossetti’s Obsession (translated by Maddalen Saizarbitoria), Lourdes Oñederra’s And the Serpent Said to the Woman and Arantza Urretabizkaia’s The Red Notebook (both translated by Kirstin Addis) are on that list too. As is Anjel Lertxundi’s Perfect Happiness, which I translated. Lertxundi is an author I’d really like to translate more of: Perfect Happiness is a great short novel about a teenage pianist who witnesses an ETA assassination, but I don’t think it’s his best work; he has bigger, more ambitious and thrilling works that need translating, like Azkenaz beste (the story of a Basque wandering Jew) or Otto Pette—both of these books seek to place the Basque storytelling tradition in the bigger context of the European tradition, finding their links and points of conversion. The brilliant Archipelago Books has also brought out two Basque novels I’ve translated: Unai Elorriaga’s Plants Don’t Drink Coffee, a quirky little book told from the perspective of a 5 year-old boy who wants to catch a dragonfly that will make him the most intelligent person in the world, and Harkaitz Cano’s Twist, which is a fantastic novel about the Lasa and Zabala case—a real case about two disappeared young ETA sympathizers whose remains were found ten years after their disappearance. Their families brought a case against the government that caused the collapse of the socialist government in the 1990s. Cano changes the names of all the characters to tell the story, but anyone in the Basque Country or Spain knows exactly what he’s writing about. It’s a key case in recent Spanish history. I also did Cano’s Blade of Light, an absolutely brilliant novella that imagines Hitler won WWII and conquered Manhattan, for the UNP, and Archipelago has just commissioned me to translate Elorriaga’s Ihazko hezurrak, which I’m provisionally calling Last Year’s Bones, a novel that draws parallels between different histories of horror and oppression all over the world. A hard book, but a necessary book.

Ramon Saizarbitoria’s Rossetti’s Obsession (translated by Maddalen Saizarbitoria), Lourdes Oñederra’s And the Serpent Said to the Woman and Arantza Urretabizkaia’s The Red Notebook (both translated by Kirstin Addis) are on that list too. As is Anjel Lertxundi’s Perfect Happiness, which I translated. Lertxundi is an author I’d really like to translate more of: Perfect Happiness is a great short novel about a teenage pianist who witnesses an ETA assassination, but I don’t think it’s his best work; he has bigger, more ambitious and thrilling works that need translating, like Azkenaz beste (the story of a Basque wandering Jew) or Otto Pette—both of these books seek to place the Basque storytelling tradition in the bigger context of the European tradition, finding their links and points of conversion. The brilliant Archipelago Books has also brought out two Basque novels I’ve translated: Unai Elorriaga’s Plants Don’t Drink Coffee, a quirky little book told from the perspective of a 5 year-old boy who wants to catch a dragonfly that will make him the most intelligent person in the world, and Harkaitz Cano’s Twist, which is a fantastic novel about the Lasa and Zabala case—a real case about two disappeared young ETA sympathizers whose remains were found ten years after their disappearance. Their families brought a case against the government that caused the collapse of the socialist government in the 1990s. Cano changes the names of all the characters to tell the story, but anyone in the Basque Country or Spain knows exactly what he’s writing about. It’s a key case in recent Spanish history. I also did Cano’s Blade of Light, an absolutely brilliant novella that imagines Hitler won WWII and conquered Manhattan, for the UNP, and Archipelago has just commissioned me to translate Elorriaga’s Ihazko hezurrak, which I’m provisionally calling Last Year’s Bones, a novel that draws parallels between different histories of horror and oppression all over the world. A hard book, but a necessary book.

Joseba Sarrionaindia is another great author, poet and essayist—accused of terrorism crimes and of being a member of ETA, he was jailed in 1980 and epically escaped prison in 1985 inside a speaker after a concert, and has lived in exile in Cuba since. I’ve translated his poetry for the anthology 6 Basque Poets and for an issue of Words Without Borders, but there’s a novel of his I’d like to translate, Lagun izoztua (My Frozen Friend), and I think we should also have a collection of his poetry in translation, as well as a collection of his essays, because he truly is a fantastic poet and enormously significant Basque writer. Likewise, we need to have a volume of Bernardo Atxaga’s selected poetry in translation—I’ve translated quite a few of his poems and pitched the idea of an anthology to a few places, but although all publishers seem love the poems (they are brilliant), they end up saying no, perhaps because Atxaga is perceived purely as a novelist in the Anglo world. Another great poet and novelist is Miren Agur Meabe, whose lyrical auto-fictional novel A Glass Eye I translated for Parthian in the UK recently (it’ll be released in the US in March). I would also love to do a volume of her selected poems—you can read some of her work in 6 Basque Poets, in Words Without Borders and Tupelo Quarterly. Parthian have also published Karmele Jaio’s My Mother’s Hands, translated by Kirstin Addis, an important contribution to our growing collection of titles in translation. And Hispabooks last year brought out Saizarbitoria’s gigantic Martutene, translated by Aritz Branton (I reviewed it for the TLS last year).

Joseba Sarrionaindia is another great author, poet and essayist—accused of terrorism crimes and of being a member of ETA, he was jailed in 1980 and epically escaped prison in 1985 inside a speaker after a concert, and has lived in exile in Cuba since. I’ve translated his poetry for the anthology 6 Basque Poets and for an issue of Words Without Borders, but there’s a novel of his I’d like to translate, Lagun izoztua (My Frozen Friend), and I think we should also have a collection of his poetry in translation, as well as a collection of his essays, because he truly is a fantastic poet and enormously significant Basque writer. Likewise, we need to have a volume of Bernardo Atxaga’s selected poetry in translation—I’ve translated quite a few of his poems and pitched the idea of an anthology to a few places, but although all publishers seem love the poems (they are brilliant), they end up saying no, perhaps because Atxaga is perceived purely as a novelist in the Anglo world. Another great poet and novelist is Miren Agur Meabe, whose lyrical auto-fictional novel A Glass Eye I translated for Parthian in the UK recently (it’ll be released in the US in March). I would also love to do a volume of her selected poems—you can read some of her work in 6 Basque Poets, in Words Without Borders and Tupelo Quarterly. Parthian have also published Karmele Jaio’s My Mother’s Hands, translated by Kirstin Addis, an important contribution to our growing collection of titles in translation. And Hispabooks last year brought out Saizarbitoria’s gigantic Martutene, translated by Aritz Branton (I reviewed it for the TLS last year).

Another fantastic Basque author is Kirmen Uribe. Whose poetry collection Meanwhile Hold my Hand was published in the US by Graywolf Press and whose novel Bilbao-NY-Bilbao was published by Seren in the UK (both translated by Elizabeth Macklin). Uribe is a master of auto-fiction hybrid memoir-historic novels. He’s currently a Cullman Fellow at the NYPL.

The authors I mention above give you an overview of what’s available and what we could do to round up that particular picture. But there are many more authors who still need translating. Female writers above all. Like all literary systems, the Basque one has been male-dominated since its inception, and that tendency has traveled to the translation realm. At this point, I’m really looking forward to redressing the balance in my translation work and bringing more work by female and diverse authors to English-language publishers.

CWP: In terms of Cano, how did you come to his works? How would you pitch him to an American audience?

AG: I knew Cano’s work because we’re of the same generation, and he started publishing at 19—so for a bookworm like me he was impossible to avoid. He was always on my radar, as far as I can remember, years before I did the MA. He started writing poetry (he is a great poet—read Life with a Tiger in Words Without Borders, a poem about being a Basque and living with the ETA) and it was very obvious from the start that he was a standout author. His technique and perceptive powers were always well ahead of his years.

I translated several of his poems from the collection There’s Someone on the Fire Escape and short fiction pieces from Breakfast on the Piano during the MA—both collections contained very quirky pieces about the year he spent in NY, writing for a Basque newspaper—and was itching to do some more . . . so when I was asked to do Blade of Light for the UNP I was ecstatic. I think he’s a very special writer, a writer’s writer. I find his work thrillingly good—clever, unexpected, layered. Just so, so good. Reviewers in the Spanish press have compared him to Bolaño, and I perfectly understand why they say that. They hit the same spots. I so want the Anglo world to discover him!

He’s someone who takes an askew perspective on the world. Twist, for example, starts with a set of bones that wake up disoriented in their shallow grave. In Blade of Light, he puts Hitler and Charles Chaplin together aboard a ship bound to America. I also translated BSO, a book he wrote in collaboration with Chef Aduriz of restaurant Mugaritz fame. He wrote a set of pieces to go with a set of Aduriz’s recipes. He’s written a book in collaboration with a pianist who played Chopin etudes throughout his writing process. He’s right now finishing a memoir-novel about the fascinating and controversial Basque singer Imanol (the musician inside whose speakers Sarrionandia escaped from prison). Imanol was an activist musician, singing in Basque when it was forbidden to do so, publishing albums under a pseudonym, who was jailed for his activism and had to live in exile, and who, after he returned to the Basque Country following Franco’s death, had to exile himself again to escape ETA’s threats because he spoke against them. Not an easy subject for Basque people, Imanol. I can’t wait to translate the book.

He’s someone who takes an askew perspective on the world. Twist, for example, starts with a set of bones that wake up disoriented in their shallow grave. In Blade of Light, he puts Hitler and Charles Chaplin together aboard a ship bound to America. I also translated BSO, a book he wrote in collaboration with Chef Aduriz of restaurant Mugaritz fame. He wrote a set of pieces to go with a set of Aduriz’s recipes. He’s written a book in collaboration with a pianist who played Chopin etudes throughout his writing process. He’s right now finishing a memoir-novel about the fascinating and controversial Basque singer Imanol (the musician inside whose speakers Sarrionandia escaped from prison). Imanol was an activist musician, singing in Basque when it was forbidden to do so, publishing albums under a pseudonym, who was jailed for his activism and had to live in exile, and who, after he returned to the Basque Country following Franco’s death, had to exile himself again to escape ETA’s threats because he spoke against them. Not an easy subject for Basque people, Imanol. I can’t wait to translate the book.

So I would say that, in essence, Harkaitz Cano is an author that never takes an easy path, a comfortable position. The roundedness of characters can make you gasp . . . now with admiration, now with despair (I’ve wanted to kill a few of them, they’ve disappointed me so . . . having forgotten they were characters in a book). He truly knows how to reveal the fullness of the human condition: the hero and the lowlife in all of us. It’s thrilling because you never really know what direction his books are going to take. He always takes you on ride. I find his books utterly unputdownable.

CWP: What are some of the joys and challenges to translating Twist and Blade of Light?

AG: Translating Blade of Light . . . was fun from the start. There’s a whole section at the start of the book that’s a fragment of an interview with Charles Chaplin published in the San Francisco Chronicle. I went half mad looking for the original. I was living in Brooklyn while translating Blade of Light, traveling to Manhattan every day to spend most of the day in the NYPL with the novel, and I searched and searched for the Chaplin interview . . . the internet offered zero returns, the microfilm section, nothing. I even asked staff in the NYPL to get in touch with the San Francisco Public Library, which they very solicitously did. I wrote to the San Francisco Chronicle (they didn’t answer). The damned interview was nowhere to be found. I’m stubborn and rather enjoy the detective work that comes with literary translation; I like to solve the puzzles it so often poses on my own, so I held off asking Harkaitz where he got the interview from, until I had exhausted all my options. And then I had to. And he answered. He had made it up.

Then there was the issue of the title. In Basque the novel is called Belarraren ahoa, the mouth of the grass, which in my mind conjures up an image of a blade of glass that’s split in the center, along its central line, with a little opening that’s like a mouth. When we were kids we used to whistle through those, or make crowns, earrings, bangles, using those “mouths” to wave the blades of grass together. I think the idea behind the title is that “the mouth” is what allows the blade of grass to become something else. Because the novel takes place in an alternate reality, a reality in which Hitler has won WWII and is set on conquering America. And that “mouth” is also the gap through which the imagination enters and re-configures the blade of grass as something else. I knew early on that I wanted the blade in the title, to maintain that idea of a cut and to keep the b from belarra, but it took me a while to come up with blade of . . . light. It came, eventually, from a scene in the book. A light that finds a way through the darkness.

In both novels, but especially in Twist, the beauty of the Basque is captivating. Harkaitz’s style has evolved and refined over the years, his Basque is so rich and polished, and the opening section of Twist, especially when the bones wake up, is so powerful and poetic, so impactful. It was imperative to me to achieve the same effect in English. I loved writing that, that was joy. Challenging joy, but joy all the same.

In both novels, but especially in Twist, the beauty of the Basque is captivating. Harkaitz’s style has evolved and refined over the years, his Basque is so rich and polished, and the opening section of Twist, especially when the bones wake up, is so powerful and poetic, so impactful. It was imperative to me to achieve the same effect in English. I loved writing that, that was joy. Challenging joy, but joy all the same.

More difficult were all the sex scenes. I think there are 6 in total. It’s very easy to write bad sex scenes and not so easy to write good ones. I thought the scenes in Basque were very good, very natural, but English doesn’t have the same register for sex . . . it’s a more prudish language. So it was a delicate balance I had to find. I hope I succeeded! It was hard but fun to translate those scenes.

The other aspect that required a lot of research was all the legalese. I’m not familiar with that language so I had to learn it. I mentioned this to Harkaitz, scolding him for giving me such a lot of work with that and he laughed, saying “I knew I would be putting my law degree to use at some point in my life—Twist was it. I had to put it somewhere. It was a relief to use that knowledge, I’d been feeling guilty for years about studying it for so long and never practicing the law. Now I can rest in peace.”

Another enjoyable aspect was all the detail about the artist Joseph Beuys. I learned a lot about him, had to consult a lot of secondary references, but it was immensely fun. I watched videos, read about his work. It was fascinating and tremendously enriching. I love that about literary translation. All the stuff you end up learning.

CWP: Are there other Basque authors you’re working on—or have samples of—that are still looking for an American publisher?

AG: Yes! I am looking for publishers for Alaine Agirre’s poetry collection Where Birds Never Visit, a brilliant, striking collection written by a new, young, neurodivergent writer at the time of her psychiatric breakdown and consequent hospitalization, and also for Katixa Agirre’s Mothers Don’t, a hybrid thriller-autofiction-essay about motherhood, female artists, and women who kill their own children that’s getting rave reviews everywhere. I would like to translate Katixa’s previous novel too, an experimental road novel, but I know Mothers Don’t is the one to do first. I’m also looking for a publisher for Juanjo Olasagarre’s Complex Bliss, a novel about gay love and Basque politics, something we haven’t seen in Basque literature. The novel takes place over the span of 20 years in the relationship of a journalist and a translator, and the characters’ sexuality is incidental to the story. Juanjo Olasagarre has said that it’s a gay novel but not a gay novel.

AG: Yes! I am looking for publishers for Alaine Agirre’s poetry collection Where Birds Never Visit, a brilliant, striking collection written by a new, young, neurodivergent writer at the time of her psychiatric breakdown and consequent hospitalization, and also for Katixa Agirre’s Mothers Don’t, a hybrid thriller-autofiction-essay about motherhood, female artists, and women who kill their own children that’s getting rave reviews everywhere. I would like to translate Katixa’s previous novel too, an experimental road novel, but I know Mothers Don’t is the one to do first. I’m also looking for a publisher for Juanjo Olasagarre’s Complex Bliss, a novel about gay love and Basque politics, something we haven’t seen in Basque literature. The novel takes place over the span of 20 years in the relationship of a journalist and a translator, and the characters’ sexuality is incidental to the story. Juanjo Olasagarre has said that it’s a gay novel but not a gay novel.

CWP: What advice do you have for someone starting out in translation?

AG: If you love it, if you really-really love it, if you love how it makes you feel and what it does to your brain and your ability to write, and the doors it opens (in life and in the mind) . . . don’t ever give up. Keep pressing the button until the dam door opens. Because it will, eventually, if you persist. Above all, meet other translators. Join a collective. Create a collective if there isn’t one where you are. Send extracts and poems and short stories to journals. Get in touch with authors. Write to publishers. It might take a few years to establish yourself, but the rewards of this profession are too many and too joyful to miss. There’s crap of course, like there’s crap in everything in life (late payments, shortsighted, intransigent editors, annoying book covers . . . ), but the pluses are great, and other translators are the best people in the world. Invariably, yes. Translators are the best of all humans. It’s a marvelous profession. We might not be rich, but we definitely have the best conversations and the most fun. Especially at ALTA conferences!

And: ALWAYS polish your drafts. Never hand in a draft that isn’t ready. Read your work out loud. Better still, read it out loud with another pair of ears in the room. You’ll hear everything that’s wrong with it then, and you’ll know what to do to fix it.

Don’t be afraid of the editing process. Be open to suggestions and criticism. When you’ve just translated a text you’re often too involved with it to see it objectively. At that point, it exists in a kind of limbo between the two languages. If you have time to put it away and look at it again in a week or two, do that. Polish it. Then show it to other translators, or to friends with literary abilities. Other eyes will see things in it you can’t see. And that’s part of the beauty of the process. But, also, think through and have a firm grasp of your own translating strategy. Be ready to back up your decisions to translate things a certain way: this is your creation after all. You are the artist here. You know what you want to do with it. There’ll be people who’ll want to push you to make everything very “proper-English” and very “but that’s how you say it,” but sometimes a translation requires daring-do and breaking rules, and that’s fine too. Just have your arguments ready.

Be inspired. Know that your translation is a unique work of art. Pour into it everything that will make it shine.

Leave a Reply