Anatomy. Monotony. [Reading the Dalkey Archive]

Anatomy. Monotony.

Edy Poppy

Original Publication: 2005

Original Publication in English Translation: 2018

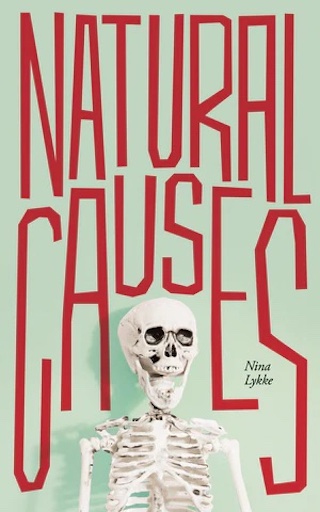

Original Publisher in English: Dalkey Archive Press

Although I’m filing this as a “Reading the Dalkey Archive” post, it’s actually about two books: Anatomy. Monotony. by Norwegian author Edy Poppy, translated by May-Brit Akerholt, and Natural Causes by Norwegian author Nina Lykke, translated by B. L. Crook.

And no, I’m not putting these two books together simply because they’re both by female Norwegian authors; I’m putting them in conversation because they’re both about extramarital affairs, the quest for romantic freedom and satisfaction, and jealousy. The two novels explore two different approaches—an open marriage, a secret affair—to the dissatisfaction, or incompleteness, so often found in traditional relationships.

They also present two different types of monotony. In Poppy’s book, the repetitive nature of the couple’s open relationship—taking a lover, returning to one’s “primary” partner, cutting things off, starting again—becomes repetitive. Poppy states this much more eloquently in her conversation with Siri Hustvedt (read the whole conversation here):

I had sent them an early version of the novel, then called: Speculations About What Once Was, But That I Can Now Only Remember. In return I got a big analysis of my work and a refusal. One criticism was regarding the marriage of my main protagonists, a Norwegian wannabe writer called Vår and her French husband and mentor Lou. It was that the couple’s constant love experimentation was resulting in an unexpected form of monotony. Of repetition. And even though it was meant negatively, I thought, well, that’s very interesting; I want to explore that more, not less! I understood many things about my writing through this rejection.

In Natural Causes, the monotony is of the narrator Elin’s life and marriage. She’s a general practitioner whose patients tend do the same things over and over again. (Sometimes dangerous, such as continuing to smoke and drink, never to diet. Other times not so dangerous, but just as annoying, such as the hypochondriac who never stops coming in hoping for a diagnosis.) And her relationship with her husband, who is obsessed only with participating in skiing competitions, is a total monotonous drag.

There’s an affinity between these two books, a shared urge between the two female protagonists to find the best way to keep going, to live a life that’s fulfilling in a way that feels deserved and right.

*

But let’s back up and take these one at a time.

Anatomy. Monotony. is the story of Vår who, like any good protagonist in a Dalkey book, is struggling to write a book about her relationship with her husband. She’s married to Lou, but early on in their marriage was encouraged by him to maintain an incredibly passionate, almost obsessive relationship with a painter. (He’s referred to as “The Painter” in the excerpts from the novel she’s writing, and referred to as “The Lover” in the “real life” sections of the novel. I’ll use “The Lover” from here on out.)

A thruple, in modern parlance, and one that works . . . sort of . . . for a time. Lou encourages her to pose for, be painted by, and make love to The Lover; and Vår is caught between the love and desire she has for her husband and the freedom he allows, and the near animalistic passion she experiences only with The Lover.

But then, jealousy. And things end with The Lover.

“The Lover and I . . . We could never get enough. It was on the border of cannibalism . . . I really loved him, I truly did, I almost sacrificed Lou. But then it turned out to be wrong after all. Because now it’s over. Now I feel something else, less painful, safer . . . Friendship.”

The Lover remains a constant in the background, throughout the rest of the novel, sometimes as the friend Vår wants to talk with late at night, the love she hasn’t really “gotten over” (one of the best lines in the book is “nostalgia doesn’t mean anything other than what used to be is over, and now you wish it could be again”), and as an experiment that maybe went too far—at least for Lou. Which is why he proposes a sort of game, a chance to do it all over again, to find a similar type of freedom, but that this time he’ll be able to handle himself, to deal with the jealousy, to do things right.

Of course, in the present time in the book, Lou has gotten quite involved with Sidney, a young girl who resembles Jane Birkin (R.I.P.), and with whom he takes lots of long walks, pines over, randomly spends nights with, so on and so forth. Which makes Vår jealous.

In her words: “Jealousy is something I have nothing but contempt for, but it still gnaws away inside me. I refuse to be broken.”

So Lou makes a proposal. With a sort of Nietzschean logic he tells Vår that if she falls in love with someone again, like she did with The Lover, he’ll leave Sidney for good.

Enter The American. A cello player (his cello being the “only woman I’ve never left, and who has never left me,” a line so cheesy that Lou’s mocking groan slightly vindicates him) who lives in Amsterdam, has written a composition called “The Sexual Life of Plants” (another groan) that he’s about to debut, and with whom Vår has an instant, intense connection.

I don’t want to recount this book beat for beat—and to be honest, I’m cherry-picking moments here to try and logically build a sordid situation, whereas the book itself is muddier in a delightful, emotional way with semi-erotic digressions and meditations, and lots of other details rounding out these characters and their love affairs—but I wanted to get to this point, because this is where the masculine jealousy really starts to kick in.

Jealousy is always bad. And masculine jealousy is toxic and frequently dangerous.

Edy Poppy

If what I’ve written so far has you at all interested, you really should read this book for yourself. If you’ve ever felt love for multiple people at once, regret a relationship from the past that went sour or ended, or simply entertained the possibility of a nontraditional arrangement (“I never dreamed of finding the man of my life. I wanted to be independent. Free. Feminist. Lou, on the other hand, always dreamed about finding the woman of his life, even if he didn’t dream that this woman would be me. He wanted to be dependent. Macho. But it didn’t turn out like that.”), this book will raise a lot of questions and bring to light a lot of complicated feelings.

There’s also a pervasive sense of male creep throughout this novel, which the book undermines without being didactic or strident. Occasionally Poppy will be direct and on point, like in this passage:

“I mean that you should go to Amsterdam, Vår, that you should see, smell, feel, and let yourself be ‘fertilized’ . . .” says Lou and mocks me with the American’s cliché. “That you should take a chance. And if it goes to hell, if it goes the way I want it to . . . then I’ll take you back.” [Emphasis mine.]

But oftentimes the creep is just lurking, there in the background, in the form of phone calls and questions, and a latent desire to control the narrative . . . which all leads to a surprise (in part because it is not physically violent) resolution.

*

By contrast with Vår, Elin in Natural Causes has always lived within the bounds of what’s deemed “acceptable.” From the way she deals with her patients (who all test the bounds of her patience in different ways, each expecting the world, a quick and easy solution, without consideration for anyone or anything else), to her cozy life with her husband in a totally pleasant suburban community.

By contrast with Vår, Elin in Natural Causes has always lived within the bounds of what’s deemed “acceptable.” From the way she deals with her patients (who all test the bounds of her patience in different ways, each expecting the world, a quick and easy solution, without consideration for anyone or anything else), to her cozy life with her husband in a totally pleasant suburban community.

It’s not that she’s “buttoned down,” rather that that’s just the way things are. You work hard, earn a decent salary, live a comfortable life, and enjoy (maybe too much) drinking wine.

And then, almost by accident, she messages her former boyfriend—the one before her husband, the one with jealousy issues—and her life swerves.

At the start of Lykke’s novel, a year has passed since Elin sent that initial message, and a lot has happened. Most notably, Elin’s been having an affair with Bjørn, and more notably, her husband just found out. And unlike Lou from Anatomy. Monotony., he’s not about to entertain the possibility of any sort of “open” relationship.

What follows are essentially two plotlines: one recounting the development of the affair with Bjørn, the joy and freedom and hope and peace it brings to Elin’s life, the other a micro-analysis of her day at the clinic and all the stresses and impossible requests the average person makes of doctors and science in today’s day and age.

These intersect and bounce off one another, and equally held my interest, but for the sake of this particular piece, the affair is the only one I really want to write about.

In this instance, the jealousy displayed isn’t necessarily as tinged with destructiveness—or at least that isn’t the primary focus when it comes to Aksel, Elin’s husband—instead it plays as a sort of selfish narcissism, an inability on her husband’s part to understand Elin’s needs and desires. (“Aksel might have wanted the same thing that I did, that we would get over this crisis and grow from it and keep the home fire and the hearth fire and the daily fire burning, but none of that helped as long as other parts of him did not agree. And since these other parts of him were the parts that determined the basic functions, he was unable to sleep as long as I was next to him in the bed.”) And that’s just as hurtful, and just as disappointing. Especially since Elin sees the vibrancy gained through her relationship with Bjørn as a potential positive for her relationship with her husband.

And yet, quite clearly, and with my full consciousness, I noticed how quickly the normal, ordinary version of myself was replaced by this being who must have been asleep inside of me, and who behaved contrary to all of the things I’d said and believed up to that point.

Early on I began thinking in this way: What if I can take this energy and joy which I’ve found, all of this secretiveness and excitement, everything that’s welling up inside me, and which makes me have less desire for drinking wine and watching TV and everything else that I used to chew and drink and swallow in order to soothe and calm myself—what if this could give me and Aksel a new life?

By applying a kind of controlled and intelligently designed alchemy, the illegal would become legal, the dirty would become pure, and the painful would transform into something edifying. The end would sanctify the means, and all of this goodness, this wonderfulness, the delectable, the forbidden, would be permitted to go on and on and on, for eternity.

Nina Lykke

I’m not going to use this (very small) platform to promote cheating on your spouse, or necessarily embracing an open relationship—which isn’t for everyone, and can be tricky even for those who are into it—but it’s not unusual to reach a certain age and, despite the quality of your relationships, feel like there might be something more. Not necessarily a Grand Love Affair, or a Passion for the Ages, but a connection that is invigorating. Life is simultaneously very short and very long, and confining a person’s ability to love and experience—especially the way men have traditionally restricted their wives—feels so small and petty and limited.

And although neither of these books offer any direct solution to this age-old issue, they both wrestle with the complexities and paradoxes of love and freedom in ways that will definitely resonate with a wide swathe of readers—male and female, jealous or supportive.

*

To return to Anatomy. Monotony. for one second, with that idea of complexity and paradox in mind, it’s worth thinking about the way in which Vår is writing what is essentially autofiction inside of Poppy’s novel that, well, reads like autofiction.

The book is dedicated to: “my husband, who has given me everything, even what I didn’t want. (He is now my ex-husband).”

And ends with the Fresán-esque disclaimer: “P.S.: Everything I’ve written is true apart from what I’ve invented.”

Finally, there’s this quote from Vår that’s right at the heart of desire’s contradictions: “I answer that to miss me is wrong. That to miss me is the same as wasting time. A lot. If he can’t forget me. I close my eyes and I suppose that deep down, that’s what I hope. That I’m unforgettable.”

Leave a Reply