Season 18 of the Two Month Review: Ann Quin Is the Missing Link

Before we get into this post, I just wanted to congratulate Annie Ernaux and all of her publishers and translators on winning the 2022 Nobel Prize for Literature. She’s a legend, and I have a special place in my heart for Cleaned Out, since that was a Dalkey book. (And the first of hers I read.) And also want to send a shout out to Fitzcarraldo/Jacques Testard, whose authors seem to win the Nobel almost every year. Kudos to all! And now on to this unrelated post.

For a year after graduation from Michigan State—while I was waiting for my then future wife (aka, No. 1 X-wife?) to complete her degree—I did nothing but read for the English GRE and explore all the books that I had been dying to get to, but never had time for when I was in school. I devoured every Pynchon book, Coover (The Public Burning in particular), William Gaddis, Wittgenstein, every Kathy Acker book, any and all pop-sci books about quantum mechanics and string theory, and some random academic books since, at the time, I had aspirations of going on to get a PhD. (Foolish Young Chad! Bad at love, bad at career choices!)

One of the academic books I really liked at the time was Fiction in the Quantum Universe by Susan Strehle. (Two great obsessions—fiction and “quantum”—that taste great together?) There’s a chance I’m misremembering this (or applying quantum ideas, there’s a chance that I’m both right and wrong and no one will know the outcome until they observe Strehle “Schröedinger’s” Index), but it was there and then that I first came across the name “Ann Quin.”

In a book about Pynchon, Barthelme, Atwood, and the like, a reference to Quin feels likely, although I think she was mentioned in a toss-away comment, one of those classic, “another author who mines this vein of theoretical underpinnings is Ann Quin, an experimental British novelist from the 1960s, who isn’t well-known these days” sort of bits. As vague as the reference was—in Strehle’s book, or whatever actual book I’ve replaced with hers in my memory—I was INSTANTLY INTRIGUED.

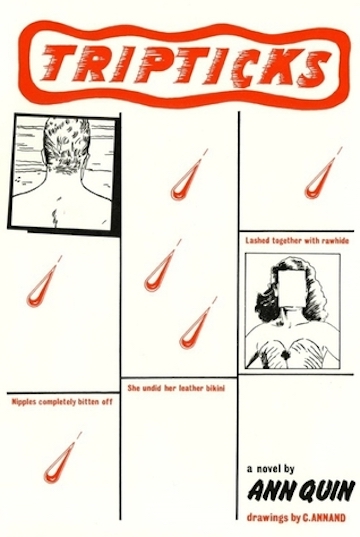

This took place in the way back, pre-Wikipedia, squarely in the dial-up era of the “information superhighway,” but I remember reading something about how Ann Quin could be considered a Kathy Acker precursor. Not a one-to-one comparison, but a fellow traveler on the experimental, NON-MALE, mode of storytelling. And that her “wildest” book was Tripticks, which included Goo-era Sonic Youth illustrations:

(All the illustrations in Tripticks are by Quin’s lover, Carol Annand.)

For whatever reason—that her books were really only issued in the UK by Marion Boyars Publishers, that online interlibrary loan requests were a few years in the future, that Amazon.com didn’t yet exist—I couldn’t get ahold of these books to save my life. Every new or used bookstore I entered I would pass by “P” for “Pynchon” and end up at “Q” for “Quindlen.” (I think Quindlen has lead a very successful life as a writer, but to me, she’ll forever be “the Q-named author who isn’t Ann Quin.”) This is a specific flavor of Nerd Disappointment some of you relate to. (And the rest of you make money with your actual hands and bodies like smart folk.)

Worth noting though that I did discover Raymond Queneau in this “Q”-related search.

[Side-note: If any QAnon people end up on here because I’m Q-ing it up like a Trump-liever, spread the fucking word! For every one of you nutjobs who contributes to our Patreon, we’ll find a Q-nugget in Quin’s books that presage your mysterious figure. Don’t worry: Quin’s poetic prose is dripping in potential conspiratorial clues. Tune in, weekly—and donate $5 a month—and we’ll enlighten you.]

[[Three Percenters? You, on the other hand, can go fuck right off. I’ve owned Google search results over you before, and I will again. Eat my words, “patriots.”]]

*

Fast-forward a few years, and I was starting out at Dalkey, recommending authors to reissue I had heard of, like, IDK, Ann Quin, and, lo and behold, John O’Brien pulls from his shelves all four of her novels. And thus a weekend is wasted.

Fast-forward a few years, and I was starting out at Dalkey, recommending authors to reissue I had heard of, like, IDK, Ann Quin, and, lo and behold, John O’Brien pulls from his shelves all four of her novels. And thus a weekend is wasted.

And a few conversations with Catheryn Kilgarriff later, Dalkey had put together a four-book project to reissue this unique author who, despite all her advances in the realm of what literature can do, she—much like her compatriot B.S. Johnson (a future TMR subject? I could talk for, conservatively, 7 hours about House Mother Normal and the statistics describing the current abilities of one’s senses: “Sight: 10%”), died way way too young of suicide in 1973.

RIP Experimental British Writing for a good couple of decades. (Or at least the best chance it had of going “mainstream.”)

*

It’s been twenty-one years since I read Ann Quin.

Since that time, And Other Stories capitalized on Dalkey’s negligence (aka, a monomaniacally-run dictatorship of a press whose empire was slowly crumbling) and started reissuing her—along with a collection of previously unpublished stories and fragments entilted, The Unmapped Country after her unfinished final novel—Bob Buckeye has written a critical book, Re: Quin, the literary world has caught up to the spirit behind her works, if not the specific structures and twists of language and grammar, and she’s even been featured in the New Yorker.

*

But what do Ann Quin’s works mean today? Can a contemporary writer draw from her, from her poetic play, her constant urge to expand and explore and truly experiment? How do readers relate to, in Danielle Dutton’s words, the author who “turned On the Road on its head”?

Well, if you listen along, you’re about to find out.

*

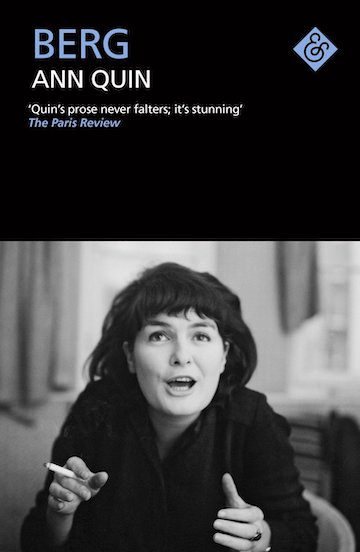

Ann Quin—originally published in the 1960s and early 1970s, then again in 2001-2003, and now in 2018-2022—is the subject of the next season of the Two Month Review. We’re going to include a record-setting five books in this season: Berg, Three, Passages, Tripticks, The Unmapped Country. All are available from And Other Stories, Bookshop.org, hopefully your local indie, Amazon.com, most libraries, the Dark Web, etc.

Ann Quin—originally published in the 1960s and early 1970s, then again in 2001-2003, and now in 2018-2022—is the subject of the next season of the Two Month Review. We’re going to include a record-setting five books in this season: Berg, Three, Passages, Tripticks, The Unmapped Country. All are available from And Other Stories, Bookshop.org, hopefully your local indie, Amazon.com, most libraries, the Dark Web, etc.

Not sold? Here are the opening lines from her novels:

A man called Berg, who changed his name to Greb, came to a seaside town intending to kill his father. . . .

[. . .]

A man fell to his death from a sixth-floor window of Peskett House, an office-block in Sellway Square today.

He was a messenger employed by a soap manufacturing firm.

[. . .]

Not that I’ve dismissed the possibility my brother is dead.

[. . .]

I have many names. Many faces.

So many men dying!!!! How can you not want to buy and read all these?

*

Well, if you’re still not sold, here’s a bit from Dutton’s New Yorker piece specifically about Tripticks:

Tripticks chronicles a nameless narrator’s exploits as he drives across America pursuing his “No. 1 X-wife and her schoolboy gigolo”—or else the ex and her lover are pursuing him. Let’s just say that they’re following each other, perpetually, in Buicks and Chevrolets, back and forth across a dystopian U.S.A. The America that we find in Quin’s novel is a place of rampant consumerism, religious hypocrisy, gory violence, and New Age self-help bullshit. It’s also sex-mad, drug-addled, racist, and riddled with the language of advertising clichés. When we do glimpse the natural environment out a car or motel window, it is often almost terrifyingly beautiful, a not quite surreal prehistoric vastness of mesas and rock formations, “sheer walls of symmetrical blue grey basaltic columns” and “salt pools with crystals forming on their surfaces” and “bare broken peaks.” But any romance of the American West is always immediately cut through, chopped down, and pressed up against something else, like “6 packs of fridged beer” and a “U-Drive Inn,” or a “lead-filled baseball bat” and a “hanging tree.” Of course, the setting of any novel, no matter how experimental, is made out of nothing but words, but that truism feels somehow truer of “Tripticks.” Language is the landscape that we’re traversing in this book, a shifting vista of TV commercials, political rhetoric, sexual fantasy, and sand dunes. Language is what’s happening in here.

*

In addition to Re: Quin, Amongst Those Left: The British Experimental Novel 1940–1980 by Francis Booth, a scholarly book that’s a who’s who of great mid-century writers, includes a significant piece on Quin and all of her works, and, thanks to the efforts of the And Other Stories, there’s a solid number of recent academic pieces and reviews of her books for us to consider throughout the course of the season. Which, I truly believe, is going to be so fun.

In addition to Re: Quin, Amongst Those Left: The British Experimental Novel 1940–1980 by Francis Booth, a scholarly book that’s a who’s who of great mid-century writers, includes a significant piece on Quin and all of her works, and, thanks to the efforts of the And Other Stories, there’s a solid number of recent academic pieces and reviews of her books for us to consider throughout the course of the season. Which, I truly believe, is going to be so fun.

As in the past, we’ll be releasing special interviews first on Patreon for subscribers (no, this venture isn’t funded, and exists mostly because of my unwillingness to let it die, so please, a couple bucks a month?) and in the podcasts the following Friday. If you want to watch us LIVE AND UNEDITED tune into our YouTube channel on the days below. And follow TMR on Twitter for more specifics and random stuff.

Let’s blow apart the male narrative model together!

October 26: Introduction

November 2: Berg (pgs. 1-82)

November 9; Berg (pgs. 83-END)

November 16: Three (pgs. 1-75)

November 23: Three (pgs. 76-END)

November 30: Passages (pgs. 1-56)

December 7: Passages (pgs. 57-END)

December 14: Tripticks (pgs. 1-103)

December 21: Tripticks (pgs. 104-END)

December 28: Unmapped Country (ALL)

Get your copies now, and get ready! And if you like what we’ve done in the past, please consider supporting us through our Patreon.

Leave a Reply