“Tentacle” by Rita Indiana [Why This Book Should Win]

Check in daily for new Why This Book Should Win posts covering all thirty-five titles longlisted for the 2020 Best Translated Book Awards.

Tobias Carroll is the author of the books Reel, Transitory, and the forthcoming Political Sign.

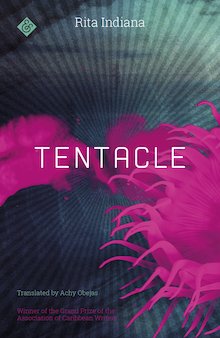

Tentacle by Rita Indiana, translated from the Spanish by Achy Obejas (And Other Stories)

Rita Indiana’s Tentacle is a novel I’ve written about multiple times, which might give you a sense of how I feel about it. Some short novels use their size to deliver a hyper-focused dose of plot and setting to the reader—immersing them in a character’s psyche or exploring the ramifications of a particular action. Tentacle goes in the opposite direction: part of the novel’s charm is in checking off all of the things that Indiana includes in the narrative. A partial list would include environmental catastrophes, time travel, gender and society, and the Caribbean’s relationship to the rest of the Americas.

As translated by Achy Obejas, Tentacle is a compelling combination of seemingly disparate elements. Its protagonist, Acilde, leaves a dystopian future for a voyage back in time, to avert the catastrophic circumstances that led the world down such a bleak path—but it’s also a journey that effectively bifurcates Acilde’s consciousness. Acilde finds a fulfilling life once he arrives in the past, and there’s an ecstatic element to some of these passages—the allure of an idyllic life in a scenic location while great music can be found. (If you’re a fan of Giorgio Moroder’s work, you’ll find plenty to enjoy here.)

Indiana deftly illustrates Acilde’s existence in simultaneous times, sometimes in the same paragraph:

He thought the late twentieth-century life in Sosúa playing out in his head might be a side effect of the Rainbow Brite. Back in Sosúa, in the little house where the natives revered him, in front of the mirror that hung from a nail over the faucet in the yard, he assured himself, like a midwife with a newborn, that this new body didn’t need anything else.

Acilde’s adventures in time are juxtaposed with a more overtly satirical plotline set in the past timeline about a misanthropic, frustrated artist named Argenis. The way the novel’s two plotlines eventually converge isn’t initially apparent; instead, Indiana plants clues to the novel’s resolution throughout the narrative, and does little hand-holding of the reader as Tentacle reaches its conclusion.

In other words, there isn’t just a contrast between Tentacle’s blissed-out segments and its dystopian elements. There’s also a greater one between its familiar segments and the subtler plotting that Indiana does throughout the novel. This is a book which rewards multiple readings, in a way that’s oddly reminiscent of the works of Gene Wolfe. (Despite the fact that this is, otherwise, very far removed from the fictional territory that Wolfe covered.) Did I mention there were pirates? There are pirates, too.

Writing about Tentacle in The Guardian last year, Suzi Feay observed that “Tentacle reads like Kathy Acker with a tighter narrative grip.” Indiana’s novel has plenty in common with the work of Acker or Iain Sinclair, including an unruly and politically charged blend of realism, satire, and the uncanny. And if you think that comparing Indiana’s work to two other writers whose work is famously difficult to pin down is a bit of a paradox: exactly. This is an author whose fiction carves out its own distinctive space, both familiar and fresh.

Leave a Reply