Ryder [Reading the Dalkey Archive]

Ryder

Djuna Barnes

Original Publication: 1928

Original Publisher: Boni & Liveright

First Dalkey Archive Edition: 1990

This is a baggy novel of excess, and as someone who finds it nearly impossible to keep the thread—or develop a coherent thesis (any and all AI grading systems would plant my writings firmly in the C to C+ range)—and who, by natural gift, or curse, likes to overstuff every post with footnotes and asides and self-references, I’m willing to bet that this appreciation of Barnes’s playfully polyamorous novel of Wendall Ryder, his mother Sophia, his wife Amelia, his lover Kate (aka Kate-Careless), and all their myriad kids, isn’t going to follow from point A to Z, but instead follow a more natural path of observation and exclamation, admiration and exhalation, repetition and repetition, all with the singular (maybe I can stick to something?) goal of convincing anyone who braves these paragraphs to read this book, or, if nothing else, at least skip-around in it.[1]

I’m convinced that Djuna Barnes is about to have her (overdue and deserved) renaissance.

By sheer coincidence (and laws about public domain), not only is Dalkey reissuing Ryder in a splashy new “Essentials Edition” this summer—with a new printing of Ladies Almanack coming early next year—but New York Review Books Classics is bringing out a Collected Stories in 2024 (?—as I write this, I can’t find a proper listing), with an introduction by Mervé Emre.[2]

And thus, the pieces are in place and the stage is set. But Barnes’s lasting appeal goes far beyond business machinations of the marketplace. She was a singular writer, with an approach and style so many readers of today will likely delight in discovering. The Lispector rediscovery comes to mind, although, on a stylistic level, Barnes is frequently compared to Nathalie Sarraute, another author ripe for rediscovery—and another Dalkey author.

Barnes is primarily known for her 1936 masterpiece, Nightwood, which is published in paperback by New Directions, and in a different, hardcover, version by Dalkey Archive, and is probably the only one of her books regularly taught in college classes across the U.S. And yet! She was a pioneer, perfect for the academy. A Rabelaisian writer, who, in the words of Paul West—whose afterword deserves to be read by all and sundry—“wanted to undo all readers, to deflower them in one way or another, to stop them from expecting fiction to behave like some well-bred social organism.” He goes on in that same afterword to state:

Early, she discovered the principle of addictiveness, meaning that she could always add something to something else, not because the first something was inadequate but because the observing or defining mind required such elbowroom. Her writing delineates, often with mordant accuracy, but she bloats it too, just to tell us she is there, serving the cause of plenty. She is among those rare souls, the phrase-makers, to whom a phrase no one else could have dreamed up is more precious than whole sequences of action or talk. Her work is there to evince her own mind, and to overface ours. Sometimes you have to read her with tweezers, other times with a trowel and a scoop, especially when she has let someone loose in a soliloquy. I think she sometimes thought of the novel as the supremist form of soliloquy, which is to say the novel at its closest to poetry. She has a superb sense of rhythm, so much so that she hears the rhythm long before the words arrive and the rhythm brings the combinations into being. Her prose evokes Wendell’s longing for “an extra large English pudding with whacking diamond-shaped goblets of suet shot through.” Above all, she is the virtuoso of the sentence, the ability to make which kept her going to the age of ninety. She built with bricks when others trifled with straw. She remained intense. She attuned herself to the constant ambience of heroic voice. She was serious, critical, and terminal, like an illness.

*

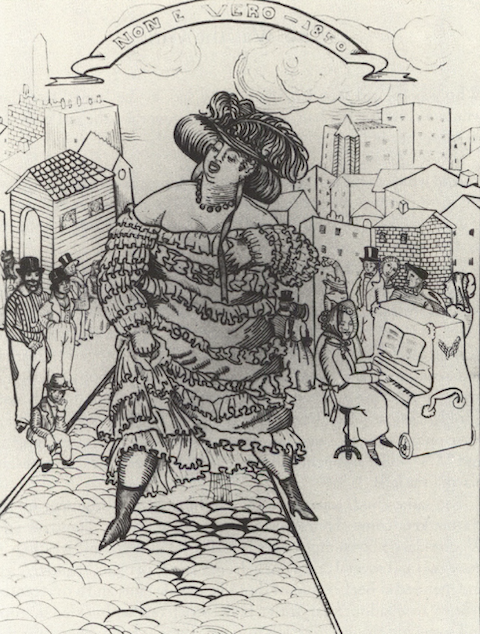

Djuna Barnes was born in 1892, and was a highly sought after journalist and illustrator—the Dalkey edition of Ryder includes almost two-dozen of these illustrations—who moved to Paris at the start of the 1920s (like some other American authors you may have heard of, who are taught in an array of English classes), and had a run of consecutive works—The Book of Repulsive Women (1915), A Book (1923), Ryder (1928), Ladies Almanack (1928), Nightwood (1936—the year of grand literary works), and The Antiphon (1958)—that’s almost unprecedented. (And, like West alludes to in his afterword, isn’t everything she left behind: she died at 90 and wrote for her whole life.)

The “plot” of Ryder—so much as there is one—is basically what I put in my opening ramble of a paragraph: It’s set around the turn of the nineteenth century, and features Sophia Grieve Ryder, a scandalous character who marries over and again, and breeds like her fore-mother (who had fourteen kids of her own), including by giving birth to one Wendall, the second of her sons, who, in England with his mother, meets Amelia, and eventually brings her back to America to be his wife. They wed. They start procreating. He immediately gets involved with Kate—who has her own non-traditional past of lovers and whatnot—and the three (four, counting Sophia) live together as separate from society as they can be (for not only is their bigamist/poly-situation a thing with the locals, but they don’t believe in sending their kids to school, which, again, pisses off the law-abiders), raising their eight (I believe that’s right) kids, having philosophical (and comic) conversations about love and life, squabbling with one another, roaming and repenting, and just making do.

It’s a great fable—a playbook if you will—for our troubled times. For the freedom-seekers looking for liberation and to transcend traditionally imposed, and most definitely male-centric, models of being.[3] Although incredibly complicated—no one’s relationship in this book is clean or “chill”—there’s a thread of outlaw joy from the deconstruction of societal assumptions that is both logical and a potential pathway to more open, human-to-human, relationships.

But putting aside the sociological import of the book and its desire to break free from everything—including expectations of what constitutes a “novel”—I want to focus on the fun, free-flowing frolic of Barnes’s prose, which, in every way, on every page, throws itself to the front of the stage, taking precedent over plot and “moral messages.”

*

This book cycles through styles like a postmodern Dreamachine, entrancing and dazzling the reader in a way that—maybe it’s our age, our attention spans, or maybe it always was this way—forces one to read and reread, to figure out how to parse the sentences, or, more accurately, how to hang on to the paragraph’s momentum, and, to throw out a reference point, although it predates Miss MacIntosh, My Darling by decades, there’s an affinity, a sort of roller-coaster vibe that rewards with every swerve, with every loop, every phrasing that feels anachronistic, or maybe stodgy? on the surface, but is just evidence of a high-wire act that’s almost inconceivable if you’re wedded (poly reference totally intended) to today’s dominant form or American neo-realism.

Let me try to explain.

But first, let me try and scare you off.

Or, rather, let me let Barnes simply show off. Here’s the opening of Chapter 1, “Jesus Mundane,” subtitled “By Way of Introduction,” which is wonderfully not for those who blush at unbridled ambitiously Biblical prose:

Go not with fanatics who see beyond thee and thine, and beyond the coming and the going of thee and thine, and yet beyond the ending thereof,—thy life and the lives that thou begettest, and the lives that shall spring from them, world without end,—for such need thee not, nor see thee, nor know thy lamenting, so confounded are they with thy damnation and the damnation of thy offspring, and the multiple damnation of those multitudes that shall be of thy race begotten, unto the number of fishes in thin waters, and unto the number of fishes in great waters. Alike are they distracted with thy salvation and the salvation of thy people. Go thou, then, to lesser men, who have for all things unfinished and uncertain, a great capacity, for these shall not repulse thee, thy physical body and thy temporal agony, thy weeping and thy laughing and thy lamenting. Thy rendezvous is not with the Last Station, but with small comforts, like to apples in the hand, and small cups quenching, and words that go neither here nor there, but traffic with the outer ear, and gossip at the gates of thy insufficient agony. [Boldface mine.]

First time through, that can be daunting. A clause-heavy opening sentence coming in at 102 words, which include three thee’s, two thy’s, and a begettest (!). Also, a lot of damnation. So much damnation. And a phrase set off by em-dashes that sounds like it’s coming right out of the mouth of a preacher: “Thy life and the lives that thou begettest, and the lives that shall spring from them, world without end” . . . You can almost hear the unwritten “Amen!”)

But, like every great book, it’s demonstrating how you can learn to read it, letting you in on what this book is all about.

Go not with fanatics who see beyond thee and thine, for such need thee not, confounded as they are with thy damnation and the damnation of thy offspring.

In short:

Hey, Wendall? Tell all those moralizing townies hating on your life, your wife, your mistress, and your kids to go fuck themselves! And don’t worry: those shit sippers aren’t actually paying attention to you: they’re all about ‘salvation.’ 🙄 Hang out with the riffraff.

Again, this is the backbone of the “plot” that a reader might like to know up front; off this clothesline hang tons of asides, set pieces, and musings that aren’t always “functional” in a strict “advance the plot” sense, but instead tend to be where the fun and frolicking is at.[4]

*

I’ll admit: Returning to Ryder almost a quarter decade after the first (and only) time I read it, one of my initial thoughts was, “oh, shit, this book is going to be difficult.”

Ryder is a novel that can be “difficult” to read because of the conflict between current patterns of speech and communicative gestures (texts, Instagram reels, emoji, directness), and the more baroque, labyrinthine way of articulating a journey instead of a message evidenced in every paragraph of the book, a style which tends to require such patient parsing. The reader has to attune themselves. And, frequently, be willing to release their grip on rules of concision and grammar (Struck & White can fuck themselves with those shit sipping townfolk of above) to allow a voice to lead them.

And sometimes, a literal voice helps.

(Recording done by Kaija Straumanis.)

It’s easy to read right past the pauses and emphases when you first visually encounter the opening paragraphs of this section:

It was a sweet spring morning, once upon a time, many, many, many years ago, when the two women, Amelia de Grier and Kate-Careless, went, as nature would have it (there being nothing new under the sun), upon their four feet to do up the dirty mess, and damn their infinitesimal-lime-squirting-never-stop-for-consideration-of-a woman cloacae (and she with the backache and the varicose veins climbing her legs), or whatever-you-call-the-backsides-of-a-pigeon, and to look into the matter of the eggs and casualties.

Up the dusty stairs they went, besoms in hand, a flower between Amelia’s teeth, and with stomachs crawling (for alas! there’s nothing new under the sun), into the thraldom of feathers, and there, strutting and cooing and bill-begging, round and round in a dance of death, went Blue-Wing and Sweet-Tuft, the metal rings on their twiggy ankles knocking out a convict’s tune against the imbrication of their feet, round and round in a merry pigeon lust, squirting trouble as they went, and smelling most hideous insufficient, as is the way with a bird.

Unlike the previous example, in which snapping off the grammatically key packets of information and lining them up eases a sense of understanding, this section works better if it’s performed. Read aloud, time distends in the paragraph, slowing down to allow the asides to land—asides that function almost like the motifs of a good stand-up comedy performance, something we’ll see a lot more of in a future installment in this series of posts when we get to Momus’s The Book of Jokes and Ben Slotky’s An Evening of Romantic Lovemaking—letting the reader/listener fall into the rhythms, finding an understanding of the paragraph’s intent in its delivery rather than its strict meaning.

For me, the irony comes through better when I hear it read than when I see it on the page.

*

I love this book. Every chapter, a journey. (Stay tuned to this spa

ce for a couple of longer excerpts closer to the time that this will be reissued.[5]) And more than the specific ideas, the

dismantling of traditional partnerships and expressions of sexuality (quick note: the book was censored when initially published in America[6]), it’s the way in which each chapter of Ryder asks new things of the reader—to cotton onto what style is being invoked, to enter into the jazz of the text—reading like a game in which all sides can win.

Again, and circling back to the beginning, it’s time for the Barnes-assance.

*

Oh! There are also drawings:

Which is as good a place to wrap this up as any given the images and design-heavy elements of Ladies Almanack that will inevitably be part of a future post. Till then, I’ll leave with one final line: “And whom should he disappoint?”

*

[1] In Macedonio Fernandez’s Museum of Eterna’s Novel (The First Good Novel), he writes about the “skip-around reader” who follows whims instead of page numbers, driving Macedonio to put his book together all out of order—so that the “skip-around reader” would chance into reading it in the order Macedonio actually intended.

[2] It should go without saying, but if you want actual insight and literary analysis into Barnes’s work, read Emre’s intro! (And/or the issue of the Review of Contemporary Fiction on her.) Not necessarily this piece.

[3] Although in our topsy-turvy world, this same basic situation could be, maybe, and I’m just riffing here, adopted by the libertarian right, those who want to live in partnerships (with both guns and the right to fiscally deceive other people) without too much local (government) oversight, “parents’ rights” when it comes to education?

This may be a book about the paradoxes of morality and the people who attempt to enforce it, but this probably isn’t the place to point out that the “hands off my ____” thread of extreme conservatism should really, more than almost any other object or idea, be applied to books, words, and their general access. This also isn’t the time or space to mention the obvious dissonance between wanting to use all the so called “non-Woke,” “offensive” words, yet not want the opposite—the “Woke,” and to-a-fault “non-offensive” ones to exist alongside. These are not brilliant observations, just expressing a desire for honest shithousery in modern discourse: If you’re gonna be shitty, at least be honest about being shitty.

[4] “‘Nicknames,’ said Wendell, ‘give away the whole drama of man. They fall into many classes; the three most current are: those we invent to make a person what he should be—or names of persuasion; those we invent to make him appear as he is not—or names of cunning, and those we invent to more tightly wrap him in that which he is, and these are as various as our opinion of the person involved. Let us call them nicknames o f opinion. Take my own case,’ he continued, ‘for philosophy, like charity, should begin at home. Let us tell then, the story of your mother’s first reactions to your humble servant, and we shall have a case in hand. It will instruct you in the nicest turns and twists of such games, for and against, that you can think of, to say nothing of the abundant humours therein involved. It will be more to the point,’ he added, ‘than whole dissertations on nature, and will round out the inevitable end as you know it.

‘During this soliloquy, heed well what she does, and what she does not call me, for therein lies the whole mad obscurity of the female heart. Observe where she might have mocked and did not, where again she might have placated and forbore, how, again, she might have had me swollen with pride, and spake not the word. Indeed, she might have said a number of things—but, enough!’

[5] I have at least two chapters that I’m dying to share. Hang tight.

[6] From Barnes’s foreword: “This book, owing to censorship, which has a vogue in America as indiscriminate as all such enforcements of law must be, has been expurgated. [. . .] Hithertofore the public has been offered literature only after it was no longer literature. Or so murdered and so discreetly bound in linens that those regarding it have seldom, if ever, been aware, or discovered, that that which they took for an original was indeed a reconstruction.”

Leave a Reply