Baudrillard in the Time of COVID / Baseball Is Back!

There are two types of people who read these posts: people into international literature who like baseball, and those who don’t.

What follows is an experiment—one that might not work at all.

Before you get started, you have a choice: 1) if you hate genuine writing about baseball, then click here, where I’ve edited out all extraneous references to baseball; 2) if you’re only here for the random baseball musings about stats, fun players, small sample sizes, and Sam Miller, then click here, and binge on that; and 3) if you want the best of both worlds, read what’s below, although be warned that there are passages in each of the other two posts that don’t exist below. (And those bits are pretty funny, digressive, and, well, maybe the core of the argument. Who knows! It’s an experiment.)

*

There’s never been a better time to read Baudrillard. There’s also never been a worse.

Thanks to quarantine, the unprecedented nature of this situation, Trump, government response to the protests—everything feels like an illusion. Not an illusion in the sense that “nothing is physically realm,” although one could argue that scientists have yet to prove the immutable, primary substance giving rise to reality, and cosmologists never get to the end of the universe—two scientific situations that can really call into question the concept of “reality.” But no, I don’t want to argue that we’re all living in some wild constructed world, or, better yet, a Westworld-style simulation of Jean Baudrillard’s final acid trip.

[Disclaimer: I have no idea if Baudrillard dropped acid.]

Instead, I want to talk about how 2020 is the Year of Illusions—both in physical and ideological domains—and that the acknowledgement of how these illusions have propped up various power structures could, theoretically, usher in a time of radical change.

*

COVID-19 is the most Baudrillard of all catastrophes I’ve lived through. The 9/11 attacks were the previous high-water mark, given the significance and emotional impact the destruction of the Twin Towers had on people who only saw it on TV—people who maybe have never been to NYC, even now, twenty years later—or heard about it on NPR; experiences that are mediated in one way or another.

On the way to work that particular morning, I didn’t have NPR on at all. Instead I was listening to Crooked Rain, Crooked Rain (not joking), while driving a new employee to the Dalkey Archive offices out in Funks Grove, an extremely remote wooded area surrounded by the largest fields you’ll ever see; a setting that made the approach to John O’Brien’s house—planted at the border of the woods and fields, right where the road curves 90 degrees to the right—feel like you were about to drive off the edge of the world.

It wasn’t until we were out of the car, walking toward the office door that Angela (another employee and John’s wife) yelled to us that the Twin Towers had been attacked.

I can’t remember if we saw the second tower fall “live” on TV, or if we only saw the replays. All the replays. The scroll. That will never, ever go away. The moment that we—the U.S., the Western world, everyone—entered into our current moment of hyper-anxiety, an new sense of dread coupled with an inherent understanding that not matter when, or where, a catastrophe takes place, in a short order of time, we’ll be able to see footage of it online. All catastrophes are now viewable, almost immediately. It was ’63, but with the Internet.

The fact that this was such a video-centric occurrence—both at the Twin Towers and the Pentagon—witnessed in real-life by a tragic number of people, but internalized by so many millions of others who chose to create their own narratives about the how and why of it all only enabled the spread of the suspect conspiracy theories, the over-analysis/doctoring of images, the mobilized hatred against a specific group of people.

And for many, these illusionary beliefs have become real. Have lead them down an increasingly questionable and walled off set of opinions (or straight out falsehoods) masquerading as “fact,” and existing in a miasmic digital world in which “reality” is based on which illusion you prefer.

*

The other day, the Major League Baseball season—or, rather, “season,” given that it’s 60 games; given that instead of ten teams making the playoffs, sixteen will, which is more than half the league; that every extra inning starts with a runner on 2nd base, which is very weird; and, obviously, COVID protocols and a 60-man taxi squad for dudes who test positive—kicked off. The first game was rained out. Because of course. 2020!

But the first weekend was almost a success! Baseball was played, playoff odds shifted, Flaherty flourished, the Cards won two and then lost, and Ohtani got ROCKED. Which broke my heart. Watching Shohei Otahni and Mike Trout at the top of their games is a gift to baseball fans everywhere.

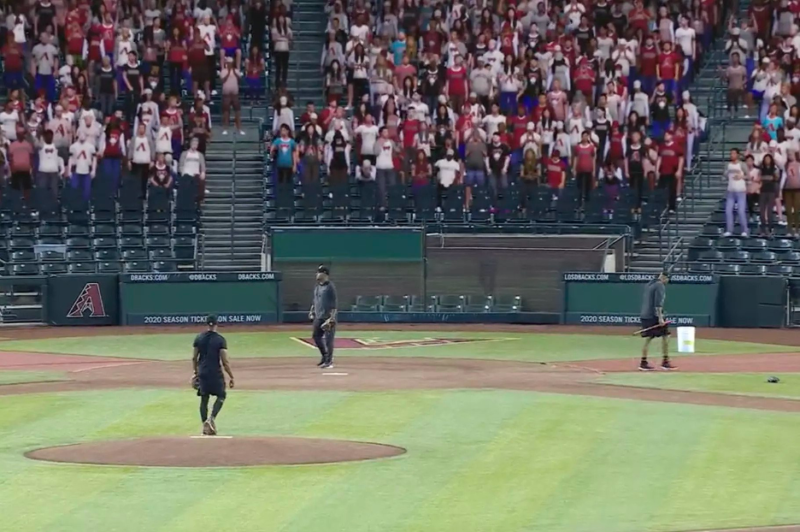

Given how awful this summer is (I just remembered this song earlier today and am now playing it to death), baseball, this never-ending, not very popular game that’s being played with no fans—well, there are plastic/cardboard(?) cut-out fans in some stadiums, totally mis-sized, the things of nightmare, and, unfortunately, sturdy, depriving all of us of the joy of seeing Joey Gallo decapitate some dude’s dog—could be my only real joy until . . . God only knows. But as much as I’m willing to overlook in order to at least have baseball, there is some weird shit that deserves attention.

*

The invisibility of COVID—not only the fact that the virus passes among us, unseen, but that you can have it for days and not even know, and that we’re witnessing the deaths it causes via Zoom, saying goodbye to loved ones over an iPad—is extremely dangerous when it comes to public health.

This is where the “illusionary” nature of COVID, emphasized by the fact that we discuss it in terms of numbers (of cases, of death rates, of positive test percentages) separates the true horror of the virus’s impact from the common discourse. It allows Trump to blatantly lie, because a vast majority of his base hasn’t seen anyone die from COVID in person.

Questioning the existence of COVID—and how contagious it is and how it can be contracted—because you can find videos or blog posts “exposing” it as “fake news” is a significant reason in why America destroyed the summer of 2020. And probably the rest of the year as well.

Despite the omnipresence of illusionary beliefs in our lives, a lot of people are really bad at identifying the illusionary component and understanding how the structures-that-be use your belief in one small thing in order to push a larger agenda. There’s a straight line from anti-vaxxers to protestors trying to reopen the economy. Create one false belief—such as Trump saying the virus will just go away—and you can get a massive group of Americans to believe that there’s no reason to keep bars and beaches closed.

The thing about baseball, the number one reason I like it, is because every single aspect of the game is difficult. Throwing a baseball so incredibly fast, or with such movement, that a grown man with a bat—who has hit tens of thousands of baseballs in his life—will miss it enough times that he strikes out seems impossible. (The season with the most strike outs ever was last year, 2019, with 42,823.)

The idea of hitting a ball—be it a 95 mph fastball, letters high, or a slider gliding across the plate at 82—seems equally impossible. Even in the “good old days,” hitting .350 was an incredible feat—meaning you still failed almost two-thirds of the time. (The most homeruns in a season was last year, with 6,776, a whopping 671 more than the previous record. That’s approximate a 10% increase in the record.)

Fielding isn’t very fun either. Not that players don’t mostly succeed at this—there are players who have a lifetime fielding percentage above 99%, the league as a whole was at .985 in 2013, and that’s normal—but every time a player doesn’t make a play, the crowd reacts as if they aren’t doing a nearly impossible task every other time a ball comes their way. Watch a MLB player dive for a ball at third, get up, and throw out a world-class athlete sprinting down the line and then imagine yourself in that situation. Imagine tracking a ball that goes a couple hundred feet in the air and covers 350 feet on the ground. It’s easier than anything else I’ve mentioned, but definitely not easy. Nor is stealing bases! It’s all hard!

Which creates such a beautiful equilibrium. Everything that happens in a game feels equally unlikely.

*

One of the most interesting perspectives that’s been floating around recently is the idea that streaming platforms will “run out of content” at some point because filming was shut down. This statement belies our addition to the new. None of these platforms will ever be devoid of content, and in no possible future will every subscriber have watched every minute of programming they currently offer.

If Netflix started targeting specific users with information about more obscure properties that that user hadn’t previously watched, it would take, most likely, a banner ad and an appearance on the Netflix home screen to convince the viewer that this was a new program.

There is simply too much content. A counterintuitive result of the hyper creation of content—to the point where it seems like there are infinite viewing options—is the way in which this instills a desire within viewers to consume as much of it as possible. Guided by whomever your social-cultural guides are. Friends. Celebrities. Algorithms. Websites. Twitter personas. A still.

Now that the fragmentation of culture is total and complete, and we live inside a million different possible influencing attributes, allowing us to see everything, and have no idea why one cultural product becomes the strange attractor for seemingly everyone and another doesn’t. At best, it can be traced back to a few other things that seemed to happen, usually simultaneously—a celebrity endorsement, a Netflix deal, a particular review, buzz about the author—but all of these explanations tend to ring hollow. The illusion is created that the publisher/producer/record company knew what was going to happen, given all these little seedlings of interest, and by believing in that, we feel like the rise of a particular book or movie was inevitable. Planned. That the producer of the cultural item is cognizant of what they’re doing—and definitely worthy of being trusted in the future.

The randomness of crowds has been replaced by the illusion of mass persuasion, aided by the fragmentation of information and narrative.

*

Sure, the 60-game 2020 season is a “sprint,” and I kind of totally love it, since the stakes seem so much higher for each individual game, but it’s not nearly the same as being incredibly invested in the final 40 games after a 122 game grind. By this point, statistics have stabilized; everyone on the field has a plan on how to approach each other. Winning in September is winning when teams have the most knowledge about how to defeat individual tendencies. It’s not a fully mental game, baseball, but it’s a game in which, since its inception, people have been trying to drill down to figure out the essential question: “In this game of mostly failure, why did this work?”

You can start by looking at how often a player misses a 2-seamer in a particular part of the plate. How often he swings at them. What trajectory those pitches tended to have when he missed vs. when he made contact. What the likelihood is that this particular pitch will help our team win the game? And how can we leverage all of this information to win 56% of the time. (Slightly higher than a Vegas casino, but really, winning 56% of the time feels almost abusive in its inconstancy.)

*

MLB is one of the more frivolous examples of how COVID-19 has generated a ton of weird illusion-centric statements. The “crowd” noise present at every game is Peak 2020 Illusion.

For the uninitiated, although basebasll is being played, no fans are allowed in the stadiums for the foreseeable future. The visiting broadcasters call the games from their own home studios, watching the game on camera—same as the fans at home. Only a few employees—and the team mascots—are in the stadiums, which, for a professional athlete, must seem hauntingly silent.

To create the illusion that this is a “normal” season—and to allow for players to exchange information and signs—MLB is using 2020 technology to reproduce an imaginary crowd. It’s not at all difficult to blast crowd noise via the PA systems in all 30 parks, but where does one obtain said crowd noise?

This is more problematic than it might seem. Crowd noise is not uniform across stadia—compare crowd attendance at Marlins Park (10,000 a game) to Dodger Stadium (almost 50,000)—nor across game situation. Looking at the second half of that statement: Even if a team happens to have a recording of their fans cheering, and it’s high enough quality to play over a PA system with enough volume to be captured by the broadcast mics, it’s still highly unlikely that the particular volume and breadth of that specific cheer would be a perfect reaction to whatever just occurred in the live game. In this example, the “real” noise has been separated from the event that spawned it, and is an illusion on two fronts: that the crowd actually exists, and that this is what they would be doing in reaction to the play they just witnessed.

Given the near impossibility of finding enough actual clips to make this system work effectively, a video game created by San Diego Studios is piping in the simulated crowd noises into the stadiums so that “stadium sound engineers will have access to around 75 different effects and reactions captured from MLB The Show.” Presumably, these reactions are site specific—decibel- and enthusiasm-wise—to the stadium where they were originally “captured.” (That word is doing a lot of work in this press release.)

A smart sound engineer might take this a step farther. They might be wary of choosing how much to amplify a crowd’s excitement in relation to a given play. They’ve likely been around baseball for a while and gathered some sort of generalized, difficult to quantify, knowledge about crowds, but when the opposing team hits a single, do you leave the “general crowd murmur” setting at 15 out of 100, or drop it to 5? How will that impact the players on the team that employs you? What if you don’t cheer your team’s own batting accomplishments with proper volume and enthusiasm? Having to generate this illusion—that a crowd is present—is really anxiety making. Let’s use an algorithm.

*

San Diego Studios already built a simulation of what the crowd noise could/should be in every situation, at every ballpark. Theoretically, given the nature of game and world-building, the algorithm driving the sounds inside the video game could take into consideration all of the following attributes: how large the crowd is given the team’s recent success (or failure); how enthusiastic the crowd is based on what part of the season the game is taking place, and the opponent, and the perceived importance based on who is pitching, a win-loss streak, or some other aspect of the matchup that can be articulated by pundits, fans, and broadcasters. There’s no reason, as a stadium sound engineer, you shouldn’t use this algorithm. They built it off of the sounds of your fanbase (or, at least, an abstracted “MLB Fanbase” of which your stadium’s fans are represented as a deviation from the norm), and created feedback loops far more robust than yours as a single individual—imagine being the sound operator who pushes “volume” and “excitement” and “joy” all to 100% for a hit that looks like it will be out of the park, one that is easily caught by a defensive player, and then forgets to turn it down for a full ten seconds after the out is made, a situation ripe for social media—one that creates at least a “believable illusion” of how the crowd would be reacting.

Keep in mind that these sounds—artificial, determined by an algorithm that’s getting cues from a system designed to track and record every pitch—are heard both by the players on the field and the fans at home. Fans are hearing, through their TV, artificial sounds from a baseball video game, that are piped into the stadium’s PA, with their texture determined by the same video game’s algorithm, mediated by the broadcast speakers in the stadium designed to pick up the “crowd” noise, in order to relay it back into your home. If you could watch the exact same sequence of pitches and plays on MLB The Show, you would hear the exact same crowd. An illusionary crowd.

COVID-19 can disrupt almost every aspect of our lives, except for marketing, in part because marketing is the process by which companies get users to buy into illusions in order to transmute the belief that product X contains qualities sufficient enough for you to want to spend your money to obtain them. This is one of the roots of capitalism: the pathway from image to ownership.

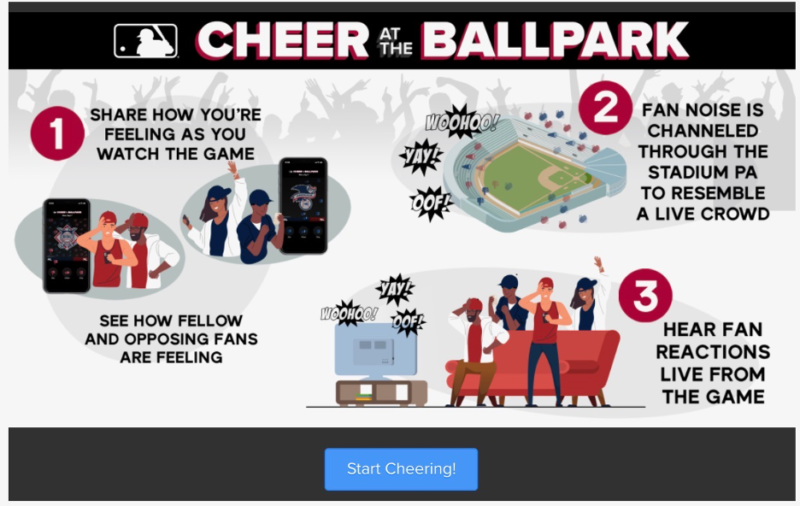

Without the ability to sell tickets, MLB introduced a different way to market their product to their fan base:

And now we’ve added another level of mediation to the crowd noise algorithm running the PA system at the park that we’re watching on our TV, with our own personal speaker system. We are somehow, in some small way, influencing what the computer knows about human reaction. How many times to cheer, at what rate, for what duration.

*

The relationship between baseball and time is so fascinating. “The only sport without a clock,” as the old timer broadcasts like to say over the radio. Which is true, but also a bit of an illusion, since the majority of games end within 10-15 minutes of one another.

To be honest, most games last about three-and-a-half hours. Which, to many, seems interminable! Soccer and basketball are around two hours each, whereas football is, in my best estimation, about 14 hours per half.

But going back to baseball: sixty three-and-a-half hour games produces 210 hours of entertainment—for just your team. Thanks to the way the schedule is arranged, if you really wanted to, you could watch three games a day, which, including your team’s off days, could conceivable add up to watching 735 hours of live baseball over the next two months. That’s seventy-three ten-episode Netflix shows. A ton of content.

But also exceedingly finite.

Even when we look at a full, “regular” season, the perceived endlessness of the baseball season is quickly codified into very specific, countable numbers. In a normal summer, barring injury, you know that “your guys” will get about 620+ at bats over the course of these six months (that’s one hundred and three times a month you could watch or hear your favorite player bat, or, roughly 3.5 times a day).

That might seem like a lot—if you’re counting COVID sheep, you definitely don’t want to get to 620—but still, spread out like that over six months, it feels like Trout is rarely actually batting. Maybe he’s at the dish for 10-12 minutes a night. Again, extremely finite.

And by the end of the summer, your average star will have accumulated 130-150 hits, maybe 30 homeruns, a handful (or couple dozen) steals. Numbers that are remarkable in how pedestrian they are. For as long as any given game might seem—or, in the aggregate, the an endless summer’s worth of baseball—I can count to one hundred and fifty. That’s not that many times that a player was successful. Hell, I can probably even count to 150 over the course of a single at bat!

*

In these times though, that’s merely scratching the surface of what sorts of illusions can be incorporated into broadcast experiences. For the NBA, a limited number of fans will be able to buy “tickets” to a Microsoft Teams “Together mode” hangout, in which the fans can converse with one another, and be seen by players and fans watching at home.

Going back to baseball, FOX has decided to use Unreal Engine (the most Baudrillard name possible) to generate an imaginary crowd for its broadcasts.

Putting aside the more high tech approaches to simulating normality, let’s focus just on MLB crowd noise again. Because the MLB The Show crowd noise is a relatively uniform and non-descript murmur, the illusion will always fall short of verisimilitude. The viewer will never hear a drunken attendee accidentally scream nonsense next to a hot broadcast microphone. Fans will be cheated from hearing that one sole voice from from the bleachers who yells, “YOU’RE A BUM!” at the exact moment in which the rest of the crowd is relatively silent. The individuality that makes up the game’s attendees has been stripped from the broadcast. The same people don’t attend every night, but viewers of games this summer will hear the same general thing on every broadcast.

To combat this very specific “tell” that it’s all an illusion, Tom Hanks has given the Oakland A’s a soundtrack to use of him playing a stadium vendor.

In the recording that is being incorporated into to the game broadcast, Hanks is heard yelling phrases like “Scorecards, programs, yearbook! Can’t tell the players without a program!” and “Peanuts! Bag of peanuts! Two bagger, two bag o’ peanuts!” And, of course, there’s “Who wants a hot dog?”

Hanks’ voice will be mixed with crowd noise so the faux vendor can sell food to the cardboard fan cutouts in the stands.

*

The large image accompanying this post is copyrighted by Retis.

Leave a Reply