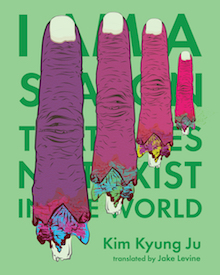

“I Am a Season That Does Not Exist in the World” by Kim Kyung-Ju

I Am a Season That Does Not Exist in the World by Kim Kyung-Ju

translated from the Korean by Jake Levine

144 pgs. | pb |9781939568144 | $14.95

Black Ocean

Reviewed by Jacob Rogers

Kim Kyung Ju’s I Am a Season That Does Not Exist in the World, translated from the Korean by Jake Levine, is a wonderful absurdist poetry collection. It’s a mix of verse and prose poems, or even poems in the forms of plays, all of which make use of what could most simply be termed an overriding sense of “synesthesia.” Throughout the collection, Kyung Ju mixes up sensorial language, whether that which we use to describe our bodies, or the world around us. What results is a fascinating defamiliarization and confusion of the way we use language to describe our lives, what we feel and experience, in a fever-dreamlike onslaught of vivid, visceral images.

Not simply interesting for their absurdity, these moments of confusion are also so well-rendered that they still feel somehow realistic and tangible. Jake Levine’s skillful translation of the collection must have been monstrously difficult, as it’s bursting at the seams with wordplay, assonance, consonance, and rhyme, with sumptuous, gorgeous language as fascinating for its absurdity as for its clarity. On top of the sensory confusion, Kyung Ju also weaves in a mix-up of the way we describe various forms of art: tactile or olfactory words for music, auditory words for painting, and so on.

In fact, one of the collection’s recurring themes is that of music as an allegory for human life. To cite just one: “In my previous life I was not human. I was music . . . Beethoven didn’t compose music. Beethoven was music. What he recorded was only his desperation.” In evoking one of the most famous classical composers, the suggestion seems to be that there is transcendent beauty to be found in the sublimation of our experiences, emotions, and sensations into art, blurring the lines between where the art and person begin and end.

He further clarifies and expands upon the synesthesia in the collection with a third layer. Not just a mixing of senses, or of the senses related to art, he also blends the art forms themselves. Though the collection contains a large amount of prose-poems (another kind of line-blurring), the true moments of confusion come with poems like, “The Moment After the Rain Hits, We Hug a Rainbow and Enter a Hotel with an Old Bathub.” Beginning as a poem, it moves on to Act I, II, and III—the first two still in verse, and the last of which takes the form an absurd dialogue between “Man” and “Kim” (ostensibly Kim Kyung Ju himself). It is a short, confusing back and forth where Kim wonders if Man is his son, and the issue is never clarified, but ends with Man carrying Kim on his back, pretending to be a plane, as if reversing the possible father-son connection.

Child-parent bonds, too, are an important theme in the collection, with countless references to “Mom” and “Dad.” In fact, the often shadowy presence of Mom may even contain the root to the work’s absurdity. In some rare moments, she shows up as a tragic figure in his life: “Mom, please stop dribbling . . . Turning on your side, purple bedsores pop;” she is dying before his eyes. These moments are often surrounded by language that juxtaposes absence and presence, as well as confusing, contradictory, or nonsensical sentences. On top of being paradoxical, there’s a sense of avoidance when he says “like a love for mom that never existed, my sorrow begins,” like a child shaking its head no at something to make it untrue, like the speaker wanting to negate the love in order to avoid the pain. However, in the collection’s penultimate poem, “A City of Sadness,” over ten pages long, the speaker rambles on and on about music and life and poetry only to end, finally, with a surreal scene:

the people that were entering the water that were carrying the coffin all had the same face as my own . . . But then, I wondered, in the coffin whose body was laid? I ran and ripped away the flowers covering the coffin . . . There, laid to rest, was my mom . . . Instead of her head, my head rest in the arms of my decapitated mother’s corpse. My face had my mother’s smile.”

With this fever-dreamlike ending, Kyung Ju finally takes a deep dive into the sorrow surrounding the sickness and death of the speaker’s mother, illuminating all the anxiety, confusion, and absurdity of such an event.

The subsequent, chaotic search for meaning, understandings of oneself, of the world, of art, are jumbled up, resulting in a language as absurd as the thought of losing one’s mother: a language parallel to and yet divorced from reality as we know it. This collection seeks new language, new ways to signify art and life out of the tumult, sublimating absurdity itself in its effort to explore this new language. That this language is so beautiful, so vivid, so familiar and familial, despite all its apparent absurdity, is a testament to both Kyung Ju’s skill as a writer and Levine’s light-footed, wonderful translation. What results is a readable, tragicomically absurd text that’s worth countless re-readings.

Leave a Reply