Comemadre [Why This Book Should Win]

Check in daily for new Why This Book Should Win posts covering all thirty-five titles longlisted for the 2019 Best Translated Book Awards.

Aaron Bell is a wage laborer and Doctor of Philosophy.

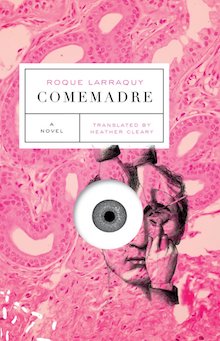

Comemadre by Roque Larraquy, translated from the Spanish by Heather Cleary (Argentina, Coffee House Press)

Comemadre is a series of nightmares relentlessly pursued to their logical conclusions. Initial premises, once established, are developed without remorse. Each idea in the novel is embryonic, slowly developing and taking deformed shape. Each sentence proceeds from the last with near-logical necessity, but somehow still manages to continually shock and disturb. Given this central element of shock, I’m going to avoid as many plot details as I possibly can.

Formally, the novel is composed of two stories that initially appear to have little in common: the first takes place in a sanatorium in 1907 and the second profiles the life of a notorious performance and installation artist in 2009. As Larraquay himself puts it, the novel is an experiment in “sew[ing] together two different narrative materials and forc[ing] them [to] live together in a reciprocally parasitic way, to unite them gradually in one multiple and continuous body, an unexpected flowering.”[1] The parasitic interweaving of the stories begins slowly, first through the blooming of complimentary themes, then through the actual interpenetration of shared characters and narrative details. What emerges from this synthesis is a world where the will to power and the will to know are indistinguishable, and the desire to create and dominate are practically identical. Reason and creativity, bereft of care and concern for others, are aimless accomplices to caprice, cowardice, murder, and the lust for power.

The protagonists of each story are united by a phrase, first uttered in part one and then quoted directly in part two: “That’s what we’ll do, because we have the means, and because we were first to think of it.” (25, 124) This phrase distills the careerism and aimless nihilism that animate the characters. They both pursue their projects without truly believing in them, cynically relying on the ignorance or poor judgment of those around them. The doctor of part one of the story believes as little in medicine as the artist of part two believes in the art world. The practice of medicine and art are simply means to elevate oneself and wield power against others.

The history of political violence in Argentina is alluded to throughout the novel, but Larraquay’s main focus is biopolitical violence. The sanatorium is the site of atrocity, not the prison or camp or rural village. Doctors, not right-wing militias or soldiers, prey upon the poor and ignorant through false diagnosis, coercion, and manipulative experimentation. No political ideology pervades other than the belief that all bodies are interchangeable material to be used, and only those who hold power are exempt from this leveling.

Larraquay masterfully transports these themes, so often explored in Holocaust literature, into the unexpected settings of a nineteenth-century provincial sanatorium and the modern art world. Departing from the familiar setting of the concentration camp allows Larraquay’s world to constantly surprise and disgust with his alternating currents of black humor and horror. His novel dramatization of the themes of bureaucratic murder, reason without an end, the banal evil of bureaucracy, etc., reinvigorates them in a way that feels wholly his own, unlike anything I’ve ever read.

Larraquay masterfully transports these themes, so often explored in Holocaust literature, into the unexpected settings of a nineteenth-century provincial sanatorium and the modern art world. Departing from the familiar setting of the concentration camp allows Larraquay’s world to constantly surprise and disgust with his alternating currents of black humor and horror. His novel dramatization of the themes of bureaucratic murder, reason without an end, the banal evil of bureaucracy, etc., reinvigorates them in a way that feels wholly his own, unlike anything I’ve ever read.

Despite Comemadre taking place in a slightly more excessive version of our world, its themes are as applicable to our lives as ever. While the world of the turn of the century sanatorium is shaped by pseudo-scientific nonsense (phrenology, debunked psychological theories and cures, etc.), its worst tendencies are alive and well today. Comemadre is a powerful critique of our administered, bureaucratic world, full of petty men wielding power with impunity. Mass incarceration, the farce of our private healthcare system, our continual exploitation at work, all express the same kind of relentless and unfeeling logic that Larraquay dissects and parodies. The release of Heather Cleary’s translation, while delayed ten years from La Comemadre’s initial publication, is timely. Unfortunately, it’s hard to imagine a past or present moment in the last century that this book would not feel timely.

Leave a Reply