‘I Also Saw the Women Who Came Before Me’

‘I Also Saw the Women Who Came Before Me’

Ileah Welch ’05

A child advocacy lawyer is selected for a prominent portrait series that’s earning wide praise for its depiction of black Americans.

Ileah Welch ’05 and former First Lady Michelle Obama have something in common: both have had portraits painted by Amy Sherald, an artist who’s earning national recognition for helping bring the lives of black Americans to prominence in American art.

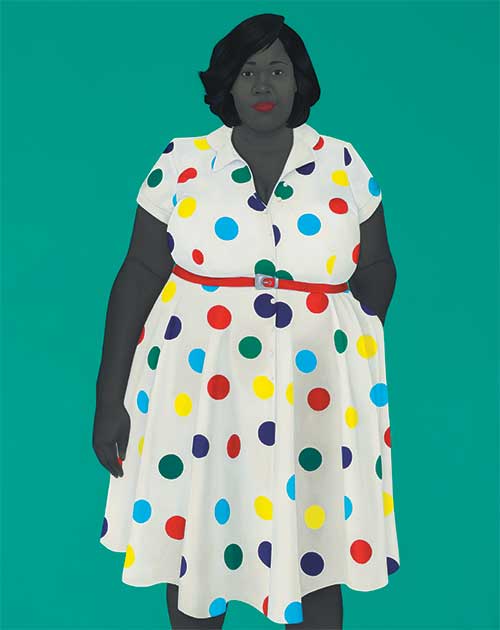

ART MAJOR: Welch, the subject of one of seven paintings in Sherald’s highly regarded 2019 exhibition, says the artist’s work captures the experience of African Americans in ways that are rare in major art shows. AMY SHERALD, THE GIRL NEXT DOOR, 2019; OIL ON CANVAS (137.2 X 109.2 X 6.4 CM 54 X 43 X 2 1/2 INCHES) © AMY SHERALD; COURTESY OF THE ARTIST AND HAUSER & WIRTH

Just two years after unveiling her portrait of Obama—a work that’s now in the collection of the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, DC,—Sherald mounted a solo exhibition last fall at Hauser & Wirth, an influential New York City gallery. Titled At the Heart of the Matter . . . , the suite of paintings featured portraits of African Americans.

One of the paintings was of Welch, who says the paintings are particularly moving because they beautifully and simply capture ordinary aspects of daily life for African Americans and the black community. That experience, she says, isn’t often represented in major art exhibitions.

“When I walked in, I saw the painting immediately. It took my breath away,” Welch says. “Amy highlighted the equally important parts of me, and she gave meaning to the small things in the painting, like the lipstick, my hand in my pocket, and the polka dots on the dress.”

Opening last fall, the exhibition was acclaimed for showcasing Sherald’s “smoldering yet self-contained brand of portraiture,” as a review in the New York Times described the exhibition.

Capturing her subjects’ faces in a gray monochrome—a grisaille that the artist has made her signature—Sherald places her subjects in bold settings and vibrant backdrops, resulting in paintings of confident people who “invite close, exclusive looking, a kind of communion.”

Several reviewers cited the exhibition as one of the most important of 2019. For Welch, an anthropology major at Rochester and now a child advocacy lawyer in Washington, DC, it was an unexpected honor to be painted by Sherald.

“I saw the portrait of me,” she says. “But I also saw my mother, my sisters, and the women who came before me—and you know her, too.”

The story begins in the summer of 2018, when a friend sent Welch a screenshot of an Instagram post. An unnamed artist was holding a casting call in Baltimore that day and was looking for black models of all sizes and shapes, between the ages of 8 and 80. On a whim, Welch and her sister, who was visiting from out of town, headed to the studio.

The artist turned out to be Sherald, and in January 2019, Welch heard from the artist’s studio manager, who said Sherald wanted to paint Welch’s portrait. To fill in more of the back story: the manager later said Sherald had never used an open call to recruit models before. She didn’t like the process and doesn’t plan to do it again.

In the end, the only person Sherald chose to paint from all the people who responded to the call was Welch, who was invited back to Baltimore for a full photo shoot with Sherald. “That’s how Amy works. She takes a million photos and then she paints from them,” Welch says, remembering how nervous she was at the photo shoot. “I’m not a model and I don’t know what it’s like to ‘smile with my eyes’ or to ‘look serious’ for the camera. But Amy was great—so friendly and welcoming—and she made it easy.”

While Welch eventually found out that Sherald had completed a portrait of her, she didn’t know whether it would be in the New York exhibition until she walked into the gallery last fall. The work, a portrait titled “The Girl Next Door,” drew the eyes of reviewers as well, who found in it a companionable self-possession that drew them to wonder about the young woman’s life beyond the frame.

As the New Yorker noted: “Her look is rather guileless—far from the cool savoir of the beach people—but equal, you somehow know, to whatever daily life she is leading. She is praised by Sherald’s brush for the insouciance of her garb: the bouncy dots a tonic exception to the refinement of the abstract designs that the other subjects’ clothes provide for this painter’s aesthetic use. “What’s the neighbor’s name? I’d like to know. I almost feel that I do—on the tip of my tongue, about to come to me.”

“That’s what I felt,” Welch says, as she reflects on the ways the portraits resonate beyond a single viewing. “I saw the portrait of me,” she says. “But I also saw my mother, my sisters, and the women who came before me—and you know her, too.”

— Kristine Thompson

This article originally appeared in the winter 2020 issue of Rochester Review magazine.