Interview with Janet Hong [Graphic Novels in Translation]

Off to a bit of a slow start here, but this month’s focus on Three Percent is going to be graphic novels in translation. I’ll have a post up on Monday about some Drawn & Quarterly titles I’ve been reading, then one on NYRB Comics later in the month. Also hoping to have another interview or two, but I’ll keep those to myself until they’re confirmed.

But up first is the following conversation with Janet Hong, winner of the TA First Translation Prize, translator of Ha Seong-nan’s Flowers of Mold (which is selling really well for us!), and of Bad Friends by Ancco, about which I’ll have more to say on Monday.

Even if you haven’t read Bad Friends, or know just a little about it, I think you’ll find this interview really interesting. And I want to publicly thank Janet for taking time out between her vacations to answer all these questions so thoroughly.

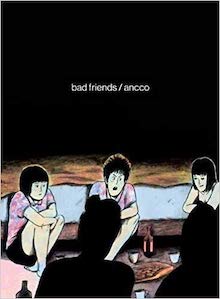

Bad Friends by Ancco, translated from the Korean by Janet Hong (Drawn & Quarterly)

Chad W. Post: Before we get into talking about Ancco’s Bad Friends, I wanted to ask you about your career in translation in general. Recently on Twitter you mentioned that Flowers of Mold by Ha Seong-nan (which we just published at Open Letter) was the first book you translated—18 years before it was published in English! Yet, within the last couple years, you’ve had Impossible Fairy Tale by Han Yujoo come out—which earned you the TA First Translation Prize—and now Bad Friends. What has this journey as a translator been like for you? Has anything changed—culturally, or with publishing—that led to getting so many books picked up in such a short period of time?

Janet Hong: You said it—it’s been a journey in every sense of the word. As I mentioned before, a story from Flowers of Mold—“The Woman Next Door”—is the first translation I’d ever attempted, as an end-of-term project for a Korean language course in my undergrad. My professor urged me to submit it to the 2001 Korea Times translation contest, and I ended up receiving the grand prize, and then a grant soon after to translate the rest of the collection. In my ignorance, I assumed everything would happen fairly easily and quickly, so I’ve wondered many times myself why it’s taken ridiculously long to have a book-length translation come out, and then have several follow right on the heels of one another. Maybe I’d needed to begin on a high note to sustain me for the long road ahead?

Just to clarify, Korea has always enjoyed a strong literary tradition, with authors producing intellectually and aesthetically diverse work that is constantly evolving, so it isn’t that Korean literature went through a major change. However, it is true that there was very little interest in translated Korean literature when I was starting out, so timing played a huge role in Korean literature gaining a global appeal. Even ten years ago, Korea—despite its long, rich literary history—remained a largely untapped literary mine, yet there were several crucial elements already in place: the Korean Wave, or the mass popularity of South Korean culture, which had been building since the nineties; the success of Kyung-sook Shin’s Please Look After Mom, which was published in the U.S. in 2011; and Korea being the Market Focus of the 2014 London Book Fair. The publication of Han Kang’s The Vegetarian and its 2016 Booker win were like putting a lit match to dry tinder.

Just to clarify, Korea has always enjoyed a strong literary tradition, with authors producing intellectually and aesthetically diverse work that is constantly evolving, so it isn’t that Korean literature went through a major change. However, it is true that there was very little interest in translated Korean literature when I was starting out, so timing played a huge role in Korean literature gaining a global appeal. Even ten years ago, Korea—despite its long, rich literary history—remained a largely untapped literary mine, yet there were several crucial elements already in place: the Korean Wave, or the mass popularity of South Korean culture, which had been building since the nineties; the success of Kyung-sook Shin’s Please Look After Mom, which was published in the U.S. in 2011; and Korea being the Market Focus of the 2014 London Book Fair. The publication of Han Kang’s The Vegetarian and its 2016 Booker win were like putting a lit match to dry tinder.

I think my own approach as a translator has also changed quite a bit from when I first started. I find most literary translators focus their energies on translating novels, rather than short story collections, because it’s already notoriously difficult getting publishers to take on translations, but it’s even more difficult to get them to take on short stories in translation. Translators will sometimes work on a few short stories by their authors and place them strategically in journals to whet readers’ appetites, but the novels are always the main course. Still, that never stopped me from going after short stories, because I personally love them and my favorite authors to this day are masters of the form, like Alice Munro. Maybe if I’d pursued more novels earlier on, I wouldn’t have had such a long wait?

Besides translating mostly short stories, I also wasn’t very picky in the beginning and said yes to every translation job that came my way—movie subtitles, picture books, plays, book blurbs and proposals, samples of fiction/self-help/biographies/memoir/children’s, I did it all. Sure, I was getting lots of practice, but I could have been wiser with my time, focusing on projects I was truly passionate about, instead of trying simply to make money.

When my first full-length translation—Han Yujoo’s novel The Impossible Fairy Tale—was published in 2017, it was sort of a wake-up call for me. At that point I’d been working as a literary translator for nearly 16 years, but I felt I had hardly anything to show for it. I realized I had at least two collections by Ha Seong-nan that I’d already translated sitting in my computer—that’s when I queried you about Flowers of Mold.

Which leads to a realization I had: As a literary translator in today’s world, it’s not enough to just translate. Unless the authors you translate have literary agents (and even when they do!), you have to take on a more proactive role, actively connecting with agents/editors/publishers to hustle the work yourself. So these days, especially for my authors who don’t have agents, I’m the one pitching to editors and publishers. I also try to connect my authors with agents. And I don’t make any commission. It’s because I believe the work I have the privilege of translating is so good it needs to be shared and read.

CWP: It’s interesting to me that the three tiles mentioned above cover three different forms: a novel, short stories, a graphic novel. Do you feel more comfortable translating one type of writing versus the others? Which—if any—poses the most challenges to you as a translator? I can imagine a novel being tricky because of all the interlocking aspects, or resonances that connect across dozens of pages; short stories being hard because of their brevity and concise prose; and graphic novels because of the space restrictions . . .

JH: Since I’ve worked on many short stories, I’m probably most comfortable with this form, but I find translating novels isn’t all that much different. What poses the most challenges to me, honestly, is Han Yujoo’s writing. Ha ha. Her work relies heavily on wordplay to build suspense, as well as to move the narrative forward. In fact, she’s all about dismantling the traditional narrative to demonstrate that fiction isn’t just a story—that it doesn’t have to be—and she does this by playing on the Korean language. As the translator attempting to replicate this in another language, I sometimes wonder if I’m fighting a losing battle, but when I manage to find a solution of some sort, I feel an immense satisfaction that’s hard to describe.

I also find translating sound effects in graphic novels to be extremely difficult. Because so many Korean words are based on onomatopoeia, I spend way too much time trying to find the perfect word that describes, say, the sound of metal hooks sliding along a curtain track. Maybe I’d have an easier time if I’d been immersed in the comic universe, but I guess it’s getting a little easier!

CWP: How did you come to work on Bad Friends? Were you part of the process in bringing this to Drawn & Quarterly’s attention?

JH: No, not at all. Except for a few like Art Spiegelman’s landmark Maus, Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis, and Guy Delisle’s books about his travels, I hardly read graphic novels before, let alone Korean graphic novels.

It was D&Q who got in touch with me—they’d gotten my contact from a representative at LTI Korea. They were looking for a translator to work on several Korean graphic novels they were planning to bring out, which they’d only read in French translations. They asked if I could provide a few translation samples, including one of Bad Friends—in other words, I had to audition for the job. I wasn’t entirely sure if I wanted to get into translating graphic novels, since the work seemed quite painstaking and I was pretty certain it wouldn’t be financially lucrative (not that translating fiction means the big bucks!), but as soon as I read Bad Friends, I became practically possessed. I knew I had to translate it.

It was D&Q who got in touch with me—they’d gotten my contact from a representative at LTI Korea. They were looking for a translator to work on several Korean graphic novels they were planning to bring out, which they’d only read in French translations. They asked if I could provide a few translation samples, including one of Bad Friends—in other words, I had to audition for the job. I wasn’t entirely sure if I wanted to get into translating graphic novels, since the work seemed quite painstaking and I was pretty certain it wouldn’t be financially lucrative (not that translating fiction means the big bucks!), but as soon as I read Bad Friends, I became practically possessed. I knew I had to translate it.

Since it was my first graphic novel and I wanted to do it justice, I spent a ludicrous amount of time on the translation and revision. Though they were gracious beyond belief, I probably drove the editors crazy with my incessant tweaking. It got to the point where my husband would joke I was losing money each time I opened the Bad Friends file on my computer to fuss some more. That’s how much I love that book. I would have translated it for free.

CWP: I don’t know much . . . well, anything . . . about the South Korean comic book/graphic novel scene, so these questions might be really naive or silly, but here goes: Was this originally published as a graphic novel, or was is serialized in some way (either in shorter volumes or online)? Is Ancco’s work representative of the Korean scene? If so, are the books always this dark and violent? (There are so many bleak parts of this book!)

JH: Bad Friends was never serialized; it was originally published as a graphic novel. It won the Korean Comic Today prize in 2012, and the French translation was the first Korean graphic novel to win the prestigious Prix Révélation at Angoulême in 2016, making Ancco the second Asia-born cartoonist to be awarded the honor. Until Bad Friends, I knew nothing about the South Korean comic/graphic novel scene, but I’m seeing in the few Korean comics I’ve read or translated recently an extremely wide range in style, subject, tone, and treatment. For example, the incredibly evocative, tender, and heart-wrenching comic I worked on recently—Umma’s Table by Yeon-sik Hong—left me in tears, just as Bad Friends had, but I’d say the two books sit on opposite poles of the Korean comic world.

CWP: As someone more familiar with structures and literary techniques in traditional prose narrative, I’m struggling trying to figure out how best to describe the ways in which this narrative come together—the uniqueness of how it’s told. Do you have a good way of explaining this book? And/or do you have any suggestions for readers new to graphic novels about how best to approach and read them?

JH: You know, I hardly even noticed the structure at first. I think the brutal aspects shocked me into just going with the story; I couldn’t tear myself away. R.O. Kwon, who wrote a blurb for the book, said a similar thing, about how she’d meant to read just a few pages before getting up for a glass of water, but ended up reading the whole thing glued to her chair, while completely parched.

In short, I think the flashbacks and sections broken up into different periods of Pearl’s life suit the narrative extremely well. One reviewer said the approach is reassuring, because it tells the reader that Pearl survived the extreme violence of her past. The sections in the present also offer the reader some much-needed relief from the bleak chaos of the earlier years.

In short, I think the flashbacks and sections broken up into different periods of Pearl’s life suit the narrative extremely well. One reviewer said the approach is reassuring, because it tells the reader that Pearl survived the extreme violence of her past. The sections in the present also offer the reader some much-needed relief from the bleak chaos of the earlier years.

For me, the back-and-forth between past and present almost mirrors the way we process trauma and memories. Sometimes you can only look back at grief or nightmarish events in bits and pieces from a distance, either after much time has passed or if you’ve ended up in a completely different (better) place.

The book begins with Pearl, a kind of stand-in for Ancco, who is now a well-adjusted, mostly happy cartoonist, working into the late hours of the night, as many artists do, when a certain smell brings back her turbulent youth. (By the way, Ancco has said that smells are everything to her work. She doesn’t mean the actual smell of something, but a smell that conjures a certain time or feeling. I also want to interject here that Bad Friends is a work of fiction, though many elements are based on Ancco’s life.) As Pearl reflects on her adolescence, she feels a mixture of emotions: grief over the loss of a pivotal friendship with her old friend Jeong-ae, who has a more troubled domestic life than Pearl; relief that she has managed to escape the physical abuse and sexual harassment of her past; and guilt over the fact that Jeong-ae hasn’t been so lucky. These emotions are obviously difficult to articulate and even seem to be at odds with one another, so I think the structure serves the narrative well, as Pearl tries to make sense of a time in her life that was intense, hellish, yet electrifying, and wrestles with what it means to be a good friend, or in this case, a bad friend.

CWP: Are there other Ancco books in the works? Or any other projects that you’re working on that you’d like to pitch?

Yes, there is! I’m scheduled to translate Ancco’s Nineteen, an earlier short story collection that Drawn & Quarterly will be bringing out in 2020, which was published in French as Aujourd’hui n’existe pas. It’s different from Bad Friends—not as violent, but just as bleak and powerful. In one story, you can see the beginnings of what eventually became Bad Friends.

At the moment, I’m working on some really dark, transgressive stories by Kim Yi-seol, as well as the work of extraordinary feminist author Kang Young-sook, whom I met on my most recent trip to Korea through none other than Ha Seong-nan. Kang writes about the female grotesque, delving into varying genres as urban noir, fantasy, and climate fiction, and she also happens to be one of Ha’s closest friends. I’m beyond excited to share Kang’s award-winning story, which will be published in the next issue of The White Review.

Leave a Reply