Slave Old Man [Why This Book Should Win]

Check in daily for new Why This Book Should Win posts covering all thirty-five titles longlisted for the 2019 Best Translated Book Awards.

Sofia Samatar is the author of the novels A Stranger in Olondria and The Winged Histories, the short story collection, Tender, and Monster Portraits, a collaboration with her brother, the artist Del Samatar. Her work has received several awards, including the World Fantasy Award. She teaches African literature, Arabic literature, and speculative fiction at James Madison University.

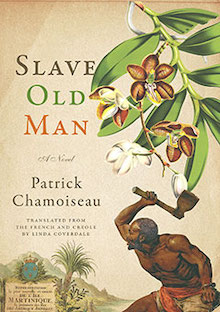

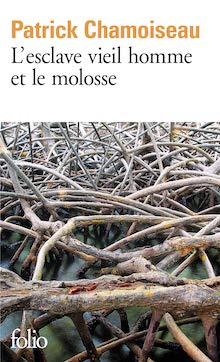

Slave Old Man by Patrick Chamoiseau, translated from the French and Creole by Linda Coverdale (Martinique, New Press)

Twenty years.

It was 1996 when Patrick Chamoiseau finished writing L’Esclave vieil homme et le molosse, 1997 when the novel was published, and 2018 when Linda Coverdale’s translation, Slave Old Man, appeared in English.

Those two decades, during which Slave Old Man was not yet here, seem to me like a mysterious abyss. They seem like the forest spring at the heart of the novel, where the old man, enslaved for as long as he can remember, tumbles in his flight from the master’s vicious mastiff (the molosse of the French title). The spring is a place of death and rebirth. It’s a well of utter passivity, where time stops, where the exhausted flesh gives up hope. It is also a place of vision. Language erupts here, and red crabs swarm. It’s not how long the old man is held in the water that matters, but what he will become.

This is a radiant novel of fugitive life—of those who remain, in the face of terror, “catastrophically alive.” Coverdale renders Chamoiseau’s complex language beautifully into English, developing her own surprising strategy for Creole words, both translating them and leaving them in place. So the word molocoye, “tortoise,” becomes “molocoye-tortoise.” The old man is “djok-strong”; the memories of enslaved Africans form a stew, a murky “calalou-gumbo.” The method delivers clarity without sacrificing the richness of Chamoiseau’s two languages, and by creating new constructions, Coverdale gives standard English a lively, improvisational, oral feeling. It’s an approach that suits this experimental novel, which is both fable and philosophy, deeply engaged with the work of Chamoiseau’s fellow Martinican, Édouard Glissant, whose writings are quoted at the head of each chapter. The chapter titles lay out the novel’s themes, like a path into the forest. Matter. Alive. Waters. Lunar. Solar. The Stone. The Bones.

This is a radiant novel of fugitive life—of those who remain, in the face of terror, “catastrophically alive.” Coverdale renders Chamoiseau’s complex language beautifully into English, developing her own surprising strategy for Creole words, both translating them and leaving them in place. So the word molocoye, “tortoise,” becomes “molocoye-tortoise.” The old man is “djok-strong”; the memories of enslaved Africans form a stew, a murky “calalou-gumbo.” The method delivers clarity without sacrificing the richness of Chamoiseau’s two languages, and by creating new constructions, Coverdale gives standard English a lively, improvisational, oral feeling. It’s an approach that suits this experimental novel, which is both fable and philosophy, deeply engaged with the work of Chamoiseau’s fellow Martinican, Édouard Glissant, whose writings are quoted at the head of each chapter. The chapter titles lay out the novel’s themes, like a path into the forest. Matter. Alive. Waters. Lunar. Solar. The Stone. The Bones.

How current it seems—prescient, even—this novel written more than twenty years ago! It’s a book that seems to have emerged from its own afterlife. It doesn’t feel timeless, but futuristic—like a ray cast backward into 1996 from what Black Studies would become twenty years later. So Slave Old Man gives me a buzzing, disoriented feeling, because the old man’s broken, persisting flesh is the living-dead matter of Alexander Weheliye’s Habeas Viscus (2016), because his watery memories of the hold, echoed by his rebirth in the spring, seem written in the wake of Christina Sharpe’s In the Wake (2016), because his exuberant voice, issuing out of a body marked for disposal, echoes the transformative trash-heap poetics of Fred Moten’s Black and Blur (2017), and because the bloodthirsty mastiff, carried to the Caribbean on a slave ship, might have been drawn from the pages of Bénédicte Boisseron’s Afro-Dog (2018).

What is going on here? Did everybody read L’Esclave vieil homme et le molosse in French twenty years ago and I was the only one who missed it? Or is it that I’m looking at an Édouard Glissant constellation (thinking especially of Moten’s kinship with Glissant)? Or—to quote the epigraph to Slave Old Man—“DOES THE WORLD HAVE AN INTENTION?”

Whatever the reason, Slave Old Man deserves to win the Best Translated Book Award, both for Linda Coverdale’s brilliant inventiveness as a translator, and for Patrick Chamoiseau’s achievement in writing, back in 1996, a novel so uncannily ahead of its time that it appears to have arrived in English not late, but early.

Leave a Reply