Seventeen [Why This Book Should Win]

Check in daily for new Why This Book Should Win posts covering all thirty-five titles longlisted for the 2019 Best Translated Book Awards.

Adam Hetherington is a reader and a BTBA judge.

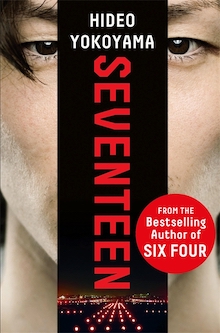

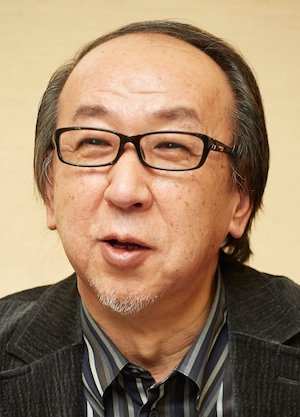

Seventeen by Hideo Yokoyama, translated from the Japanese by Louise Heal Kawai (Japan, FSG)

In August of 1985, Japan Airlines (JAL) Flight 123 crashed into Mt. Osutaka in the Gunma Prefecture, killing 520 people. Hideo Yokoyama’s Seventeen recounts this tragedy from a unique perspective, as the author was employed at the local newspaper—the North Kanto Times (or NKT)—at that time. From the preface:

At the time, I was working as an investigative/police beat reporter at a local Gunma newspaper. I arrived at the crash site after trekking for more than eight hours up a mountain with no routes or climbing trails. The terrain was steep, unimaginably narrow, and it was the rare lucky reporter who didn’t inadvertently step on a corpse.

Yokoyama, an investigative reporter and an amateur climber, was dispatched up the mountain to the crash site, while his character Kazumasa Yuuki manages the coverage from the office. It’s impossible to know which aspects of the novel are lifted verbatim from Yokoyama’s experience and which are fiction, but the distance of the character Yuuki’s position from Yokoyama’s own leaves room for a further type of reportage: a device to cleanly separate an individual character from the intertwining of the known personal and larger, newsworthy histories.

This type of disentanglement of the individual pieces of a book played a part in Six Four, Hideo Yokoyama’s only other novel available in English (translated by Jonathan Lloyd-Davies), too. It used the lure of an unsolved crime to examine the structure of Japan’s police. It was sold as a crime thriller, and while it did technically contain all the spinning gears generally associated with thrillers, it was not particularly thrilling. The book moved slowly, accumulating a mass of detail through something like the interrogation of the procedural genre itself. You could maybe call it meta-procedural, or a deconstructed thriller, though both of these terms seem to imply a level of formal experimentation that isn’t really present. Its differentiation from most other crime novels is Yokoyama’s un-exploitative realism. Thrillers often work through exaggeration—characters are reducible to one thing: genius, evil, dumb, funny, crass, sexy, etc; coincidences are numerous and fortuitous; the lives inside the plot are all moving toward something recognizable and tidy, not so different from episodic crime TV shows. Yokoyama’s fiction works though the incremental recreation of life. Indirect, branching, stalling, lovely life. Rather than a cat-and-mouse game of clues, we get a character map of action and empathy over time, revealed through the repeated sounding-out of the overlapping bureaucratic silences that make up the structure of the police itself. Six Four is a moving, beautiful novel, largely consisting of things almost happening.

In his book Sculpting in Time (translated by Kitty Hunter-Blair), Andrei Tarkovsky wrote “The aim of art is to prepare a person for death.” Yokoyama’s Seventeen, translated by Louise Heal Kawai, somewhat reverses this. The events surrounding the investigation into the crash that caused 520 deaths prepare Yuuki for the beauty available in his own life. He is a flawed, frustrating protagonist: quick to anger, fairly self-aware without any drive for self-improvement, and introspective without ever applying any of what he discovers about himself to daily existence. When we meet him, he’s simply aware of the conditions of his life, and of the conditions his sometimes horrible actions cause in the lives of others. He is sinking into his own existence, avoiding change or growth. But later, Yuuki—outwardly stoic in complacency, inwardly clear-eyed about his shortcomings—finds a type of personal success in the newspaper’s investigation in an unexpected way. Despite himself, he is able to withstand the absolute crush of capitalism on the news. Yuuki stands up to everyone. He demands integrity from a bureaucracy, and somehow he gets it, though at great personal cost. Through the competing pressures of a life realized through an investigation, Yokoyama again shows us the organizational structure of a job, and of its place in Japanese society. This is his brilliance, I think; his ability to describe one knot while untangling another. I actually didn’t plan on writing about what the book is so much as what it does, and I think in doing so, I’ve undersold something: how emotional it is, and how bare it left me. It’s a very careful book, almost understated, and it’s about a circumspect person, but it’s not at all cold. Yuuki transcends what he thought he could do professionally, which is who he thought he was personally, which then in turn slightly changes who he is as a person. I don’t want to overstate Yuuki’s redemption or transformation, but some things do change for him, and through this, that un-exploitave realism I mentioned earlier becomes emotionally animate. With the steady, measured prose of Yokoyama and Heal Kawai serving as scaffolding, Yuuki’s growth and personal interactions begin to resonate like the advent of technicolor; the landscape of his purposefully flat life begins to pile and erode. I don’t want to give any specifics here (apologies for pitching you half a plot in this post; I don’t really care about giving spoilers generally, but I do worry that in this case the bell might ring a little less true if you expect to hear it), but the book has a kind of plain honesty that put me in mind of John Williams’s Stoner, though that’s all they have in common. The judges for this award have had a group text going since last summer, and while I’m not going to tip any hands except my own, I will tell you I’m not the only person who admitted to crying more than once while reading this book. Seventeen is a marvel.

In his book Sculpting in Time (translated by Kitty Hunter-Blair), Andrei Tarkovsky wrote “The aim of art is to prepare a person for death.” Yokoyama’s Seventeen, translated by Louise Heal Kawai, somewhat reverses this. The events surrounding the investigation into the crash that caused 520 deaths prepare Yuuki for the beauty available in his own life. He is a flawed, frustrating protagonist: quick to anger, fairly self-aware without any drive for self-improvement, and introspective without ever applying any of what he discovers about himself to daily existence. When we meet him, he’s simply aware of the conditions of his life, and of the conditions his sometimes horrible actions cause in the lives of others. He is sinking into his own existence, avoiding change or growth. But later, Yuuki—outwardly stoic in complacency, inwardly clear-eyed about his shortcomings—finds a type of personal success in the newspaper’s investigation in an unexpected way. Despite himself, he is able to withstand the absolute crush of capitalism on the news. Yuuki stands up to everyone. He demands integrity from a bureaucracy, and somehow he gets it, though at great personal cost. Through the competing pressures of a life realized through an investigation, Yokoyama again shows us the organizational structure of a job, and of its place in Japanese society. This is his brilliance, I think; his ability to describe one knot while untangling another. I actually didn’t plan on writing about what the book is so much as what it does, and I think in doing so, I’ve undersold something: how emotional it is, and how bare it left me. It’s a very careful book, almost understated, and it’s about a circumspect person, but it’s not at all cold. Yuuki transcends what he thought he could do professionally, which is who he thought he was personally, which then in turn slightly changes who he is as a person. I don’t want to overstate Yuuki’s redemption or transformation, but some things do change for him, and through this, that un-exploitave realism I mentioned earlier becomes emotionally animate. With the steady, measured prose of Yokoyama and Heal Kawai serving as scaffolding, Yuuki’s growth and personal interactions begin to resonate like the advent of technicolor; the landscape of his purposefully flat life begins to pile and erode. I don’t want to give any specifics here (apologies for pitching you half a plot in this post; I don’t really care about giving spoilers generally, but I do worry that in this case the bell might ring a little less true if you expect to hear it), but the book has a kind of plain honesty that put me in mind of John Williams’s Stoner, though that’s all they have in common. The judges for this award have had a group text going since last summer, and while I’m not going to tip any hands except my own, I will tell you I’m not the only person who admitted to crying more than once while reading this book. Seventeen is a marvel.

This is a great novel about a newspaper, and it was released in English in 2018. This alone gives it weight. When I sat down to write this, I was actually planning on writing this whole post about how Seventeen is an indictment of our 24 hour news cycle. This was not Yokoyama’s intent (Death of the Author and all that) at all, though the repudiation is total. His constant interrogation of fact, of the motive for gathering that fact, and of both the cost of and motive for sharing that fact feels like the polar opposite of what we have today. In Seventeen there’s still a struggle against the influence of profit on news, a ghost we’ve almost given up here in the United States. We’ve all lost friends and family to things like Fox, to news that exists as a profitable business model, first and foremost, selling the pyramid scheme of itself to people who should have known better. To being sold the idea that a person is right to live in fear, and because they’re absolutely right to be scared, their hatred of what they fear is both moral and intellectual; to right-wing journalists who are making a goddamn mint reinforcing this, telling people that what they’re already doing (being noisy about their willful ignorance) is right, and that unlike everyone else in history, they don’t need any introspection or change, or to apologize for anything, ever—they just need to keep tuning in; and to an entire religion that has been warped beyond belief, to allow its adherents to believe that because they are Christian, all the things they say and do are Good, and so it’s actually perfectly fine when they made the least Christlike man I’ve ever heard of president, still no cause for introspection or alarm; and to the cult of defending the president, a uniquely stupid, cruel man, who was born rich and doesn’t believe in anything, and who has never really worked: he’s never dug a hole, never cleaned a toilet, never counted down a till, never sold a book, never read an entire book, never loaded a dishwasher, never swung a hammer, never swept or mopped, never needed a paycheck on Friday. This kind of stuff is not in the book, but you can imagine how a novel about a newspaper doing the right thing could drag this out of a person. I’ll stop.

This is a great novel about a newspaper, and it was released in English in 2018. This alone gives it weight. When I sat down to write this, I was actually planning on writing this whole post about how Seventeen is an indictment of our 24 hour news cycle. This was not Yokoyama’s intent (Death of the Author and all that) at all, though the repudiation is total. His constant interrogation of fact, of the motive for gathering that fact, and of both the cost of and motive for sharing that fact feels like the polar opposite of what we have today. In Seventeen there’s still a struggle against the influence of profit on news, a ghost we’ve almost given up here in the United States. We’ve all lost friends and family to things like Fox, to news that exists as a profitable business model, first and foremost, selling the pyramid scheme of itself to people who should have known better. To being sold the idea that a person is right to live in fear, and because they’re absolutely right to be scared, their hatred of what they fear is both moral and intellectual; to right-wing journalists who are making a goddamn mint reinforcing this, telling people that what they’re already doing (being noisy about their willful ignorance) is right, and that unlike everyone else in history, they don’t need any introspection or change, or to apologize for anything, ever—they just need to keep tuning in; and to an entire religion that has been warped beyond belief, to allow its adherents to believe that because they are Christian, all the things they say and do are Good, and so it’s actually perfectly fine when they made the least Christlike man I’ve ever heard of president, still no cause for introspection or alarm; and to the cult of defending the president, a uniquely stupid, cruel man, who was born rich and doesn’t believe in anything, and who has never really worked: he’s never dug a hole, never cleaned a toilet, never counted down a till, never sold a book, never read an entire book, never loaded a dishwasher, never swung a hammer, never swept or mopped, never needed a paycheck on Friday. This kind of stuff is not in the book, but you can imagine how a novel about a newspaper doing the right thing could drag this out of a person. I’ll stop.

Finally, Seventeen is a book about the effect of the application of integrity—a thing available to all— to a life, and that gives me hope, which is as good a reason as any for a book to win.

Leave a Reply